Two weeks ago, millions of people watched as 51 survivors - including myself and my fiancée- standing alongside Lady Gaga delivered an unforgettable performance of "Til it Happens to You," an original song from the campus rape documentary The Hunting Ground. Introducing the performance, Vice President Joe Biden made a powerful statement against victim blaming, inviting viewers to join him and student activists in pledging to change the culture surrounding campus sexual violence. The Hunting Ground was just made available for streaming on Netflix, so people who haven't yet had the opportunity to see the film- which screened on CNN last November and has been screened at over 1,000 colleges and universities in the last year- will be able to see it and learn more about the issue. I challenge anyone to watch the film, or Lady Gaga's performance, and not come away sharing the Vice President's belief that something, something needs to change.

So what is that something?

It's tempting- and perhaps just- when we hear about the rape epidemic on campuses to want to focus on finding and punishing the perpetrators. A bill proposed last fall, the so-called "Safe Campus Act"- sought to address this problem by instituting "mandatory reporting"- demanding that if survivors turn to their school for support, they must also go through with filing a formal report to the police. Dubbed the "(Un)Safe Campus Act" by activists, dialogue over the bill showed that focusing on prosecution and punishment rather than support and healing raises questions of believability and probability of conviction for all survivors, who are held up to the myth of the "perfect victim" and are often re-traumatized in the process.

A side effect is that this focus on prosecution and "justice" causes us to minimize the vast majority of rape and sexual assault cases that do not result in conviction and punishment of a "bad guy," asking survivors, "Well, did you report? Were they found guilty?" If not, doubt emerges. Legally, every perpetrator deserves due process. But every survivor deserves to be believed. The two are not in conflict if our response to hearing about rape does not require that we go out and find "the bad guy," but instead, that we support the survivor in their healing process. The truth is that "solutions" to domestic and sexual violence do not occur in a vacuum, and can cause more harm if they do not account for the real root causes of violence.

My professor once told a story about prevention that I think is applicable here. She said, "if you were standing next to a river, and saw someone in the water, drowning, you would help that person. But if another person, and another, and 10, then 100 more appeared, you would no longer be able to help them all. And after a while, you would ask why all these people were in the river, drowning. If you asked them, and they told you that someone just upstream was pushing them it, you'd solve the problem not by finding a way to rescue them all, but by stopping the person pushing them in."

How can we prevent rape, not just prosecute and punish those responsible? One policy change that has resulted from lobbying to address this issue is "Bystander Intervention" in which students are trained to intervene in situations that look "risky." This runs the risk of confirming stereotypes about what assault looks like, and ignores the fact that over 60-80% of rapes are committed by someone the victim knows- a friend, or a dating partner. Someone who doesn't look 'suspicious'- someone the victim trusts.

Many activists would point to Affirmative Consent legislation, which was signed into law by the California legislature in 2014 and is becoming the standard policy on many college campuses. Just like the White House's "It's On Us" campaign, affirmative consent and "Consent Education" inform students of a shifting standard from "no means no," to "yes means yes," which means "If you don't get affirmative and ongoing consent, it's rape." Sex is pretty complicated, though, and 'doing it' right- consensually, pleasurably- requires some pretty advanced communication and an understanding of issues from consent to anatomy, power dynamics to protection. Yes means yes... but yes to what? Anyone who's had sex will tell you that "yes" is where the conversation begins- not where it ends.

These interventions are trying to resolve a symptom, without looking deep enough into the cause.They presume that it's rapists who are pushing all these survivors in, and administrators and law enforcement who are neglecting their duties to identify and remove these perpetrators from campus. Or the government failing to enforce equal access legislation. Or careless students failing to look out for one another. All these may play a part in the problem- but to truly prevent this epidemic, we need to look at where young people- perpetrators and survivors alike- are learning about sex.

An "It's On Us" commercial I've been seeing a lot of lately involves a variety of celebrities informing me, "There's one thing you can't have sex without- and that's consent. Without consent, it's not sex. It's rape." We are learning more and more about rape, but where are young people learning about sex? Primarily abstinence only educational programs that encourage students to "just say no," to wait for marriage (even though 95% of Americans don't)- and then engage scare tactics, or share medically inaccurate information. Meanwhile there is no shortage of sexual content in the media, never mind what young people can find on the internet. Beyond the movement to address sexual violence, other millennial feminists are raising awareness of a "bad sex" culture- in which hook ups look more like conquests, and intimacy and mutual pleasure are rare.

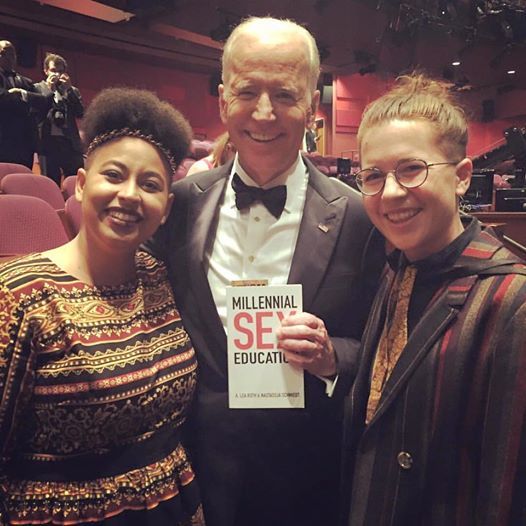

Me (on the right) with my fiancée/co-author, Nastassja Schmiedt, and Vice President Joe Biden holding our book Millennial Sex Education at the Academy Awards

Legislation in Virginia last week mandated education about healthy relationships and consent at the high school level. After talking to young people and activists on campuses around the country, we believe that the best intervention to prevent rape is not just more education about rape- it's comprehensive and inclusive sexual education. Without it, there is no way for young people to communicate and tell the difference between good sex, bad sex, and rape. We need to have conversations about what rape looks like and how to support survivors, but also conversations about how to have sex! That's why my partner and I wrote a curriculum- entitled Millennial Sex Education- that models fictional stories about people engaging with the sexual culture with questions for reflection and dialogue. And that's why we're making an ebook of the curriculum available for free download on our website. Join us in this movement for comprehensive, inclusive sex education- and let's end rape culture together.