When the Declaration of Independence was drafted on July 4, 1776, religious practice in the 13 colonies of the United States was colorful and varied. The quest for independence -- as well as loyalist resistance to the cause -- permeated church life and teachings across denominational lines. Patriots argued that their fight was God-ordained, while many Anglican clergy were bound by oath to pray for the King and the royal family.

Benjamin Franklin depicts God's role in the revolution in his design for the Great Seal of the United States. Circling an image of Moses parting the Red Sea and leading the Israelites out of Egypt is the inscription, "Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God." Cast in 1752 in Philadelphia, the Liberty Bell bears the words of Lev. 25:10, "Proclaim liberty throughout the land unto all inhabitants thereof." And the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence cite God as the author of the quest for freedom: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

Around the time of the Revolutionary War, most American Christians belonged to Anglican, Congregationalist, or Presbyterian groups. In 1776, there were also around 2,000 Jews (mostly Sephardic) and five synagogues in the colonies. The average size of a church congregation was around seventy-five members, and religious adherence amounted to only 17 percent of the total population.

The effect of the struggle for independence on religious practice was most visible in Anglican parishes. Since Anglican priests pledged loyalty to the King as a part of their ordination vows, many remained faithful to the British and continued with liturgical prayers for the monarchy. Boston's King's Chapel was a thriving Anglican congregation during this time, with "box pews," or small enclosures owned and even decorated by wealthy families, on the main floor, and "unboxed pews" for black or poor church members on the second floor. King's Chapel was the first church in New England to incorporate music into its services, having both a choir and an organ. Popular at the time was the hymn, "Old 100th," commonly sung today as a doxology ("Praise God from whom all blessings flow").

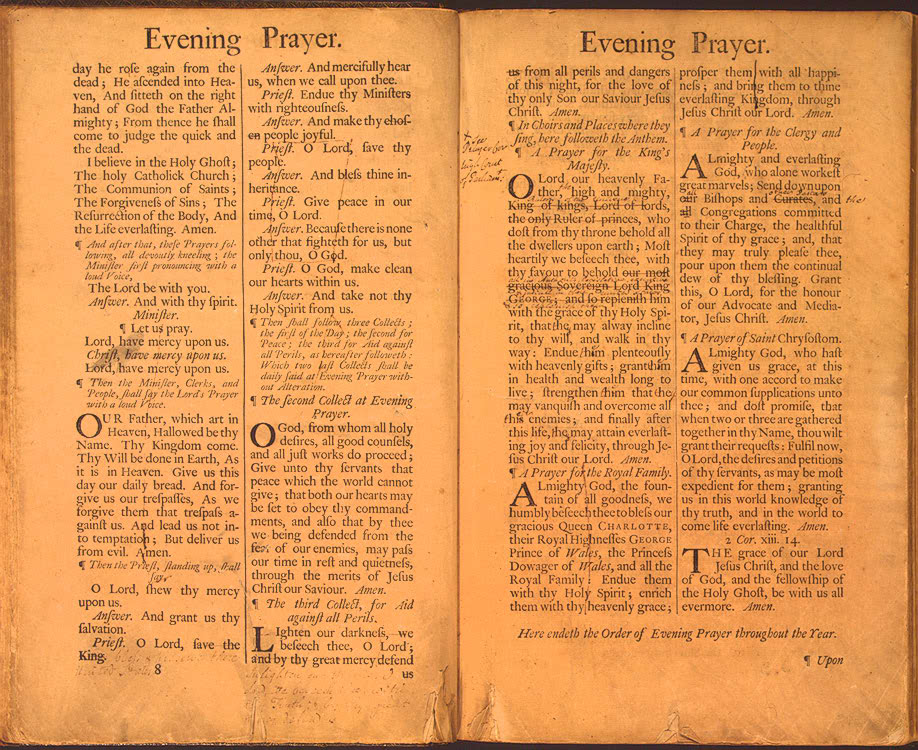

Led by a Loyalist priest, King's Chapel closed its doors after the British retreat on Evacuation Day (March 17, 1776) rather than allow the patriots to take over. Other Anglican congregations aligned themselves with the revolutionary cause and chose to change the liturgy rather than abandon it entirely. The rector of Christ Church in St. Mary's County, Maryland, pasted strips of paper with prayers for the Continental Congress over the prayers for the King in the Book of Common Prayer. At a vestry meeting on July 4, 1776, Philadelphia's Christ Church made a similar move, replacing the prayers for the King with a prayer for the wisdom of the new government: "That it may please thee to endue the Congress of the United States & all others in Authority, legislative, executive, & judicial with grace, wisdom & understanding, to execute Justice and to maintain Truth."

Rev. Peter Muhlenberg made a bold display of patriotism before his Anglican congregation in Woodstock, Va. At the conclusion of a sermon in January 1776, he threw off his clerical robes to reveal his Virginia military uniform. During the struggle for independence, a number of ministers left their congregations to work as chaplains or take up arms, even some Quakers who felt that the cause of independence superseded their commitment to pacifism.

The energy of the Great Awakening of the 1740s infused many colonial congregations with evangelical and prophetic zeal. This general spirit contributed to a great sharing of ideas and worship practices among Protestant demonimations. In Congregational churches, extended sermons were the centerpiece of worship. At the First Congregational Church in Greenwich, Connecticut, for example, the pastor used an hourglass to time his sermons. "Sometimes the sermons required three or four turns of the hourglass," reports Pat Larrabee, head of the church's Historical Committee. "And if church members fell asleep during the sermon, someone would tickle them with a feather at the end of a long pole!"

Sleepy congregants were less of a problem at Beneficent Congregational Church in Providence, Rhode Island. As a "New Light" church, the congregation embraced more emotional preaching typical of Jonathan Edwards and the revivals of the day. "Beneficent was definitely on board with the whole independence movement," reports Rev. Todd Grant Yonkman, Beneficent's current co-minister. "Sermons were very expressive and enthusiastic -- a little bit of fire, a little bit of brimstone. Not quite as staid and somber as the sister church across the river." In these churches, communion was celebrated infrequently and considered a special occasion.

Music played an important role in these early Congregationalist services, but most likely without instruments. Rather, church members would learn songs by repetition, or "line singing," in which a leader would sing a line and the group would repeat until a song was mastered. Popular at the time were the hymns of Isaac Watts, including "O God, Our Help in Ages Past" and "Joy to the Word." Legend has it that when they ran out of proper wadding for their guns, revolutionary soldiers once even used pages from Isaac Watts hymnals offered by a resourceful Presbyterian minister nearby!

The fight for independence took the energy and attention of church leaders and congregants, and the idea that God was on the side of the revolution informed both the religious and political mindset of the time. While religious practices were diverse -- from Presbyterian communion tokens to whitewashed Congregational meeting houses to Anglican redactions of the Book of Common Prayer -- both patriots and loyalists understood their causes to be ordained by God. Even today, "America the Beautiful" occupies a place in most church hymnals, while the American flag often stands behind the altar. And on September 14, 2001, mourners at the National Cathedral processed to Isaac Watts's hymn, "O God, Our Help in Ages Past." Two-hundred-thirty-seven years after the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, American belief in -- or hope for -- God's presence in the political realm lives on.