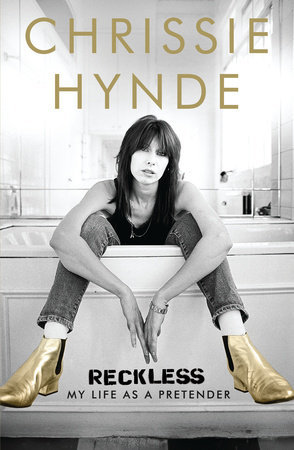

In the 1979 Pretenders hit "Brass in Pocket," Chrissie Hynde insisted there was nobody else like her--and she was correct. Yet the girl we meet in the early pages of her heartfelt and beautifully written memoir, Reckless, is like millions of other cool kids in the sixties who were obsessed with music, became very adept at lying to their parents, and did a lot of drugs.

Hynde's description of her childhood in Akron in the 1960s--middle-class home, leafy streets, and strict, conservative, loving parents--is of a quintessential, sweet, boomer childhood. The details resonate: Ginny and Midge dolls, a brother's Mad magazine, a young girl's obsession with horses, tree forts, Davy Crockett hats, sharpening popsicle sticks on the sidewalk, and bedroom décor with a cowboy motif. If anyone had asked her at the time, she'd have said she wanted to be a cowgirl when she grew up. "Nothing that happened to me was particularly unique," Hynde said recently in an interview on Canadian radio. But somehow she became Chrissie Hynde (a cowgirl of sorts, one could argue). With reflection, insight, and humor, Reckless reveals how that happened.

As I discuss in my book Beatleness, boomer childhood and adolescence changed overnight in February '64. Music became a focal point, a necessity. The Beatles ushered in not only the British Invasion (which made us all Anglophiles) but a pop music renaissance. We were captivated by the music and by the effeminate young men who wrote and performed it.

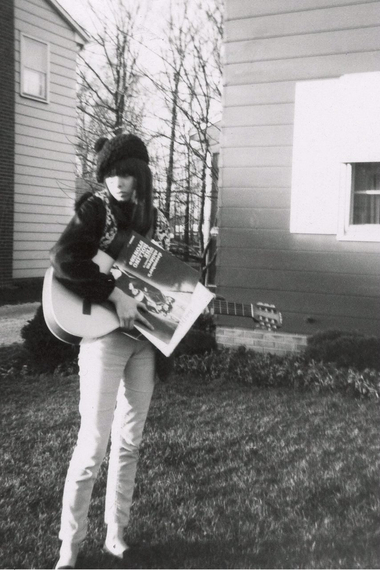

Like millions of boomer girls, Christy (not yet Chrissie) saw a photo of Jane Asher in 16 magazine and changed her look. The ukulele she'd been given as an Easter gift was tossed aside for a guitar. Like millions of boomer boys, she wanted to play the guitar and imagined being in a band. She learned a few chords and wrote love songs to Paul McCartney. As Hynde went through her adolescence, she internalized the gender sensibilities of her female and male peers in a way that made her increasingly peerless.

It's often said of the era that girls wanted to be with the guys in the band and that guys wanted to be in the band. But in those days, it wouldn't even have occurred to most girls that they could be in a band. There were few role models. Girls didn't wield electric guitars. Acoustic, maybe, but as one Beatleness interviewee told me, "I didn't want to be Joni Mitchell, I wanted to be John Lennon."

Nothing brought the teenage Hynde more joy than getting high with her friends and going to hear her favorite bands. Again, not unusual. But somehow, through a combination of serendipity and chutzpah, Hynde was able to meet many of her idols before she was even out of high school, including Jackie Wilson, Cream, the Kinks, Paul Butterfield, Rod Stewart, Jeff Beck, and Iggy Pop. After the thrill of seeing Bowie with the Spiders in Cleveland she somehow found herself cruising around the city with Ziggy himself, in her mom's Cutlass. She first locked gaze with Ray Davies, her future partner and father of her first child, after a Kinks show in 1970.

From the book's opening pages, it's clear that young Christy was easily bored and craved stimulation. She was an adventurer, needing freedom and autonomy to feed her hungry sensorium. Believing that "comfort doesn't bring creativity," she happily gave up the comfort and safety of her parent's home.

Hynde's vivid language and clear voice give the book a cinematic quality, with several laugh out loud passages. Like a vagabond with a purpose, she collected experiences some of which could easily have led to her demise. Hanging with druggies, bikers, and other outlaws, she developed street smarts which combined with her raw intelligence and intuitive sense of how the world works, giving her a fine set of survival skills. Coincidence, charisma, and a warm heart allowed her to find just enough like-minded companions along the way. She was adept at identifying moments that could advance her mission, even if she wasn't exactly sure what her mission was. She thought if she kept not doing what she didn't want to do she'd eventually stumble on what she did want to do.

Hynde enrolls at Kent State University, but rarely attends class. She enjoys living on her own, relishing the simple freedom to sit on a stoop eating a slice of pizza, and hanging out with her fellow misfits. She manages to talk her parents into a semester in Mexico, where she parties with all manner of interesting and dangerous people. Reckless, yes, but also fearless. By choice or chance, the more tough situations she experiences, the more fearless she seems to become, and the more she hones her survival skills. She was on the scene when the National Guard opened fire on student protestors, killing four, including her friend's boyfriend.

Through a series of decisions--good, bad, and some made by default--Hynde gradually changes her trajectory and leaves even the coolest kids behind. She comes to realize that the thing she wants most is to be in a band. Thus begins a meandering, indeed reckless, though vaguely focused journey.

Her disdain for car culture and the need to flee bikers takes her to London in '73, where she experiences public transportation and real urban life for the first time. Falling in love with the city, she soon finds work (including a stint as a writer at the influential NME) and like-minded people to hang out with (including Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood), while wrestling with imposter syndrome and splashing around in the rich primordial soup of the punk scene. She briefly played in an early iteration of the Clash, and hung out with Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious, almost marrying one of them so she could stay in the UK. Her musical skills, attitude, and style were a perfect fit for the emerging aesthetic, and she got serious about forming a band.

The happiest moment in the book is when Hynde realizes that she, Peter Farndon, James Honeyman-Scott, and Martin Chambers were a band. Hynde loved working with them. She felt lucky and proud to have discovered them and proud, for them, of the many accolades they received from musicians they respected. Though Hynde was adamant about not being a solo act, it was her elegant edginess, front and center, that distinguished the Pretenders. Hynde's female embodiment of male rock androgyny was compelling. Her tough and tender lyrics reflected her experiences, as did the emotional palette of her extraordinary voice.

Success and fame were stressful. In 1982 she fired ex-lover and bass player Farndon because of his drug abuse. Honeyman-Scott died of drug-related causes two days later, and Farndon was dead within the year. Hynde was devastated. For herself and for them, she kept the band going, with personnel changes over the years, grateful for what they helped her become.

The self-effacing Hynde might dismiss the notion that she could be an inspiration to millions, but she is, and not only to musicians (I thanked her in my doctoral dissertation in the '90s). Reckless is more than a well-written, thoughtful memoir. It's a cultural history of the rock scene in the 60s and early 70s, told by an astute observer who, perhaps unwittingly, reminds readers that improbable dreams can come true. If confidence is "a bluff" as Hynde says, then she truly is a great pretender.