DJ Ramses Cordova and Bishop perform on September 7, after their panel discussion on Music and Remix at Museum of El Chopo

Remix culture has been the subject of conferences and cultural events around the world for some time now. The term was introduced during the early/mid 1990s, and was popularized in large part due to the writings of Lawrence Lessig and the activities of Creative Commons, a non-profit organization that promotes the open sharing of knowledge and creativity. Recently I was able to participate in Bastard Pop: Cultural Recycling, a four day conference which took place at The Museum El Chopo in Mexico City, from September fifth to the eighth. The gathering included a series of presentations by scholars, researchers, artists along with DJs and experimental musicians. There is a video archive of all events, which are only in Spanish.

What follows are highlights of moments from the conference along with links and resources that were mentioned and discussed during the four days.

The conference was opened with commentaries by the organizers Jose Luis Paredes Pacho, Ruben Lopez Cano, and Julian Woodside. Pacho gave a brief contextualization on how recycling and remixing have long been important elements in the culture of Mexico City. Woodside invited the audience to consider remixing as a natural act that is part of culture, and encouraged everyone to consider the four day gathering as a space in which to share and debate questions rather than find concrete answers.

Lopez Cano in his opening remarks said that the act of remixing is a natural element in culture and that we should embrace it to make the most of our increasingly networked reality, clearly linking the motivations behind the conference with concerns of global communication and creativity.

The subjects of discussion after the opening day ranged from the now well-known conflict of openly sharing intellectual property vs. copyright infringement to questions on how the actual creative process is constantly changing due to the emergence of technology that encourages and makes extremely easy the production of new material with the re-implementation of pre-existing sources.

On Friday, a panel on literature and remix, which included scholar Ana Elena González Treviño, artist and editor Ximena Pérez Grobet, artist and journalist Cinthya García Leyva, and artist, writer Verónica Gerber Bicecci, along with UNAM scholar Susana González focused in part on the participant's' own literary productions that clearly questioned the concept of authorship. Gerber Bidecci, for instance, presented several of her works including a poem, which consisted of the negative space of an actual poem written by artist Mathias Goeritz in a language he invented. Another work mentioned by the panelists which stood out is the Pulitzer Remix, which consists of remixes of poems by 85 poets who received the Pulitzer prize.

Honest Trailers -- The Dark Knight Rises (Feat. RedLetterMedia)

The next panel focused on remix and audiovisual culture. The participants included researchers Rodrigo Bazán Bonfil, Rodrigo Pérez-Grovas, Ernesto Sandoval and José Hernández. Some of the resources discussed worth of note include "Bowie A Space Oddity," an alternate music score consisting of remixes of David Bowie recordings for Kubrick's 2001 A Space Odyssey. A lively discussion also ensued around mashups as forms of criticism; within this context various Screen Junkies remixes were presented, including The Dark Knight Rises and Breaking Bad. Though not mashups in the technical sense, these works clearly remix film and TV footage with clever voiceovers by a narrator that exposes the inconsistencies viewers are willing to ignore in order to enjoy the stories.

Honest Traliers -- Breaking Bad

The Shining Recut

The Shining Recut was also discussed but this one, unlike the other two, creates an alternate comedic reading on Kubrick's The Shining.

The last panel on Friday focused on music and remix. It included UNAM Philosopher and musician Dr. XL, DJ Ramsés Córdova, Music Critic Rafa Villegas, and music performer/producer Luis Bishop Murillo (UCSJ). This panel spent much of its time discussing the way sampling is data-mined online. Ramses Cordova in particular shared two websites that map out clearly and systematically how samples are used in music recordings. The first is Who Sampled. On this site, it is possible to see whether a song was sampled or uses samples of other songs. For instance, "Wanna Be Starting Something" by Michael Jackson uses a sample from Many Dubangu's "Soul Makoosa," and Jackson's composition in turn was sampled by Rhianna for "Don't Stop The Music." The second site Ramses Cordova shared is Tuneglue. On this site, searches on music artists give results with a minimal interface of small record-like icons. It appears that the possibilities are limited to names of artists at the moment. No song reference are available as of this writing.

Dr. XL discusses the sameness in sampling

Dr. XL closed the panel with a claim that humans after all are not so creative, because a large number of samples are taken from the same sources. For his argument he relied on a paper published by Nicholas J Brian and J Wang, titled "Musical Influence Network Analysis and Rank of Sample-Based Music" which demonstrates that even to this day much sampling is from funk and R & B of the seventies. Dr. XL's conclusion led to much debate after his presentation, to the point that George Yudice included a commentary as part of his own presentation the following day.

