This is Part Three of the seven-part series, XX CHROMOSOCIAL: WOMEN ARTISTS CROSS THE HOMOSOCIAL DIVIDE. Part One, with its list of installments and the artists featured in each, can be found on HUFFINGTON POST here.

Art long outlives the institutions and ideologies it is made to service. But if the homosocial ordering of sexuality and gender prove the exception -- if men and women cling to the gender coding handed down to them over millennia along with its art -- it's because the bonds of homosocial desire take root in familial desire: the bonds of fathers with sons and mothers with daughters, both replicating out into homosocial dynasties that over time compose societies and civilizations--all cleaved in two but for the humanity they share.

Even feminism and gay pride, with their objectives to empower and equalize, didn't start out with the objective to scramble the homosocial supports they largely relied on for their own strength. In fact, in the 1990s, some of the most astute women's art reflexively sought to mirror the generational relay of homosocial codes itself. But by turning their focus -- often literally the focus of their camera lenses -- in on the relay and reinforcement of women's homosocialization over succeeding generations, women artists not only sought to secure the longevity (and by implication the perpetuity) of feminist codes for women's sexuality, reproduction and gender, they also stepped analytically outside the chain of feminist art and critique to broach the larger homosocial discourse analyzing the dissemination of sex and gender codes on both sides of the homosocial divide.

Artists using photography to make, document or inform their art were particularly well-suited to singling out not just the codes of the feminist homosocial, but in depicting the actual relay of those codes from generation to generation. We see this particularly in the photographs of Carrie Mae Weems, Sharon Lochkhart, and Catherine Opie, the photo documentation of Vanessa Beecroft's performances, and the paintings of Lisa Yuskavage that are derived from media imagery. By zeroing in on the codes that underpin and perpetuate women's homosocialization, these and numerous other women artists not only tapped the unsurpassed function of art to act as a mirror of its makers, they also found the exceedingly rarer facility of art enabling them to project the collective desire of an avant-garde that has stumbled upon a new code of social behavior to impress on the larger culture.

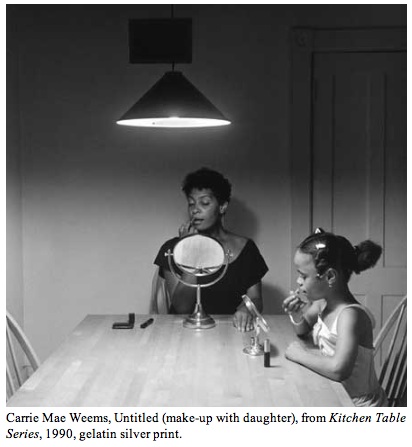

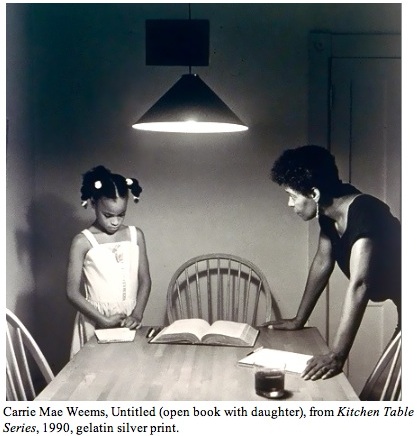

Counting among the most significant reflections in feminist art of the 1990s is that manifesting the historic (and prehistoric) relay of gender codes from mother to daughter as a means of reinforcing the longevity of feminism. On this count, Carrie Mae Weems's Kitchen Table Series (1990) is singularly important. In her photographs of a young daughter mimicking her mother in the act of applying make-up or in learning and writing down lessons from a book, Weems places the enculturation of women's codes front and center of the photographic tableaux to depict the very processes that most women undergo as girls and which they, in their turn, will imbue to the next generation of women-in-formation.

