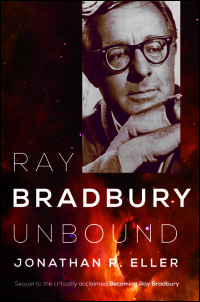

Ray Bradbury Unbound

by Jonathan R. Eller

University of Illinois Press | 2014 | 352 pages | $34.95

Ray Bradbury was a lover. Ray Bradbury was a self-described "emotionalist," a passionate man and writer who worked instinctually and rarely intellectually, and who produced a unique body of work, the best of which was his own brand of metaphorical and poetic prose on subjects ranging from the dark carnivals of our souls to chronicles of a Mars which could never be, exploited by a humanity as it had sadly been. In one of his few novels he called for that humanity not to give up on art and culture by allowing the powers-that-be to raise the temperature to 451 degrees Fahrenheit. And in essays that soared on wings he built himself he urged humanity to never give up the ghost, to instead reach for the stars in order to reach for immortality.

In all of this he was the child of Homer and Shakespeare, Edgar Allen Poe and Thomas Wolfe. He was also the child of Verne and Wells, Edgar Rice Burroughs and Buck Rogers. And these parents were all to the good in the making of this prose artist. But as Jonathan R. Eller points out in Ray Bradbury Unbound, his follow up to his 2011 "biography of the mind," Becoming Ray Bradbury, Bradbury had a third set of parents who were not all to the good, and may well have helped unmake the prose artist: the performance art media of stage, screen, and television.

I reviewed Becoming Ray Bradbury in 2011 for Neworld Review and included the review in my own book, Searching for Ray Bradbury: Writings about the Writer and the Man, calling Eller's a "fine and important book." I have no less of an opinion of Ray Bradbury Unbound, the second of what Eller promises will be a trilogy covering Bradbury's artistic growth, maturity, and late years. At the time I reviewed the first book I did not know Mr. Eller, a professor of English at Indiana University-Purdue University and the director of the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies there. I have come to know him since and I admire him greatly. Indeed, I am listed in the acknowledgements in his book as a fellow writer who gave him much encouragement, albeit with my name misspelled -- Leyva instead of Leiva -- aligning me more with the recently captured Mexican drug lord than the literary world. Despite this, I have determined to be fair to Mr. Eller.

A big part of Ray Bradbury's story are the many mentors who helped him to shape his raw artistic talent. Eller did a wonderful job of research, scholarship, and textual investigations in Becoming Ray Bradbury to discover Bradbury's early mentors. These included Henry Kuttner, C.L. Moore, Edmond Hamilton, and Leigh Brackett -- science fiction writers all -- who saw that Bradbury's talent could and should expand beyond their genre. They encouraged him to read widely in literature and to submit his stories outside of the pulp magazines he first broke into. And to never, never "write for the market," but to always stay true to his own highly individual style. It was not hard for Bradbury to heed their advice -- he wanted wide literary success and he despised writing to a formula -- and he soon built a particular literary career, unlike any other, that made itself known to the likes of writers Christopher Isherwood and Aldous Huxley, philosopher Bertrand Russell, and even the grand art historian Bernard Berenson, all of whom expressed admiration and gave encouragement. A most desired situation for any writer of prose -- to be mentored and encouraged by other writers of prose. But Becoming Ray Bradbury ends with Bradbury meeting and impressing an artist in an aligned but fundamentally different art: film director John Huston. In 1953 Huston tapped Bradbury to write the screenplay for his next film, Moby Dick, bringing him along for a long stay in Ireland and a descent into a certain kind of hell.

Huston was the seductive devil. But Bradbury was not an unwilling disciple.

Bradbury had loved movies from early childhood, seeing and being existentially affected by Lon Chaney's performance in The Hunchback of Notre Dame at the age of three. Eighty-six years later he declared with joyful hyperbole in a video of him I produced for the Buffalo International Film Festival, "I've seen every film ever made, I'm a child of motion pictures, I'm the world's greatest lover of movies." One of his favorite filmmakers of the 1940s was John Huston and in 1951 he convinced his media agent Ray Starke (Bradbury had been selling to and occasionally scripting for radio since 1946, and was just breaking into TV) to arrange a dinner with the director of The Maltese Falcon. "The evening went well," Eller writes, "perhaps because Starke could vouch for the growing Hollywood interest in Bradbury's work." Bradbury brought along his three published books to date -- Dark Carnival, The Martian Chronicles, and The Illustrated Man -- and gave them to Huston, declaring, "Mr. Huston, it's very simple. I love your films, I love you, and if you love these books half as much as my affection for you, I want you to hire me someday."

Eller narrates this scene at the beginning of Ray Bradbury Unbound, then details what came of this dinner. Huston read and was impressed by the books -- "most beautiful & wise & moving," Eller quotes from a letter Huston wrote Bradbury within two weeks after the dinner. After making The African Queen and Moulin Rouge, and after briefly thinking of making a film of The Martian Chronicles, Huston read Bradbury's short story "The Fog Horn" and knew he had found the screenwriter for his production of Herman Melville's Moby Dick. It was a daunting task, Bradbury had not even read the novel. But he dived into it here and there, was impressed by the Shakespearian and Biblical power of the prose in parts of the book, and agreed to do the job.

Suddenly Bradbury goes from being a most unique and individual writer of short stories, earning just enough for his family of wife and two daughters to get by, to being a more than well-paid screenwriter earning enough in salary and travel and living expenses to take his family -- and a governess -- with him for the contracted seventeen weeks of work in Ireland. There, under Huston's direction, Bradbury would figure out how to bring Melville to the screen. For Bradbury, the lover of films, it was a dream. Sadly, the dream turned into a nightmare.

