Michael Arad is someone you need to listen closely too. At first, he seems soft-spoken, almost as if he found himself with a bigger job than someone of his age and experience should reasonably expect.

But as New York, and the world, prepares to see for the first time what will most certainly be one of the most visited memorial sites in the world -- Arad seems calm, focused, and comfortable with what they'll see.

What you see, where it comes from:

On September 11th, 2001 -- the towers fell as the world watched. 2,977 victims lost their life. And for anyone who was living in New York -- the sounds, the images, and the smell will never be forgotten.

Ten years to the day -- the site will re-open, this time as a memorial. What has been created there is remarkable in its simplicity and its powerful poignancy. Thousands of craftsmen, engineers, historians, and curators have worked to build a memorial that will welcome visitors from around the world. But make no mistake about it -- the Memorial is the vision of American-Israeli architect Michael Arad, who began sketching images of empty tower 'voids' just days after the attacks.

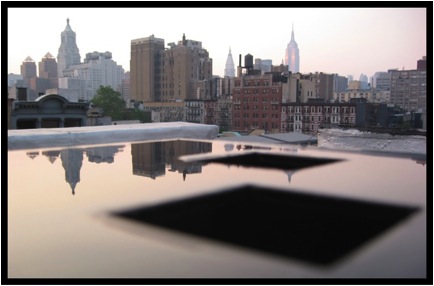

The memorial's perhaps most dramatic feature is what is not there -- the empty sky above, and the empty tower footprint below where the towers stood. The design has evolved since the days just after 9/11 when architect Arad looked out on the Hudson River and imagined two holes carved into the flowing river.

His story -- like those of so many New Yorkers -- is etched in his mind.

"My wife had to be at work early that day. She worked in the Financial District. And I heard on the radio that the World Trade Center had been hit by a plane. I thought it must have been a small plane, some sort of freak accident. I was in the bathroom shaving, I walked across our apartment in the East Village to look out of our bedroom window where you can see the towers. And you could see this whole plum smoke rising up from the North Tower."

Having grown up in Israel, Arad was no stranger to terrorism. Bombs would go off on bus routes that he and his friends used to go to school. Yet here, in America -- he thought he had left that world behind.

"I feel like I lost something and gained something in that moment. All of a sudden I was a New Yorker. It's kind of an odd. One thing rushed in and another thing rushed out. I lost that sense of peacefulness, that life can be normal. Yet at the same time, the sense of connectedness, of being part of a greater whole came in at the same time."

Later that week, Arad ended up at Washington Square Park around 3:00 a.m. "I stood there as part of a circle of people, all of a sudden I felt connected. I didn't feel alone and the sort of sense of doom and despair that was hanging over everything seemed to have lift a little bit."

"I think the memorial that I've designed draws on those feelings of creating a place for people to be together. Place for somebody, place for gathering so that as you come here and you confront the history of that day even if you come here alone, you're not alone."

The Void. First, in the Hudson River

Unable to find work in the days after 9/11, as his H1b Visa renewal was tied up in new INS and Homeland Security review polities -- Arad found himself thinking about the Towers, and how their loss could be memorialized.

"The idea for a memorial I had was two voids which would be cut into the surface of the Hudson River. If the river is frozen, you could cut a void into it. But the idea was really that the water -- cut into the surface of the river as the water flows, and that can't be done. And sort of this sort of an inexpiable image like how do you like put a hole through the surface of time or something like that? This idea kind of obsessed me and I kept sketching it."

Together with help from Canal Plastics and volunteers at Awad Architectural Models, Arad built the first prototype, using parts from a fountain he purchased at Bed Bath and Beyond.

"And I thought about this and sketched this for so long and at the completion of these two days work all of a sudden like we plugged it in, we poured the water, and you could hear it gurgling to life so to speak, and all of a sudden you could see that flat surface materialize and the voids appear."

"For me it was a really magical moment."

The Contest: Why rules are made to be broken

When Arad heard that there would be an open call for architectural designs for the Memorial, he knew he had no chance of winning. The city had chosen Daniel Libeskind to do the site master plan, and the setting and design limits were clearly defined. Contest entrants would have to fit their Memorial inside the approved Libeskind site plan.

"I felt like the master plan essentially was very much a Memorial design already. So I said these are the guidelines but I'm just going to imagine whatever I'd like to visit and send that in knowing full-well that I was violating the competition guidelines."

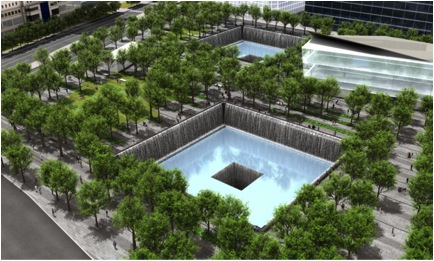

Arad's design, which won the competition and is now essentially what is being completed at the site is called "Reflecting Absence". A vast flat plane of a Memorial Plaza being punctuated by these two larger voids which were cut into the surface of that plane. It was clearly the original idea that Arad had conceived with the initial model that created two voids in the heart of the river. But the balancing act was far from over.

"How do you balance these two seemingly contradictory goals of creating a sort of hallowed place for memory but also a vibrant and alive part of the city that welcomes people back. I mean, you can imagine office workers coming down here and eating a sandwich during their lunch break and at the same time also having that visitor that comes once in their life and wants to have a very meaningful moment of reflection about the past. "

Changes: The Evolution of the design

Since Arad won the competition, the design has changed in two significant ways. The landscaping, what was by some descriptions barren, has evolved from 50 trees to more than 400 as Peter Walker Architects was brought in to partner with Arad as the design evolved to fit the site and the many stakeholders.