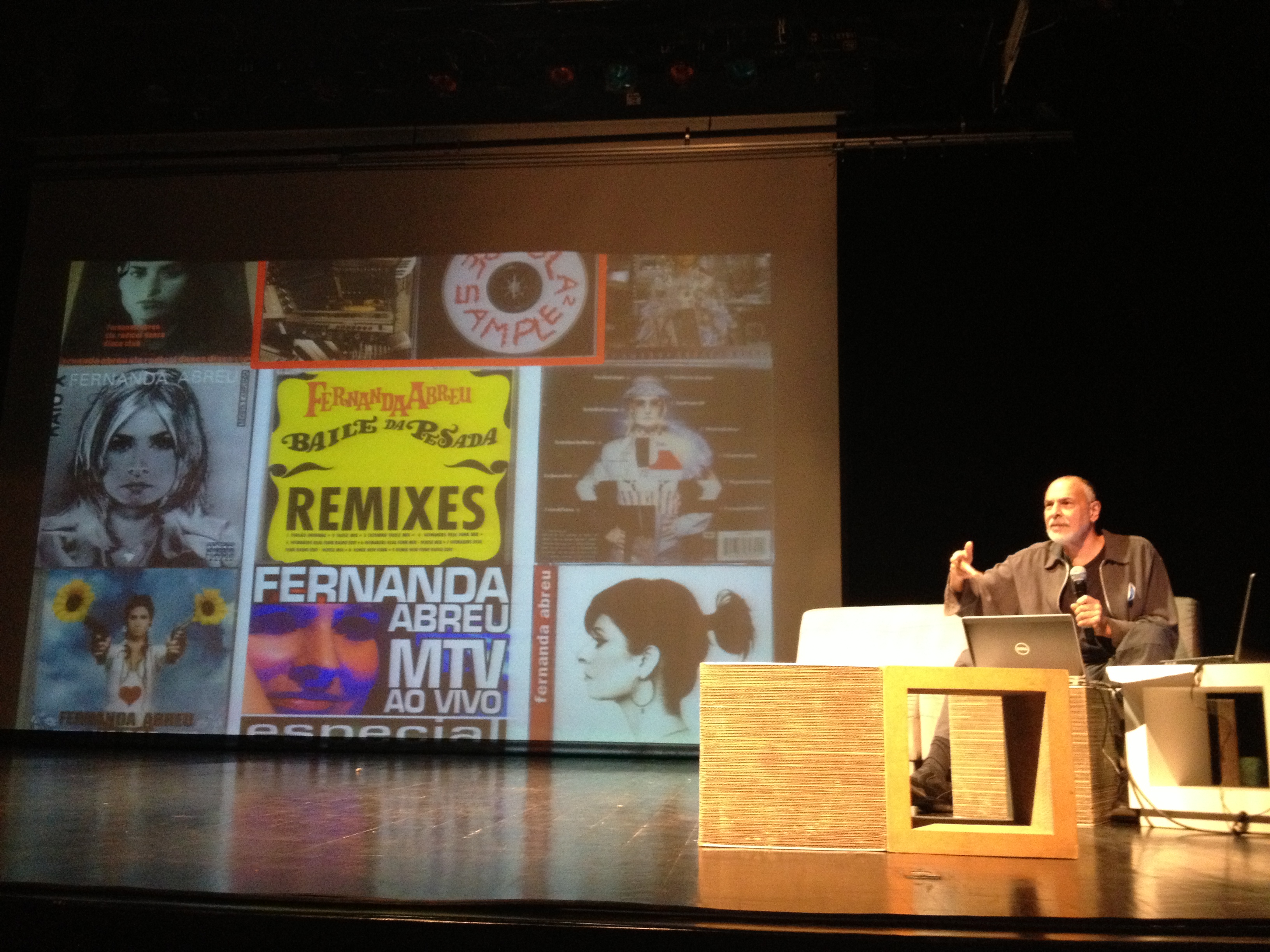

George Yudice during his conference on September 8, 2013, at The Museum of El Chopo, Mexico City.

On Saturday, Professor George Yudice, Chair at The Department of Modern Languages and Literatures at the University of Miami, presented his research on sampling and remix in Brazilian culture, with some brief notes on the music culture of Peru. The range of material covered was quite vast. Yudice's presentation focused on the relation of established recording artists such as Fernanda Abreu with songs such as "Baile de Pesada" to the act of legal and illegal appropriation of material in Brazilian culture.

Fernanda Abreu -- "Baile da Pesada"

Yudice's interest is in the role of intermediators, that is, people who are able to give the working classes greater exposure. This is of importance to him because working individuals otherwise may not have the ability to gain much visibility or a voice outside of their immediate reality. His last notes were on the DJs in the favelas, who appropriated funk and hip-hop sounds to develop their own versions for local giant sound systems. Favela DJs, as Yudice demonstrated, create a street sound that is unique to the culture of Brazil. This localized activity shares similarities with the early sound systems in Kingston, Jamaica, which began to flourish during the mid-1960s.

Three issues lingered in my mind after all the discussions. The first is just how creative we may or may not be. A possibility worth considering is that being a creative or critical person has always relied on reinterpreting material that is already well established in culture. This may be in part the reason why Dr. XL concluded that we are not very creative in the end if we recycle the same samples. But this argument presumes that creativity equals the use or implementation of diverse and perhaps even disparate sources that have little or nothing to do with each other. In this regard, we should remember that we learn by mimicking; we reference or reuse material and knowledge that has proven to be reliable and worth sharing, as well as material that is clearly designed to be repeated in order to sell the consumer something. So, to assume that to reuse the same sources leads to little creativity ultimately overshadows the fact that through the reinterpretation of the same material we are able to create truly diverse works that offer very different experiences -- that is if we are critically aware of such process and not simply participate to consume what is repeated for us in adds across media. Viewing the patterns of the same material being sampled without keeping this aspect of communication in mind is misleading for our understanding of creative processes.

The second issue is who gets to speak? This question was brought up during my discussion on the first day of events. I responded that people need to know when to speak, listen, and participate as part of a group or collective, but for this to happen we need to have education at the forefront of our future as a global collective. The third issue is how to deal with the transfer of knowledge among social groups? In this case, it was Yudice who presented a clear possibility when he discussed the importance of intermediators who are able to create links among social classes.

What became evident for all three issues throughout the conference is that current data-mining and mapping techniques when implemented to analyze remix culture make possible the understanding of how we may be recycling particular elements perhaps more than we realize. This awareness enables us to make conscious choices when looking for new material to reuse, or reinterpret. This is the emerging potential of remixing in a networked culture in which individuals who formed part of the Bastard Pop events at The Museum El Chopo appear to be invested. Indeed these and other issues discussed are not only of local but of global concern.

The creative challenges such awareness offers are likely to become more pronounced and grow intensively as the necessity to revise copyright laws turns unavoidable in order to live up to the creative potential of networked communication.