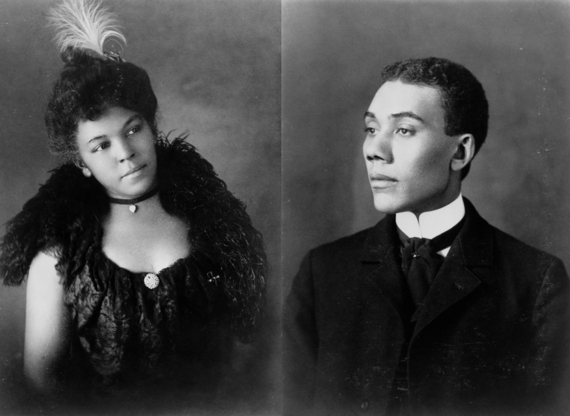

"The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line" wrote historian and sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois for the Exhibit of American Negroes in 1900, Paris Exposition. Du Bois compiled three albums containing 363 black-and-white photographs, mostly of middle-class African Americans from Atlanta and other parts of Georgia. Du Bois's photographs were in contrast, to other turn-of-the-century images of criminal mugshots of African Americans, racist caricatures and lynching photographs. Du Bois's act of curating and presenting theses images was essential in deliberately challenging racist representations of African Americans. Describing the exhibit he wrote,

...an honest straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves. In a way this marks an era in the history of the Negroes of America.

A hundred and thirteen years later, visual representation created to militate against prejudice and racism remains relevant. "Stakes of representation and the fundamental connections between race, visual culture" and who controls visual culture remains contentious. Shawn Michelle Smith calls Dubois's Album a counter archive, that challenges the long history of racial taxonomy that offered competing visual evidence. Much of what follows is another archive of conversations about race, visual representation and our place in this discussion, with a new breed of photographers, writers and thought anarchists.

------

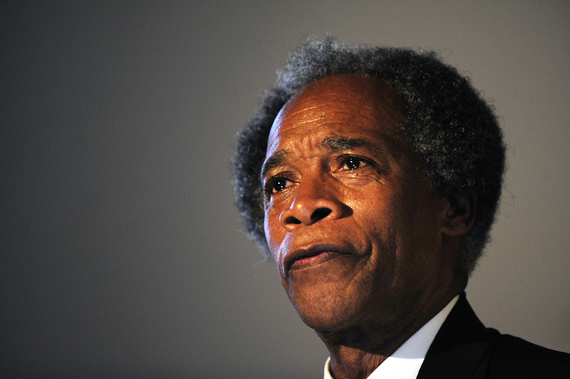

Conversation with Brent Lewis

It was October 2012 and I was at the very famed Eddie Adams workshop. It was here that I meet Brent Lewis. Brent's work was fresh and exciting. He was smart, intuitive, generous and real. In room full of up and comers wanting to list their accomplishments and aspirations, Brent was interested in you, he wanted to get to know you as a person.

We were both people of colour in a largely caucasian gathering, where the rhetoric of bearing witness to the atrocities borne by the "others", was still the dominant narrative. But something else happened over the weekend, that started our long standing conversation about race, visual representation and the future trajectories of photography. Brent was one of the two African students at the workshop, the other was the South African photographer, Mbulwana Lungelo. The Eddie Adams workshop ends with a presentation of student work and towards the end various prizes are given away. One of the prizes was a Nikon D4 with a nice little lens package. The South African photographer Mbulwana won it. As the event ended and the after party began, people started walking towards Brent and congratulating him, thinking he was Mbulwana. In Brent's own words,

I looked at them weird, because in a room full of caucasians, we were only a handful of minorities. I had to clarify that it wasn't me. They looked at me awkward for a second, then apologized and played nice real quick. By the 4th or 5th time this happened, I started getting slightly annoyed. Off course I was offended. First, we don't look anything alike. The Mbulwana was like 5.2 and I am 5.6. He was bald, and I had a full head of hair. He is African and I am African American. We spoke differently. I am slightly fat he was skinny. Physically and facially we looked nothing alike, except that we were both black. Over the course of the night seven different groups, that totaled to at least 25 to 30 folks came up and said the same thing.

The Conversation

Suchitra: In 1996 Guggenheim did a retrospective -- In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to Present, with 30 ethnically and racially diverse African photographers active on the continent who, "employ, critique and exploit notions of photographic truth concerning African representation." This was considered a landmark exhibition, the first of its kind in the U.S. I am wondering if today the Guggenheim was to put together something similar for African American Photographer, do you think they can come up with 50 names they can curate down to a 30 or so?