Huston, a great film artist, was a mean bully of a man. Or just a man's man, a hard drinking, big game hunting, small game chasing, woman pursuing and emotionally abusing, yet charming to some, bigger-than-life font of masculine musk. In either case, not someone who, despite genuinely admiring Bradbury's talent, seemed able to let this gentle lover of words and dinosaurs and the stars, this man who married the first girl he ever dated, this man who did not drive, would not fly, and would not think to hunt an animal to death, it seemed this kind of a man Huston could just not let be himself. It was as if Bradbury himself was an affront to Huston himself. The challenge had to be met. Huston, "could not resist toying with people who idolized him or who showed weakness. Bradbury was vulnerable on both counts, and Huston very casually hit his weak points from time to time.... preying on his (Bradbury's) fear of being trapped in a speeding car and his abiding fear of air travel." Huston's needling and the pranks he pulled on Bradbury, such as faking a telegram from the film's producer demanding that a "RICH WOMAN'S ROLE," be written into the script -- a story of men at sea hunting a great white whale -- reduced Bradbury to tears, and "began to sap his confidence as a writer."

And yet, Huston was both muse and mentor to Bradbury, who learned much about crafting a film script and, in the end, delivered a masterful screen adaptation of a complex work of prose. But the experience also made Bradbury gun shy about taking on any other film assignments for several years after the release of Moby Dick, despite the film's success having made him a hot commodity in Hollywood. He was considered for and/or turned down such films as The Friendly Persuasion, Diabolique, The Man with the Golden Arm, War and Peace, and Good Morning, Miss Dove. Eller reports all this dispassionately, which is proper for a biographer, but still hints that it might have been better for Ray Bradbury, the master of prose, if he had remained gun shy.

But the siren call of the silver screen eventually got through to Bradbury again and he spent much of his creativeness in the 1950s and 60s proposing, writing, and trying to sell screenplays to Hollywood. Some were assignments, most were adaptations of his own work, all diverted him from the writing of prose fiction, the kind of writing he was so prolific at in the 1940s and which had made his reputation. In the 1950s and 60s he worked with such film talents as Sir Carol Reed, Burt Lancaster, Gene Kelly, and Francois Truffaut. Although some of his Hollywood experiences were good (his work with Reed was as wonderful an experience as his work with Huston was as awful a one), given the time and effort Bradbury put into his relationship with Hollywood it was rarely a happy one. A not unusual situation for a writer from the literary world emigrating to the filmic world; F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner being the classic examples.

Fitzgerald, a forgotten novelist, died a broken screenwriter. Faulkner was more successful in Hollywood, but was always homesick for Oxford, Mississippi. Both, I'm guessing, had little true love for screenwriting, the products which came from screenwriting, and the Hollywood industry, which had little true love for writers. But Ray Bradbury did. It was an art, a world, he very much wanted to be a part of. The difference may well have been the fact that Bradbury, born in 1920, grew up in a world where film entertainment quickly established itself as a native part of the landscape. Fitzgerald, born in 1896, and Faulkner, born in 1897, grew up in a world where film entertainment was an invading alien. Bradbury's young mind had been imprinted with film.

To his detriment? As a man, no. Bradbury derived great joy from film and, I believe, from his association with certain film artists. Bradbury was a man who embraced joy. As a writer? Possibly by way of an answer Eller points out that Bradbury's outstanding fiction was published during only two decades, from 1942 to 1962. That in 1967 this writer who had been so prolific in prose published only one short story. 1968 became the first year in 28 years that Bradbury published not even one new story.

Film was not the only culprit. There was television and there was live theater (Bradbury maintained his own theater company for decades producing adaptations of his work). Bradbury, who became a natural public speaker, spent much time and energy in lecturing with abandon and enthusiasm and inspiration on writing, urban planning, and the future of humanity, and was rightly applauded for it. Then there was his advocacy for the space program and the non-fiction pieces he wrote supporting it for Life magazine. But film, being the elephant -- or maybe in Bradbury's case, the dinosaur -- in the Twentieth Century room, I've chosen to concentrated on it in this review. Eller, however, properly gives equal space to all the various activities that Bradbury involved himself in that, while fulfilling needs and desires he had, may have robbed the rest of us of a continuation of his true talent. For words were Bradbury's brush and paint, his chisel and marble, his notes and instrument, the wet clay beneath his fingers. Words manipulated onto a page -- emotionally, instinctually, passionately -- into sentences, into paragraphs and prose poems, and into stories taking us deep into our dreams and nightmares, way back in time and far out in space, both cautioning us and celebrating us, was the very best he could give of himself; the very best he could give to us. It is the intimate, one-on-one relationship of readers with Bradbury and his prose that will endure and always be the basis of his future reputation.

In Ray Bradbury Unbound (a lovely title with at least two pertinent meanings) Eller perfectly chronicles what happened to Bradbury the prose artist in the 1950s and 60s. He details the spin of activities that took Bradbury away from that which was the core of his art and talent and into other areas that were at times satisfying, but more often frustrating. He does not condemn Bradbury for the choices he made, but the reader cannot help feeling the underlying sadness that seems to be there, a melancholy regret for the sharp metaphors unborn, the unique visions not presented, the engaging stories unwritten.

----

Leiva is a novelist. His latest work, By the Sea, a comic novel, will be published early next year by Crossroad Press. In 2010 he created and organized Ray Bradbury Week in Los Angeles in honor of Bradbury's 90th birthday.