'Let him speak who has seen with his eyes' - Congolese proverb

This proverb is going to become the philosophical touchstone of my Congo expedition; at least I hope it does. When I found it, while doing preliminary research for the trip, it made an immediate and powerful impression on me. I had struggled to commit to the expedition for many reasons, not least of which was trying to understand the rationale behind my desire to walk the length of the river.

Reflecting on my motivations for taking on this challenge, I became acutely aware of how sensitive I would need to be in the way that I presented both myself and the expedition. Can one really use a journey through a country that has been as harried and exploited as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) as a means for self-discovery? I believe It would be both irresponsible and disrespectful to set out on this expedition without recognizing the often dismal impact that exploration has had in the Central African region, and in particular the consequences that it has had on the country now known as the DRC.

The first contact that Portuguese sailors had with the inhabitants of what was then the Kingdom of Kongo were initially peaceful, if paternalistic. However, within decades, commercial ambition led to the internationalization and immense scaling of a slave trade that had been local and of relatively small impact. The Kongolese Kingdom as a systematized source of slaves from neighboring territories accounted for a hugely significant number of slaves transported to the Americas as part of the transatlantic slave trade.

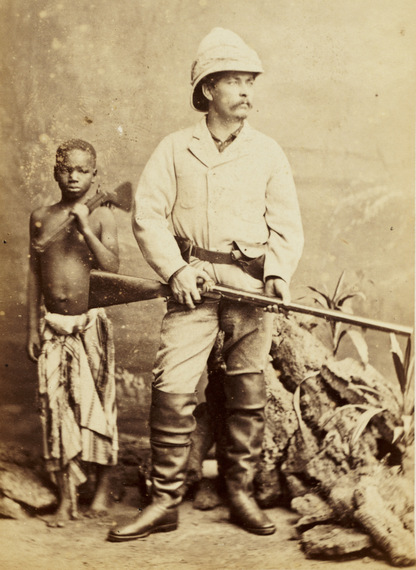

Henry Morton Stanley -- a Welsh explorer and journalist who travelled in the latter half of the eighteenth century -- is a man whose expeditions are generally regarded as having been cruel, racist and exploitative. As an explorer, one is conflicted in looking at Stanley's record; despite the use of unconscionable methods, one cannot ignore the incredible determination and perseverance that he required to succeed. His first trans-Africa expedition - 999 grueling days from Zanzibar to Boma - is an epic of survival that has been rarely matched.

Stanley's more damning legacy, however, is the role that he subsequently played as a representative of King Leopold of Belgium in that man's annexation of a vast swath of Central Africa that came to be named the Free Congo State. Leopold then imposed a brutal system of forced labor in the Congo. The fears provoked in other European powers by Leopold's vast land grab were a key driver of the Scramble for Africa, Europe's colonization of the continent.

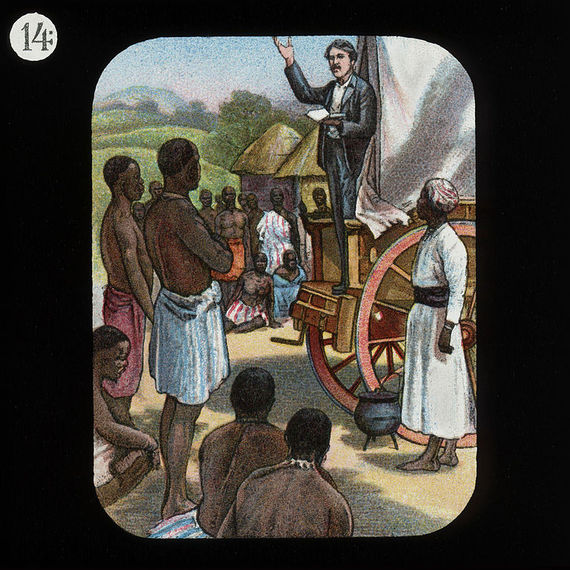

That is not to say that those who have sought out the hidden corners of Central Africa have been uniformly ill-intentioned. Dr David Livingstone -- of whom you have presumably heard -- was for the most part well-regarded, admired by the tribes with which he came in contact and a man who played a significant role in inspiring anti-slavery sentiment in Europe. Even here, however, the situation is complex, with the doctor forced to rely for survival upon the very Arab slave traders he was later to condemn.

In the last few decades, expeditions have for the most part been undertaken with an emphasis on self-sufficiency and cultural sensitivity. Then-Major John Blashford-Snell, leader of a huge 1974 British Army scientific expedition down what was then the Zaire River said, "We had come not to conquer Zaire, or its people, but to fight the invisible enemy of disease and to discover the scientific secrets of this vast land."

Phil Harwood is another fellow Briton; apparently we are drawn to this part of the world. In 2008 he canoed, alone, the length of the Congo River. By his own account he was brought close to breaking point by his struggles. And yet, despite the constant physical and mental pressure he endured, he was able to maintain a sense of perspective, "I experienced swamps, waterfalls, rapids and endemic corruption," he said. "Arrested, chased, collapsing from malaria with numerous death threats, I also encountered tremendous hospitality and kindness from a proud and brave people long forgotten by the western world."

I feel that Phil's journey, and his account of it, is one that I will draw on heavily for inspiration as I progress: an incredibly bold expedition recounted with a striking honesty. Dangers and setbacks are not ignored, but nor are they overly dwelled upon. Encounters with troublemakers are noted, but the need for an aggressive response is, almost always, regretted. It is telling that, on his arrival at the Atlantic, he leaves his trusty canoe with a fishing community near the mouth of the river, a tribute to the fishermen on the river who provided such a consistent source of support.

I know that, at heart, I want to discover something about myself through this journey; it is undeniably self-centered. I am not going to go looking for trouble, although I dare say I will not avoid it entirely. Whatever happens, good and bad, I commit to telling this story -- my simple story of walking down a river in Africa, honestly. I will indeed speak of what my eyes have seen and hope that in those recollections there may be some value to be found.