In the lipstick-lesson scene in particular, Weems has seen to it that the iconic image of the girlchild in formation not only directs attention to the homosocial bond between mother and daughter, the artist also explicitly asserts the desire of girls firstly to compose themselves homosocially. Meaning that girls' first attention is largely not to boys and men, but to women and other girls, specifically the mothers, sisters, and girlfriends they learn from and compare themselves to long before they (if ever) appeal to male desire. It is a scene too brimming with filial trust and desire to be dismissed as cliché, which is why it is played out in myriad households around the world. But Weems here turns the light of epiphany on this simple everyday scene so that we can see the time and place women begin disseminating the feminine -- and now the feminist -- homosocial coding for a new generation.

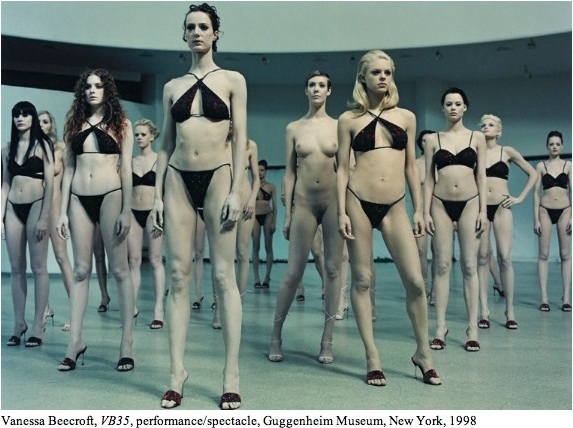

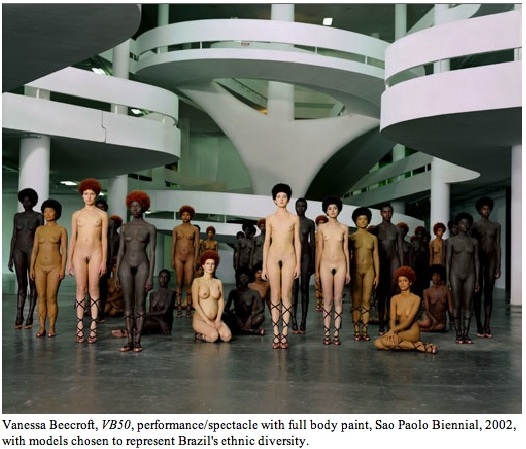

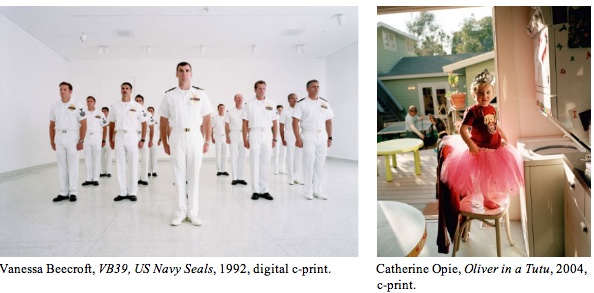

If Weems pictures the formative stage of the female homosocial, Vanessa Beecroft poses the stage at which the rituals of physical and cultural conformity slip in to condition a young woman's uniform of allure reinforced by her peers -- including when that uniform is comprised of nudity. Beecroft assembles large groups of nubile young women models, many of anorexic body size, in public performance settings. Whereas often they stand, sit, kneel and recline in one spot for hours, usually nude except for their various haute-coture accessories -- swimsuits, underwear, wigs, pumps, boots, panty hose, bras, makeup, and body paint -- Beecroft is obviously highlighting the relay of media-generated codification heaped onto contemporary young women by commercial and corporate interests to the extent of commodifying "women." Although Beecroft isn't focused on the historical precedents to the codification of young women's eroticism, she is no less underscoring the overarching context of women's homosocialization as a kind of ritual herding (or the au courant "trending") of sexual and gender uniformity common to adolescent and post-adolescent women regardless of locality and time.