Brent: In the hay day, you could have gotten 50 African American Photographers. I can probably jot down a list from my memory. But in the recent years, the numbers are much lower. Today there are probably 20-25 African American photographer working in the field. The number goes down when you consider photojournalism and documentary approach. It is lower when you talk about the one's who are famous and it is single digits when you think about those who are still alive. When you talk about African American photographers, you immediately think of Gordon Parks. He is also the reason why I do, what I do. Another is Eli Reed, amazing photographer, who did this great work in the 70s and the 80s. Then John H White, one of the best newspaper photographers ever. But the name recognition stops there. If you think this is too low please reach out to me because I would love to meet more.

Suchitra: Let us double back. May be give context to your work. What made you get into Documentary Photography?

Brent: This almost feels like a cliche. But it was from my grandfather. He always had this big box camera. Sooner or later it was going to find its way into my hands. Once he gave me his camera and told me to take a picture. I took the picture, looked over and realized that it is a Hasselblad. My mind was blown. What was my grandfather doing with one of the greatest cameras in the world? Why did I not know anything about this till now? I started talking to him and found out that he used to do wedding photography in Chicago. He was probably one of the only African American Photographers with high-end gear doing this on the south side of the city.

I borrowed his gear and initially it was a hobby. I went back to school, I was at Northern Illinois University at that time. I heard they were hiring at the newspaper and thought it might be a 'cool', maybe I might make some beer money. Then I fell in love with it. When I decided this is what I wanted to do, I started doing research. Being African American, it was intuitive to immerse myself in the work of Gordon Parks. It struck a chord. He was telling "Our Story, My story ". After that I transferred and ran into John H White. John was doing the same thing. He was telling our stories, telling stories in a way people usually don't tell our stories. Or for that matter for most people of colour. The good, the bad, the ugly, the sweet, the kind... and that is something you don't see.

I lean towards my people. We are often represented as being poor, as if being poor is a quality. When I was in Chillicothe, Ohio, lots of African American's were middle class. It is nothing like Chicago. Every place is distinct. So I had to dive into the history of this place. Too many people are trying to tell our stories without understanding our stories, I feel it is like my duty to go out there and tell our story.

Suchitra: When you talk about "our stories", it makes intuitive sense to me. Sometimes what I see printed on a paper before me, does not reflect the realities of what I am experiencing...

Brent: Exactly...

Suchitra: So let me ask you in the reverse. What were the kind of stories, that did not make sense to you? Because when photographer's encounter differences, it is easy to sum them up with the most convenient terms at their disposal.

Brent: My grandparents were middle class. They educated two daughters sending them to college without student loans or getting into debt. My mother and aunt were sent to the best schools. It was not easy, but it was accomplished. I look at myself, I made it to 18 without getting shot, am not a "gangbanger". I didn't grow up in the Projects, though I was aware of that other life. Where was my story? It is not just living in the projects, selling drugs or the Black Panthers. Our lives were not a exposé. There is an image John White took in the projects. It has two kids running towards the camera smiling. These are uplifting images.

Ovie Carter, former Chicago Tribune photojournalist and Pulitzer winner, after seeing my work said, "You are missing the other side of the story." It was great to hear someone say that to me. He said what I was feeling. Some photos might get you a World Press or a Pulitzer but that is not telling the other half of the whole story. I rather tell the whole story and not be recognized for it, but when I pass away I can be happy that I told the stories that matter.

Suchitra: Multiplicity does poses a difficult hurdle because it carries with it a sense of instability that disrupts the foundations of preconceptions previously rendered immutable ...

Now moving on to the more "alarmist tendencies" within photojournalism. There are two things that go hand in hand. First what is the ubiquity of the photograph, with millions of images floating around. Second it is the question of being found or discovered amongst this noise and finally the capital required to create and disseminate this work..

Brent: Yes, the work is diluted and there is just too much. Then there is this attitude, "I am going to be the next big photojournalist, say cheese poor people" When it comes to publishing, with the shrinking editorial and magazine space, and millions of sites out there, It is easy to publish, but hard to be found. I can take a picture and publish it on instagram, but to be "seen" is the real problem. In this day and age, your work has to almost go viral, because it is eye catching or shocking. If not then it really doesn't get out there. Or if you have a large following on social media. Else you have to win a contest. Stories about middle income African American family is not going to be seen. It might get published. But without shock and awe it is not going to win a contest. This is the same with Kickstarter, at times it feels like a circle jerk, photographer funding photographer. It is also the triviality of the matter. A kickstarter doing 50 faces of royal baby will raise 20,000 without a problem. With serious stories, unless you are already famous or established, the wider public is not going to fund it. t is very very difficult to get work looked at, published and funded.