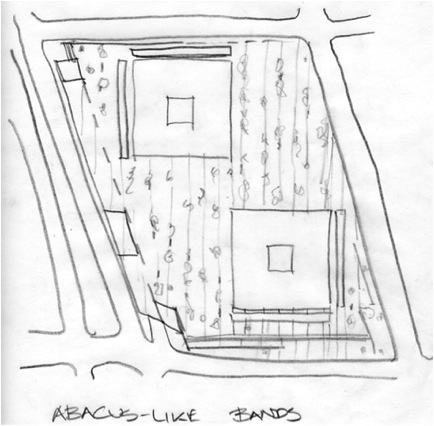

"I didn't want something that had a very clear geometry to it, something like a grid of trees that would compete with that very strong gesture of the pools. So I came up with this idea that I call the Abacus-like bands of trees. And as you look in one direction you see this sort of clear allays of trees forming. And then as you turn 90 degrees it has this look that is almost random natural forest not truly because you're on this like vast flat landscape but the trees are arrayed very loosely."

"And the idea was also to clear this space between the Plaza under your feet and this canopy over your head, so you ended up doing is creating this large urban room in the middle of the city where you have the sky overhead which is something you rarely see in lower Manhattan."

But the change that was more fundamental, and core to Arad's original design was the decision to bring what was the Memorial Galleries up from below-ground to the plaza level. The original design called for the names parapets to wrap around in a band at the bottom of the voids. A plan that the family members and city safety officials both fiercely opposed.

"It was a very painful journey. And that was the moment where people that were urging me to walk away from the project at that point."

But Arad did not walk away -- instead staying engaged and working to keep the core spirit and concepts of the design in place.

"I feel that in this process we lost some things but nothing that was added to the Memorial that would destroy that initial design direction that was there. I think it's gone through an editing process."

In the end -- the cool, dark private viewing of the names that would have brought visitors down long ramps to bedrock where water from the falls would have created a curtain that rolled over the names is gone. The names have been brought up to the surface, to the sunlight. A change that Arad now accepts.

"I was very attached to the idea of the memorial galleries and sitting here a few years after we made the design change that eliminated them I'm at peace with the Memorial as it is today."

"I think in light of the day like the Memorial is what it is thanks to the fact that I did stay involved in it. And I think that it is a very strong and clear design. The challenge of dealing with how do you interact with the names now that it's no longer within the sheltered space of the memorial gallery but is actually up on plaza level was something that we struggled with extensively and I think we have a design that addresses that. It was not an easy process, not quick but we got there."

The Names: The Order in Randomness

Conventional memorial design would have had the names of the victims in alphabetical order, with special insignias to denote first responders. But almost from the start -- Arad wanted the names arranged differently.

"We wanted to find a way to engage the family members in this process of placing the name of their loved one on the Memorial. So we asked them are there names of other people who died that day that you'd like to see next to the name of your loved one and call this Meaningful Adjacencies."

Today, what appears at first glance as a random array of names is anything but that -- It reflects the lives that people had. The names might be people that they went to school with or commuted with or worked with or friends and relatives.

"I think it's so hard to relate to the death of close to 3, 000 people all at once but when you hear of a specific story about somebody losing a brother or somebody losing a daughter, a parent, we can relate to that. "

The Waterfalls:

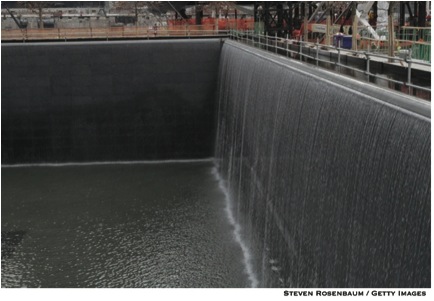

Each pool has 16 pumps capable of pumping water at 3,000 gallons a minute. Each will hold about 480,000 gallons. Water is taken from city mains but is re-circulated once it arrives at the memorial.

"I remember the first time they turned the waterfalls on and you could just hear this beautiful sound track that is it's not very loud, it's soft enough that it's present but not overwhelming of conversation by any means. And it really -- it animates the site in a way. It brings life to it and a lot of it acts in some way almost like the passage of an arm and a clock, you could see time passing by. And it's like the constant motion is a marker of the passage of time. And I think I wanted that sense of water filling this -- flowing into this void but never filling it up. That sense of continuing absence of the -- that can't be erased. That isn't mitigated by the passage of time."

What It Means. Why It Matters.

The process of the city, the nation, and the world coming to terms with the attacks on the Twin Towers is hardly over. Historians caution that the real 'history ' of 9/11 won't be written for more than another ten years. Yet for Arad, the need for the site to be both a remembrance and a vibrant part of the city created a challenge that he was anxious to serve.

"The site is really an integral part of the city. If this is a scar, it's not a scar that we're hiding. It isn't one that we're celebrating. It's one that it's just there, its just part of the city. You neither need to sort of scream and proclaim it and neither do you want to hide it. It just needs to be a part of the everyday life of New York."

As construction continues around the WTC site, access to the Memorial will be free, and timed tickets will be offered to assure a smooth flow of visitors from 9/12 onward. You can reserve tickets now at the National 9/11 Memorial Website HERE.

Visitors to the site will find a vast expanse of sky, a large flowing plaza with a veritable forest of swamp oak trees, and in the two towers, two massive open 'voids' -- their perimeters incised with the names of those who lost their lives, and the largest man-made waterfall in the world pouring more than 3,000 gallons of water a minute over the edge of the parapet and down 30ft to the void below.

You should see it for yourself.

Steven Rosenbaum is a filmmaker, entrepreneur, and storyteller. He is the author of the forthcoming book and film Making The Memorial and Museum and a regular visitor to the site since 2001, when he made his first film on the subject, 7 Days In September.