This piece comes to us courtesy of The Hechinger Report.

A new spirit of reform pervades Quitman Street Community School in Newark, N.J. In recent decades, school and city alike have been beaten down and subject to wave after wave of so-called rebirths, renewals and reforms. The Hechinger Report has partnered with NJ Public Radio and NJ Spotlight to share Quitman’s story over the next year, dispatching a team of reporters to cover its daily trials and triumphs and the lessons it provides for schools and communities nationwide.

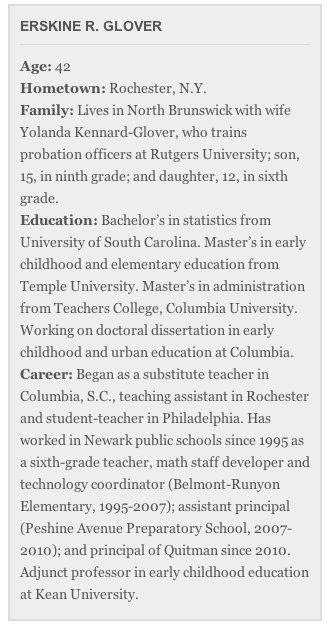

NEWARK, N.J.—Erskine Glover has interviewed for his job as principal of Quitman Street Community School three times in the past two years—undergoing a total of 15 hours of questioning. With his latest rehiring a few weeks ago, he was given authority to decide which of his teachers will return for another year with him.

Glover believes weeding out subpar instruction is the single most important action he can take to lift Quitman out of New Jersey's academic doldrums. But the anxiety for staff waiting to find out by Friday, June 15th, if they are coming back only adds to the school's challenges and distractions in the waning days of this academic year.

Walking the halls last week, Glover was infuriated to find one teacher sitting at the computer while students did as they pleased. At a planning session with colleagues, another teacher slammed her hands down on a table in frustration, then stepped out to catch her breath.

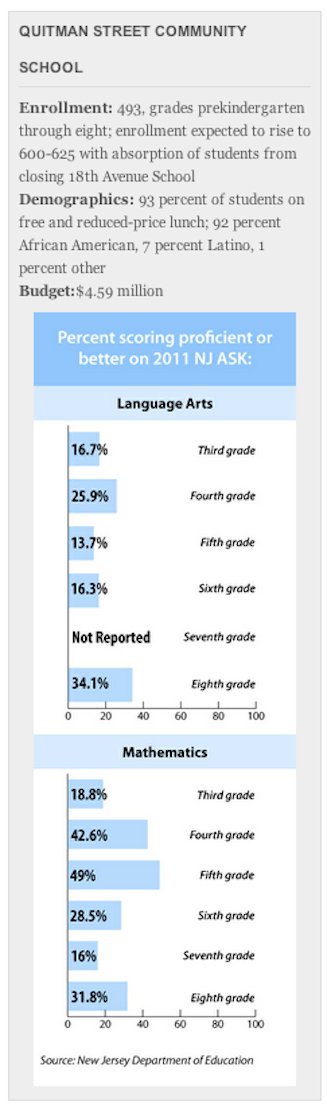

Quitman—a school of 493 pre-kindergartners through eighth-graders in Newark's high-crime, high-poverty Central Ward—has become a symbol of Superintendent Cami Anderson's new push to turn around the city's struggling schools by closing down the worst of them and replacing staff at others. At the same time, the school has become a target of a new statewide reform effort that calls for selective staff replacement, a strategy the Obama administration is prescribing for the lowest-performing schools around the country.

Glover is trying to be humane about his impending decisions, communicating with teachers as he gets information from the district and scheduling individual meetings so people don't learn their fates via form letter. But he is simultaneously relieved to have the power to make changes and worried that he won't be able to go far enough if the district doesn't allow him to make outside hires.

"We can't ignore history. This has been a low-performing school, and we have done something wrong collectively in order to get to this point," Glover said. "That makes all of us held accountable … So if it means reorganizing the staff, that's what it means."