But Beecroft is also visually analogizing a new dynamic underway in women's homosocialization. Whereas women's homosocial uniformity historically has an explicitly male sexual objective, the codification of women's sexual allure also implicitly relied on women's sexual wisdom -- a mix of complicity with men and the ingenuity, approval and often consensus of women. From the outset of her performances, Beecroft's modeling of the commercial coding heaped onto the XX-chromosome side of the homosocial divide raised the question, at what point does the desire of men and corporations cut through the intimate education of the girl child by her mother (portrayed by Weems) to the extent that women's enculturation is converted into women's sexual objectification and commodification? As a counterpoint, Beecroft also visualizes the homosocial reinforcement of non-feminist women by women, in facilitating the fantasies of men. And in so doing, the artist reveals that this appeal to men is actually an extension of the girlchild stage -- when a girl dresses, makes herself beautiful, for her mother, sisters and girlfriends. But the heterosexual woman doesn't simply convert her initial girlish desire to appeal to others of her sex into a desire to appeal to men. Even in developing her allure to men, the grown heterosexual women retains some aspect of her desire to secure women's approval -- and this is largely by remaining attractive to them. Beecroft, in effect, parades a new outgrowth of feminism whereby women openly and knowingly display and commodify their bodies for other women, whether as peers or as potential sexual partners.

To a lesser extent, Beecroft has also focused her scrutiny on the homosocial uniformity of men. Assembled and photographed on aircraft carriers or in stark white rooms wearing the uniforms of the armed forces, Beecroft's male models conform to the requirement of standing at attention in formations no less dehumanizing and taxing than those imposed on her women models. In a 2009 performance in Milan, city of Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, the most famous of all homosocial masterpieces, Beecroft staged a supper for twenty African-immigrant men dressed in stylish black suits and white shirts, a male uniform all its own, save that some of the men were shoeless as reminders of their origins. Perhaps the slight attention Beecroft pays to men's codes denotes that even in their uniformity, men exhibit the male continuum of codification (however objectionable to individual men) made by and for male habitation.

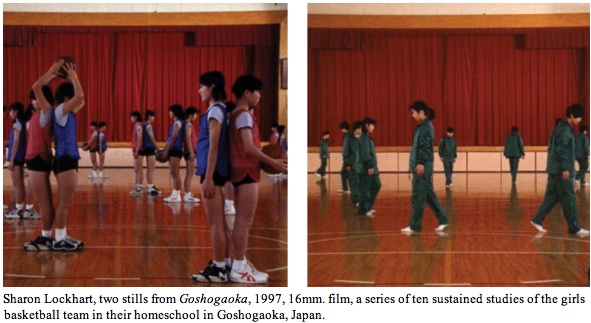

It is in the work of Sharon Lockhart and Catherine Opie that we see the seismic shifts away from the male homosocial codification of girls and women quite unambiguously. In Lockhart's film and photographs of a teenage girl's basketball team in a suburban middle school gymnasium in Goshogaoka, Japan, the artist heightens the viewer's awareness of the codes that female athletes adopt largely without regard to gender specificity as they enact warm-ups, exercise routines and cool-downs. The young women athletes are dressed for the sport and nothing else. In this regard Lockhart documents the most natural and lasting of homosocial shifts in a society that had, despite modernity, retained its traditional roles for women much more uniformly than the West. The gym has today become the iconic place in which mundane yet purposeful requirements in an individual woman's life are placed above the codification of fashion and gender issued by both traditional codes and elite tastemakers. Just as significantly, we find the traditional and intimate gender education conducted by mother seen with Weems has been replaced here by a coach, who could as well be a man or woman. Even the formalization of Lockhart's imagery opens the work to a larger questioning of what the homosocial context becomes for a new generation of women if not the lessons of old.

