Their names are now just footnotes in the history of American motorsports: Jim Davis. Gene Walker. Fred Ludlow. Albert "Shrimp" Burns. Ralph Hepburn. Ray Weishaar. They were young men from farms and small towns who earned fleeting fame in the early decades of the 20th century by riding motorcycles around banked wooden tracks at speeds exceeding 100 miles an hour. They thrilled the large crowds that turned out to watch, and why not? It was time when Tin Lizzies still shared dirt roads with horses. When people went to see those boys whipping around the tracks, faster than anything they'd ever seen before, they were looking into the future. They were falling in love with speed.

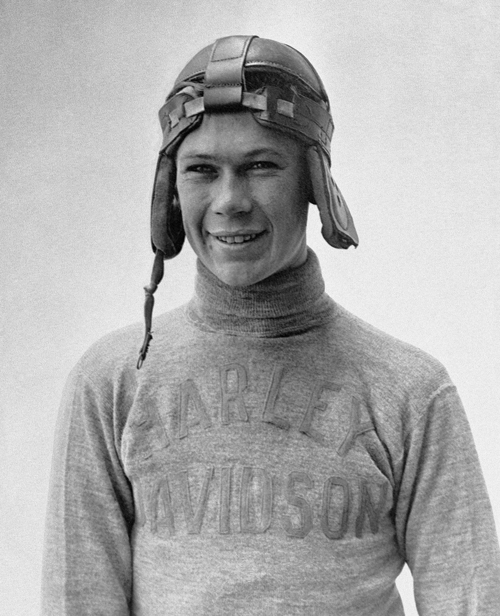

Board-track racer Arthur Mitchell, from the A.F. Van Order Collection

The era of board-track motorcycle racing was a fascinating piece of American history, as I learned while researching a story that appears in the April issue of Smithsonian magazine. The first mass-produced American motorcycle, the Indian, appeared in 1901; it was followed in 1903 by the Harley-Davidson. Less than a decade later those storied brand names, along with other companies, were fielding teams of riders who competed against each other in large tracks built especially for motorcycle racing. A promoter named Jack Prince put up the first tracks in Los Angeles--one would eventually be built on the site now occupied by the Beverly Wilshire Hotel--but soon they were being built all over country, from Denver to Sheepshead Bay, Long Island.

The tracks, called motordromes, were made of rough-cut lumber and banked steeply--sometimes more than 60 degrees. The early racing motorcycles were essentially bicycles with powerful engines but no brakes. Collisions and crashes occurred regularly; often, riders would be upended when their bikes hit 2x4s that had become worn or warped. What followed was terrible: ghastly injuries from hundreds of splinters, deaths from cracked skulls. Shrimp Burns, one of the most popular riders, died in 1921 after crashing at a track in Ohio. Ray Weishaar, who rode for Harley-Davidson's "Wrecking Crew" team, died in 1924 after dueling with Gene Walker, who rode Indians, during a race in Los Angeles. Walker died just two months later on a track in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania.

My piece for Smithsonian focuses on a photographer who documented the board-track era. A.F.Van Order grew up in Illinois, where he worked in his family's livery business. Apparently he got his fill of hooves and harnesses, because in 1907, when he was 21 years old, he bought a Wagner motorcycle and set about changing his life. He moved to Southern California so he could ride year round and compete in races. After an accident, he quit racing; to feed his obsession, he bought a camera and started taking some remarkable pictures.

Rider Harry Crandall

Charles Falco, professor of optical sciences and physics at the University of Arizona and the co-curator of "The Art of the Motorcycle," an immensely popular exhibition that opened at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1998, is an admirer of Van Order's pictures. "Photography is great for documenting things like this, and great photography is better than just snapshots. And Van Order was much better than just a snapshot photographer," he told me. Van Order's primary goal as a photographer was to preserve and memorialize, but his pictures go further, as documentary photographs so often do. In the blurred action shots, and especially in the portraits of riders--all smiles and confidence--an irresistible narrative emerges. The young men seem satisfied, if not happy, to have traded horses for horsepower; the danger that came along in the deal was something that they, and the rest of society, were more than eager to accept, even as the carnage at the tracks became appalling.

An early action shot

On September 8, 1912, Eddie Hasha, a.k.a. "the Texas Cyclone," was competing in the final event of the day at a motordome in Newark, New Jersey--a five-mile race against five other riders--when disaster struck. Hasha began the race in the lead, but in the third lap the engine on his bike developed a misfire. Another rider sped by him. Hasha dropped one hand from the handlebar, adjusted the engine, and quickly picked up speed. In the next instant he shot up the banked track and struck a rail at the top, along with a number of spectators looking down into the bowl from above. The number of dead varies from four to six, depending on the account. Hasha ended up hitting a post and being thrown to his death among the spectators. The press began referring to motordromes as "murderdromes."

By the early 1920s, local governments began to crack down, closing tracks, and the motorcycle companies that sponsored teams began instituting rules to limit speeds. But the public had grown weary of the sport. There had been a World War--another, far greater spectacle of death, in the meantime--and by the end of the decade board-track racing was a thing of the past. The 20th century was well underway.