Rebecca Mays, a prekindergarten teacher who is retiring this year, estimates she's seen a dozen principals since her arrival in 1987. Every two years, it seems, there's been a new curriculum. Mays can't help but wonder how this time will be different, but she is glad Glover will be returning.

"Things aren't going to change overnight," Mays said. "You have to give people a chance to tell if something works."

After all the false starts and dashed hopes, will this really be Quitman's turning point?

The prospect has Glover, 42, cautiously optimistic. As a boy growing up in Rochester, N.Y., he saw anything less than an A in school as unacceptable. On the basketball court, he could practice longer, stronger, harder to boost his chances of victory. Before coming to work in public education in Newark, Glover didn't know losing, and he doesn't like losing.

Yet here he is leading a school that time and again has been labeled a loser, and no matter how many hours he works and how prepared he is, some things have been beyond his ability to change. Now he's getting to make changes—with more discretion over his budget, as well as over staffing—but he's still waiting for answers to critical questions, especially about whether he can hire from outside the district.

"I'm excited," he said, "if I'm going to be able to really be the leader that I know I can be."

Glover's leadership will be subject to a lot of scrutiny in the coming year. Anderson is looking for dramatic gains at Quitman and seven other "renewal schools" that will be absorbing students from six schools she's shutting down. "When you're stuck at 21 percent proficiency, incremental growth is just not going to get us where we need to go without losing a generation of kids," Anderson said.

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie wants results from the 258 schools he's targeted for extra state help; Quitman is one of 75 in the group labeled "priority." Quitman is also one of seven schools in the Newark Global Village School Zone, modeled after the Harlem Children's Zone in New York City, which links education and social services.

Under the auspices of New York University, Global Village is funding everything from an extended school day at Quitman to student eyeglasses to teacher and administrator training. It, too, provides watchful eyes over Glover.

But Glover's toughest evaluation is the one he's giving himself. What would success look like to him?

"Minimum, minimum 85 percent of my students being excellent learners where they could compete with any student in the state of New Jersey and in America, where my school is ranked one of the best in the country," he said from a conference table in what he's turned into Quitman's war room for data analysis. The skill comes naturally to him given his undergraduate major in statistics, but is less natural to much of his staff.

"It does not mean we pass [state tests] and we're proficient," Glover said. "That's a very low bar for me."

Yet last year, Quitman's highest pass rate on the annual New Jersey Assessment of Skills and Knowledge, known as NJ ASK, was 49 percent in fifth-grade math. Its lowest was in fifth-grade language arts, 13.7 percent. A third of students or fewer demonstrated proficiency in eight of 12 tested areas. Scores weren't even reported in seventh-grade language arts, where the teacher was on leave almost the entire year.

In Glover's view, an intangible institutional complacency among staff is at the heart of Quitman's troubles, a focus on ritual compliance rather than student outcomes. Have students been working? Yes. Learning? Not necessarily. He is investing heavily in teacher training and collaboration. Teachers interviewed said they're doing the best they can with children who arrive with major academic deficits in one of the poorest neighborhoods in one of America's poorest big cities.

As Glover makes decisions about who stays and who goes, he has had to ask tough questions of them.

"Education is no longer about, ‘I have a job, I'm at a school and I'll stay there 25 years,' " he said. "It's really about, ‘Am I the best fit for the location I'm in?' "

He asks his teachers, "Do you really want to stay at Quitman, or do you want a job? There's a difference."

One May afternoon on Quitman's stuffy third floor, a dozen seventh-grade boys in royal blue polo shirts and khaki pants trickle into their English class over a 15-minute period, alternately slamming the door behind them and leaving again to use the bathroom. (Glover has divided the middle grades into single-gender classes, dubbed "kings" and "queens.")