Suchitra: To what extent, do people see you, judge you differently. Today if you look at depictions of photographer in television, they all look like James Nachtwey

Brent: Ha ha ! They do.

Suchitra: James Stewart as a Life magazine photojournalist in Rear window, James Wood in Salvador, Fred Astaire, Jude Law, Bradley Cooper, Clint Eastwood and Patrick Wilson...

The representation of the photographer is still predominantly caucasian, male, intense, single, brooding and deeply wounded by something. Cloned versions of Nachtwey, with aging female editors still holding a candle for them. There is another kind of profiling as well, reverse profiling of someone who doesn't fit this profile. In this context then, how do people receive you ? What do you make of the post racial America argument? I can see you cringe, already ... so go on

Brent: Lets throw post racial America outside the window, please! It affects people daily. It's not as bad as it once was by any means, but it's still there. There are two stories I think that says a lot about the time we are in. First, I was working for the Redeye, a new bar was opening in Chicago and I was sent to do some details shot. I walk in and introduce myself. The manager comes in, takes a nice long look at me and says, "Oh I thought they were sending Brent". I had to clarify and confirm that I was indeed Brent. These situations happen a lot. Even here, in Southern Ohio, lot of the time people are shocked when they see a African American Photographer.

They see a black kid, then they see a black kid with a camera and finally they realize it is a black kid, with a camera working for a newspaper. When they see all three together they are shocked. "You work for the (Chillicothe) Gazette" and then it is followed by "oh, umm" and a surprised awkward "yeah !"

Suchitra: Chris Rock joked about it years ago, in regard to Colin Powell. Rock, said "Speak so well isn't a compliment. It is what you say about retarded people who can talk"!

Brent: Exactly. I guess I am still lucky, in that I came to work around the time when Obama being the President was a possibility. I did not have to fight the stigma of, "Oh you can put that lens together. Wait, wait you are wearing a belt ? I don't have to deal with that blatant, on the face racism, but I still have to deal with peoples expectation of what it means to be black.

I was shooting a White Sox game, two years ago. When taking a break, some of the field crew came over to talk me.

Hey man, who do you work for?

Chicago Tribune.

Man, I have been doing this for 3 or 4 seasons and I have never seen a black guy here doing what you are doing.

How was it possible that you have never seen a Black photographer doing what I am doing ? I have a reason to do this. I represent a branch of people. When I go somewhere, I represent them. They are not just a story. They know I care, because their story is my story. The light that they are cast on, gets cast on me. I have a responsibility. But I have come to accept that I will be looked at strange when I walk into an expensive restaurant to photograph it or when I walk into a CEO's office to photograph him. Of course I will.

Suchitra: I know you have this special relationship with John White. The more I have gotten to know you, I feel like you make an effort to be like him, emulate him...

Brent: John was the reason why I came to Columbia College. I grew up with his work, almost not knowing it was his work. Once you meet John you don't forget John. Just the soul he brings to everything he does, not just photography. It is John being John, his every essence of being. I strive to emulate him, I do, I have to. His passion for life, people and their story, you can't help but be captivated by it. If you get to hang out with John White, do it. Every young photographer should just do it at least once. He is just that cool

Suchitra: He offered to twist with us ..

Brent: Yeah he did... I want to be John, as a person. The way he thinks. Who he is. He won the Pulitzer for not covering the African American in the South Side of Chicago, or some war, it was covering Chicago and its remarkable people. Caring about that moment and passing it on to his readers. The care and love John puts into his work, is just remarkable. He doesn't make a story, hoping to win a Pulitzer some day ! He is there because he cares, thats what I want, and strive for daily. There are days that I wake up and don't want to work like everyone else Then is it always, what would John do ? The Passion he put into all of us, his students. To be in his presence, I hope he can spread it to another generation of kids, and them maybe we will have an industry that cares. Take the photo that matters. Keep in flight.

Brent Lewis is a photojournalist born and raised in Chicago Ill. His work has been published by the Chicago Tribune, Associated Press and most recently the Chillicothe Gazette in Chillicothe, Ohio. More of his work can be seen at www.blewisphoto.com