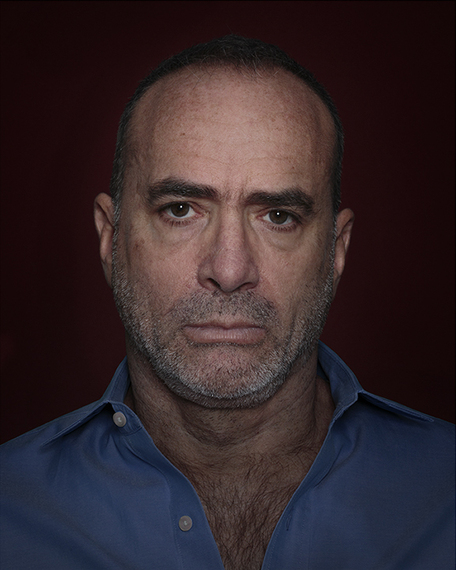

@2014 Frank Yamrus

from his ongoing series a "A Sense of a Beginning"

Portraits of Long Term Survivors of HIV

When Frank Yamrus was taking my photo, the bag I'd brought to the shoot with different outfits was left in the corner. "The solid blue shirt will work fine," he told me. Contrary to my Vanity Fair photo-spread delusions of grandeur, there weren't going to be a series of different poses all over the studio, as Frank played with wardrobe and lighting. Instead, I sat in the same chair as everyone else, close to the camera, prompted gently to let my facial expressions relax as much as possible.

When Frank agreed to let me write this essay, I asked to take an advance look at some of the other photos. I saw them iPad-sized, one scrolling onto another in perfectly coordinated dimensions. My initial thought was of Portrait Day in elementary school, as each face filled exactly the same space in the frame, against the very same background.

At first, the stylistic consistency between the photos seemed an odd choice to me. For years, many of us had been thought of as "my friend with AIDS," or "my HIV-positive uncle." As the crisis subsided, it felt, finally, as if it was no longer the first adjective that came to mind when those we love thought of us. Shouldn't these portraits, I thought, be an opportunity to celebrate our individuality in spite of our HIV, rather than our sameness because of it?

Clearly, if that's what Frank wanted to do, he could have -- his other work is thoroughly eclectic, even unpredictable. So I sought to understand what he was aiming to create. Bearing in mind that the aesthetic he chose for this series could only be intentional, it became clear to me that by making each portrait as consistent as possible, Frank was stripping away all distractions for the viewer. No matter which photo, it is virtually impossible not to focus on the one element that is never the same, even when everything else is: the eyes.

I don't know if the eyes are truly the window to the soul, or if the particular essence of living with HIV for so long can be captured by any camera. It's almost as if we'd need to know what we would have looked like in an alternate universe where AIDS had never existed, in which our lives hadn't been irrevocably translated by it, divided forever into before and after the moment we found out that sex could actually kill us. I'll never know what you would have seen in the eyes of the "other" me. But I can share some of what I have lived through, some of what you might be seeing in my eyes and in the eyes of many in these portraits.

Seroconverting in the 1980s meant that time assumed a dyslexic quality for me; entire decades were flipped around. In my 20s, I started checking the obituaries before the headlines; in my 30s, I went on disability. For the next two decades or so, I often lived beyond my means, confusing instant gratification with being in the moment. Eventually, surviving meant returning to the workforce in middle age. Now I will almost certainly have to work as long as I physically can. Seems fair enough. Retirement? Been there, done that.

Obviously, many friends got sick and never got better. I learned that there is an art to visiting someone in the hospital, but that no one ever masters the best way to help someone die. I got scarily adept at writing eulogies, wondering as I delivered them if those gathered recognized the same suit I'd worn the last time, and the time before.

Once I was swapping stories with a bunch of "last men standing." We kept topping each other with numbers of friends and lovers lost. After a pause, I shared a sudden epiphany: "Oh, my God, we're grief-competing!" We laughed so hard. We had to laugh. There was nothing else left to do. (Loss on that scale is unarguably dreadful, but truth be told, it can also make you feel a little bit important.)

Then, in the late '90s, I staggered from the desert onto an oasis, fairly sure it was going to end up being a mirage. I dutifully swallowed all the new pills -- so many pills! And the side effects -- let's not forget those, even the times I blamed them to get out of doing something instead of owning up to nursing a hangover. I slowly noticed I was hearing terms like "viral load" and "genotype" far more frequently than "PCP" and "Kaposi's Sarcoma." When my doctor first pronounced me "undetectable," I joked that it sounded like the title of a summer blockbuster.

"No," he smiled. "It means we can barely find HIV in your blood."

Say what?

"You're going to live, my friend. AIDS is not going to kill you."

Oh, I see.

(Pause for effect.)

But what's the good news?

Clearly, I'd neglected to inform the doctor I could not afford to live. Did he know how much I owed on my credit cards? And then there was that Master's degree I'd completely forgotten to get. Not to mention perhaps maybe a teensy-tiny crystal meth habit I'd picked up, the one I was able to completely justify because I had a two-year life expectancy and the paperwork to prove it.

Here's the thing about the future. It's not real, it's an idea we have in our head. Survivors like me didn't even know how much space it took up in our consciousness until it started shrinking, no longer the rapidly expanding universe of anticipation it was before HIV. I know when I confronted the very real prospect of dying young, I deliberately hastened my shift in perspective. It was far less painful to expect the worst and be prepared for it than live in denial and get mugged by reality. I'd seen some friends do that, and they did not go peacefully.

What did Bette Davis say? "Growing old ain't for sissies." Well, it ain't for narcississies either. I dreaded the ego-puncturing years of turning fewer and fewer heads, of remembering when they used to call me "Sir" for a completely different reason. Sure, early death was scary, but calling a truce with it was so much less exhausting than fighting a battle I was sure to lose.

That was a smart strategy for the time, but dammit, it only worked if you actually died. Gradually, I realized I'd have to glue back all those pages I'd ripped from my calendar, crawl back to the ex to whom I'd so dramatically bid adieu years before. Hey, future, remember me? We used to be tight. Made lots of plans back in the day. Well... I was thinking we could let bygones be bygones and give it another whirl. Whad'ya say?

It took me a few years to put a name to this entire syndrome, but I even used it for the title of my Master's thesis (oh, yeah, I finally remembered to get one of those.) I called it: The Disorientation of Survival. It doesn't mean I wasn't grateful for this unexpected turn of events, just that it caught me -- most of us, I think -- off-guard. Sort of like starring in a play and finding out in the second act that they've added a third act, and you're going to have to learn all the new lines during intermission.

"I'm still here," is the caption that would fit under each of Frank's photographs. But in our eyes, you might see a question mark at the end of those words, representing the touch of surprise that we made it. I'm still here? Really?

Really.

"The Longterm Survivor Project" is on view at the SF Camerawork Gallery in San Francisco until July 18th.