One boy comes in playfully hitting another; the teacher kicks them out. The students are working on the same assignments as the eighth-grade boys were the prior period: finishing opinion essays on school dress codes, "I Am" poems and color poems. (One boy's musings on green: Collard greens on a plate / String beans that I never ate / Spinach that I'll never take / Green soda going down your throat.)

The teacher, who is also getting ready to retire after a quarter-century there, says it's hard to keep students' attention at the end of the day, especially with lunch at 10:30 am.

One boy puts his head down on his desk, proclaiming himself finished. Another complains to the teacher: "I already did this, but I didn't give it to you."

"If you didn't give it to me, you didn't do it," she replies.

The boy who says he's done gets up and leaves. "See y'all at gym," he says on the way out.

A boy in the back row walks over to a bookshelf, picks up an autobiography by the puppeteer behind the Muppet Elmo, returns to his desk and starts reading. Another boy who isn't doing anything begins to tease him.

One in the front of the room is singing. One in the middle who has been trying to work complains about all the door-slamming. He puts down his pen and goes to talk to a friend working on a computer at the back of the room. The screen shuffles between a grammar assignment ("Which sentence uses correct capitalization?") and NBA standings.

At 2:05 p.m., the boys charge swiftly out the door, passing a desk where a stack of "I Am" essays from the last class is sitting.

On top is this one: I am tall and smart / … I worry sometimes I won't make it / … I understand life is hard / I say man is wrong about everything / I dream (of) becoming BIG / I try to do good at all times / I hope life doesn't end / I am tall and smart.

***

In evaluating a historically low-performing school, it's easy to assume that everything needs changing. At Quitman, that would be a faulty assumption. Start with the physical appearance of the building, kept immaculately clean. It was constructed in 1963, which is practically new by Newark public school standards, even if the absence of air conditioning does present breathing difficulties for students with asthma.

Haydee Gonzalez, a tiny graying woman who teaches Spanish, took it upon herself a few years back to paint every last inch of hallway, and proved herself a remarkable artist. A palate of magenta, orange, turquoise, yellow, purple and other bright hues provides the backdrop for the walls, which Gonzalez then brought to life with Disney and Dr. Seuss characters and illustrated nursery rhymes in the preschool wing. Her favorite display is the Hawaiian vacation scene she did on the second floor. Under the title "Read Baby Read," she painted six kids and a dog on a beach blanket hovering around a book titled Hawaii, a lobster, starfish and dolphin in the water beneath them. A parrot nearby is repeating, "Read, read baby."

The security guards at the school's entrance as well as the secretaries in the front office offer warm, welcoming smiles, which aren't always easy to come by in a so-called failing school. A medical clinic is on the premises, the PTA is small but growing and very active, and students can choose among several extracurricular offerings, including an in-school television news network. New townhouses from Newark's redevelopment efforts line the streets surrounding the school.

"Before you wouldn't be able to walk across the street from Quitman," said Stephanie Ruff, the school's parent liaison and a native of the neighborhood. Quitman does still draw from some of Newark's toughest housing projects, where Ruff and the school social worker have been known to pound on doors at 9 p.m. to track down parents. Every day they round up kids out of uniform and drag them home to get changed.

Quitman has high attendance rates, and major disciplinary incidents are rare. Many urban public schools face a lot of teacher turnover, but not this one. Teacher turnover is perhaps too low in Glover's opinion; he believes every staff needs a mix of stability with an infusion of new energy and ideas.

A married African-American man at a school where 92 percent of students are African American, 93 percent qualify as low-income and many don't have dads at home, Glover knows some kids see in him a father figure. He tries to set an example, starting with his style of dress. At 6-foot-3, he wears flashy suits that typically involve a matching bowtie and vest or handkerchief, with his long dreadlocks neatly pulled back.

"For my students, I need them to see that being a well-groomed man, being a well-groomed individual, doesn't mean you have sold out, doesn't mean that you're not in tune with the urban trends," he said.