Lockhart's resultant imagery is the kind of recombinant gender codification that takes the coding once restricted to cross-dressing (Sand, Dietrich, Garbo) to what is now a true crossing of the homosocial divide, one that brands the athletic girlchild as a participant in the gradual erosion and usurpation of the male homosocial codes that were for decades most pronounced in athletic spaces. The message is salient and clear: by taking possession of the gender codes normally ascribed to male athletes, Lockhart's teenage girls are crossing the homosocial divide to claim the public space (as opposed to Weems' domestic space) and the team effort once confined to boys that stands in stark contrast to Beecrofts's passive, objectified, disconnected, and alienated female models.

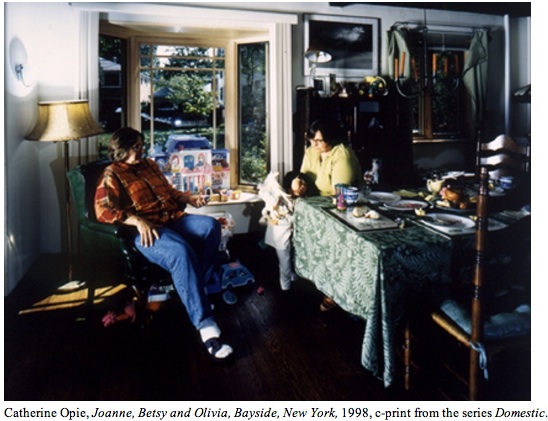

Catherine Opie's photographic series of lesbian families, which the artist shot as she drove across the continental United States in 1998, celebrates a homosocial independence that by its sexual and gender pairing represents all that is proscribed by America's conservative-Christian activists. Yet, in all their non-sexual domestic signage, Opie's photographs convey the family ideals such conservatives exalt. Seen in moments of intimacy, some posed, some spontaneous, we see the "personal is political" creed as much more than a 1970's mantra as it confronts the "Faith of Our Fathers" mentality, while at the same time embedding within its family structure. As common as is the familial and domestic tenor of Opie's series, the homosexual identity being redressed in traditional family codes remains a radical confrontation of homosocial and homosexual valuations, and one having few significantly Sapphic precedents in the art history presided over by male homosocialization (save a relative few surviving painted clay vessels from archaic and classical Greece, and even rarer pre-Christian Roman tomb stele commemorating women spouses), despite that lesbian sexuality crops up over the past three millennia in myriad "titillating" male-sponsored forms.

This is the true mark of the female homosocial emancipated from patriarchal values and aesthetics: representing lesbians not as simply erotically defined, but equally if not predominantly as natural and life-affirming spouses and mothers. Yet, there is significant irony in not being able to identify by sight alone whether Opie's homosocial mothers are also homosexual, so long as the artist provocatively declines to render their sexuality graphically and typically. This is the first step toward obliterating discriminatory homosocial/homosexual referents. Were we not conscious of the artist's affinity with the Stonewall nation, we might read her women to be siblings, neighbors, even polygamist sister wives watching out for each other and each other's children -- they remain that close to conventional representations of the homosocial family cluster of the ages.

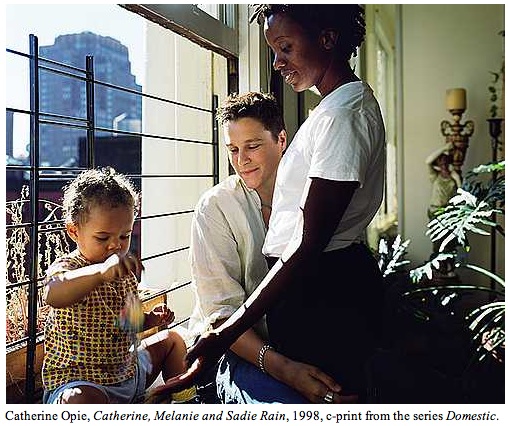

Opie also counters the conventional male homosocial code with her singularly iconic Oliver in a Tutu (and tiara!), a photograph of her young son crossing the homosocial divide of male dress and behavior with both unrestrained aplomb yet voidance of camp codification that but a few decades ago was made photographically de rigueur by Diane Arbus and other like-minded tourists into the then-underworld of transvestism and transexuality. Of course, as companion photos reveal, Oliver does have two mommies. Still, the context remains a scene of normalcy.