Glover sets a standard for staff in punctuality, accessibility and professional development. Despite what are often 13-hour days at school, he is enrolled in a doctoral program at Teachers College, Columbia University, in New York City, at work on a dissertation about the use of technology in math instruction for African-American males. On Tuesday nights, he teaches early childhood education as an adjunct instructor at Kean University in Union, N.J.

He doesn't see many of his teachers working as hard as he does. He estimates that only a quarter would have the drive to work in a "no-excuses" charter school where they'd be expected to be available for families around the clock.

"They have the baggage and the teaching styles of a Newark Public Schools teacher," he said. "And what does that mean? You're under a union; you can get off at 3:05. You operate as if, ‘Well, I'm still gonna get my contract once I get tenure, so if my students don't do well…' "

Newark Teachers Union President Joseph Del Grosso said the principal is responsible when that type of mentality arises. "The principal is supposed to be the leader of the building and should create a certain morale," he said. "People don't have any reservation about blaming the teacher … When teachers fail, the principal failed."

Joyce Faller, a Quitman reading teacher for grades 1-3 and a union representative, said teachers are trying, but each year children show up with less developed academic skills. The high-performing charters that Glover admires, such as North Star Academy a mile and a half away, can send students back to their neighborhood schools when they don't do well. "We can't do that," Faller said.

Mays, the retiring prekindergarten teacher, believes one of Quitman's biggest challenges is the stigma attached to the school. "Once you get a name and a reputation, it's hard to shake it," she said. "The children want to learn. We've seen children go on to college and military. There's been some success stories here."

Glover, who rose through the ranks of public education from humble beginnings as a teacher's aide and substitute, was once a union rep himself. As one of only two college graduates in his entire extended family, his motivation is deeply personal. His own son and daughter attend more successful public schools in North Brunswick where they don't have any trouble with the basic-skills tests that bedevil the children at Quitman.

Passion for his students' welfare has carried Glover through his three job interviews and some rocky terrain during his first two years at Quitman.

The first interview was in 2010 with Clifford Janey, who named Glover principal in one of his final acts before his ouster as Newark's superintendent.

Replacing Janey, Anderson promptly placed Quitman on a potential closure list. The struggle to save it proved a mammoth distraction for the rest of the academic year. Parents and community members mobilized—but over survival rather than academic support—and some staff worried more about their jobs than the quality of their school. In giving Quitman another chance, Anderson re-interviewed and rehired Glover.

This year, Quitman is caught in a battle between the Newark Teachers Union and the district over impending staff changes. Tenured teachers are legally entitled to a position somewhere in the district and can still collect their salaries if the district doesn't place them. A bill in the state legislature would allow the district to eventually dismiss those who aren't placed, but even if it passes, many technicalities are at play, and the union is poised for a showdown.

"The tenured teacher has a right to a position under the law, and we will enforce that part of the law," said Del Grosso, the union president. He said decisions are being made "based on whether a principal likes you or dislikes you."

As principal of a renewal school, Glover had to re-interview for his job yet again this spring. He and the other renewal school principals got only four weeks to assemble their staffs after their own hiring or rehiring on May 17th. Although Glover will be held personally accountable for the school's performance each year, Anderson said she expects it to take time for him to assemble a dream team.

"Over the course of the next couple years, I think he will have the authority and time and empowerment to get the team he needs," she said. "I don't think it is either reasonable or achievable to think that can be done in four weeks."

The district will evaluate its budget and resources after June 15th, the deadline for principals to extend offers to current Newark teachers. Glover worries about the prospect of having to fill openings with teachers who weren't placed elsewhere rather than hiring from the outside.

"I'm really fearful," he said, "if we have to bring back disgruntled staff members."

***

If Erskine Glover could rule his world, he would freeze all his middle-school students at their current grade level until he could instill in them a sense of urgency and responsibility for their work. Even more than any academic deficits, a work ethic is the critical component he sees lacking in students who have grown up with a string of long-term substitutes and a history of low expectations.