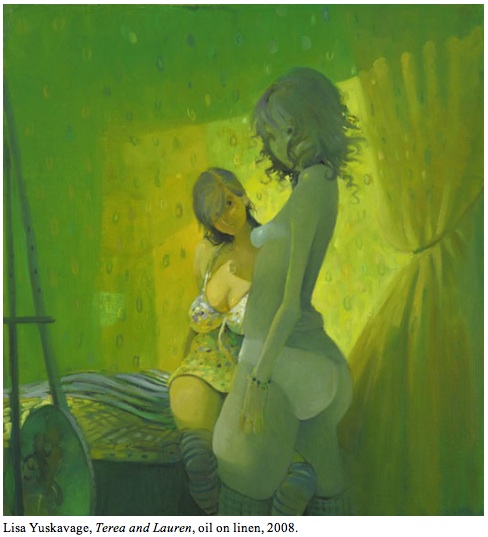

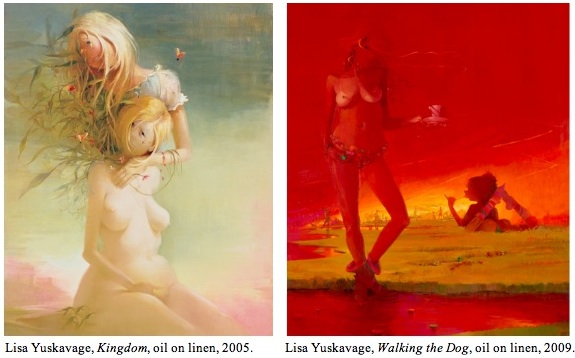

If Opie's lesbian families make us wonder what the world might be like if it were comprised only of women, Lisa Yuskavage's simultaneously lurid and lush "pets-of-the-month" paintings imagine what kind of graphic romance novels and soft porn calendars might entertain this world. It is redundant to say that Yuskavage's paintings are indicative of the ambivalence and contradictions facing women's individualist sexual politics. Purposely sentimental at the same time they are off-putting, cliched while challenging intellectual and artistic standards, Yuskavage embodies so many of the deliberate semiotics of the art historical and media "kitsch" in one simulated-adolescent imagining of a lesbian planet that even deciding whether or not the maker and fans of such work are feminist or retro-feminine invites prolonged debate. But in terms of mapping homosocialities, Yuskavage's fusing of the hetero-male and lesbian homosocial erotic iconographies gives her paintings the allure of women's empowerment derived from their seizure, repackaging, and recontextualization of the male pin-up and art history (Fragonard, Boucher, Tolouse-Lautrec). And all the while they remain on course in defying the commercial codes that once arbitrarily kept the homosocialization of male and female codes separate and distinct.

What is undeniable is that Yuskavage does it all for her own ironic, creative, aesthetic and erotic advantage, something she could never have done without feminism's advancement of women's control over their own cultural homosocialization. We might complain the artist is squandering feminism's gains on a regurgitation of "kitsch" imagery while questioning her purported expansion of women's cultural liberty. Or we might wax cynically about thrusting pungently prurient satire onto intellectual lesbian stereotypes of lesbians. But it isn't for any one critic to proclaim the worth of Yuskavage's efforts for women as a whole. Better we consider to what degree women's homosocialization is being shaped by populist and commercial assimilations -- as Camille Paglia considers the normalizing influence of Madonna and Lady Gaga, or Donna Haraway embraces the transformative power of Hollywood horror and sci-fi genres. Yuskavage's soft porn scavenging is a similarly strategic redefinition of popular iconography by women artists whose greatest impact comes with an awareness of the power that artists have to displace and convert the arbitrary homosocialization of gender and sexuality too long falsely advanced as the "biological determinism" of Nature on both the patriarchal and feminist sides of the divide.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.