Of Quitman's 47 eighth-graders, Glover estimates that only seven are truly prepared for high school, and another 28 could be with the right summer school program. Many read on grade level, most don't skip school, and only one or two have significant behavioral issues, he said. But they have yet to learn the importance of working hard. Glover said he hates—hates—social promotion, but is unable to require more than a handful of students in each grade to repeat the year without getting bogged down in legal challenges that would only derail his efforts.

Glover convenes the entire school in its combined cafeteria-auditorium each morning at 8:25 to set his expectations for both students and staff. On the morning of May 10th, he asks for an update on a reading competition where the boy and the girl in each grade who read the most books that month will win a "monetary award" (a Barnes & Noble gift card).

"How many students so far this month [among] eighth-grade girls have read five books, THIS MONTH?" he says into a microphone. "Stand up. I want to see who's in the lead." A few girls stand.

"Alright, come up to the front." He goes through each grade. "Sixth-grade girls … This month, not the whole year. I'm only on the month of May. Fifth grade, who's your highest reader?"

By third grade, 15 students are standing in the front. "And second." A few dozen little ones run up.

"So," Glover says, "I'm gonna honestly say that I don't believe you, and you have to prove it to me." He calls up the school librarian, responsible for overseeing the project, and reminds her of the poster-size chart he requested to track the competition publicly. He asks for the highest number of books students have read so far. Only the second-graders have documented reading more than five books in the first 10 days of May.

"So let's try this again," he says. "You talk, I talk—that's a problem. That's adults and students … I'll wait, 'cause even adults aren't ready … If there's 31 days in this month, theoretically … you could read at least 31 books … Zero is not acceptable for readers who want to become leaders. Are we clear?"

The room is quiet.

"Are we clear?!"

"Yes!!!!"

"Alright."

Among younger children, Glover's aim is to train parents to demand academic excellence. The issue isn't that they aren't involved, he said, "but I think that parents look at safety first: ‘Is the school safe? Will my child have a good teacher in front of them who protects the child's safety and well being?' And we sometimes forego—parents, and then teachers sometimes fall into this—the educational aspect."

Last month, after children's author Mary Pope Osborne donated copies of her 28-book Magic Tree House series to every third-grader in Newark, Glover threw a catered luncheon for third-grade parents to promote summer reading. It was held in the "cafetorium," where staff and students built a giant tree house out of cardboard and construction paper.

Olivia Benders, a hairdresser, appreciated the efforts on behalf of her son. "The last principal wasn't as excited for the kids," she said. Her older child transferred from Quitman to a charter school a few years ago, but she'll be bringing him back next year.

Lawrence Polen, a dad sitting two tables over with his third-grade boy, said he's noticed a big cultural improvement at Quitman in recent years. "Back when my other son was going here, it was more a streetwise school, [with] trouble bullying," he said. "Now they don't tolerate that here."

His other son also attends a charter now, North Star Academy. Asked how the two schools compare, Polen seemed taken aback, as if it were a silly question. "North Star is a tough school," he said. "It's more of a challenge."

The luncheon came on the same day as a newspaper article announcing Glover's reappointment as principal, and he used his time at the podium to address the issue.

"This is the third time in two years that I've had to reapply for the principalship of Quitman Street School, so there are many people who say it's destined for me to stay here," he said. "I don't know if they think I'm not competent, capable—I don't know. But what I believe is that there's a reason I'm here. I believe that if given two more years, this school will be one of those schools that people are knocking on the doors to get into."

Privately, Glover cites another factor he'll use to gauge his success. The reforms need to outlast him. He lists off organizations with success ingrained into their cultures regardless of who's in charge: IBM, Manchester United. It bothers him deeply that urban public schools in high-poverty neighborhoods don't have that.

"If Erskine Glover leaves in two and a half years and he's off to sitting on an island in Barbados and comes back five years later, will he still be excited about what he sees?" he asked. "If not, Erskine Glover failed."