The two-part exhibition, Bill Traylor: Drawings from the Collections of the High Museum of Art and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, and, Traylor In Motion: Wonders from New York Collections, is on view at The American Folk Art Museum in New York through September 22. For further information, visit the American Folk Art Museum website.

After four hundred years of slavery in America, we can name but one slave-become-artist who bequeathed the American public a sizable body of art. Bill Traylor is his name, and his drawings appear to be largely optimistic cartoons--sketch art ranging from the humorous to the serious, the light-hearted to the socially-significant. But the history of the artist who came into the world as an Alabama slave, remained on the plantation of his birth as an emancipated sharecropper for six decades, reared 25 children in abject poverty, and only in his mid-eighties turned to art-making without training or presumed ambition, together suggests that the drawings he made at their core embody a more deeply affecting archetypal art. The kind of art affording Americans, and in the universal sense audiences around the world, something approaching a collective catharsis for the historical and ongoing crimes of human slavery and exploitation. At least that catharsis is potentially offered us once we free Traylor's work from the denigrating status of "Outsider Art" with which the present-day art market has saddled it, and which persists in diminishing Traylor's import both as an artist and as an historically significant person of color.

Bill Traylor, born a slave in 1854 and died a free man in 1949--or as much as he was free to do what his race and poverty allowed him--has been somewhat hyperbolically called the finest draftsman of his generation, an artist whose powers of invention rival those of Picasso and Matisse. Whether we regard such exclamations with skepticism or assent, the opinion contrasts starkly with the reality that few people even in the U.S. artworld knew Traylor's name or his work until very recently because of institutional neglect. Racism and poverty have been the obvious obstacles to Traylor's appreciation, but more recently it has been the myth of the Outsider Artist, a kind of cultural ghettoization of the so-called untrained, poorly connected, marginalized savant, that accounts for not just Traylor's relative obscurity, but for the obscurity of thousands of artists like him throughout the U.S. alone. Eurocentrism--the Western cultural bias that elevates the self-proclaimed refinement of the European art-historical legacy above the productions of the myriad non-Western legacies of the world--is an even more entrenched and insidious dynamic keeping Traylor from achieving the truly international renown he is due.

This is despite that the Outsider Art identity has in recent years assumed a kind of perversely glamorous, badass status for its artists, along with the art dealers, curators and critics who advocate their work, while increasingly resisting the marginalization to which it was once relegated. Together the artists and their advocates have seized hold of the representation of the Outsider Artist to remake its myth into the equivalent of the antihero popularized in the mid-twentieth century by the literary, dramatic and cinematic artists who disdained the rigid traditions, customs and values defining the tastes of the bugeoning mainstream audiences.

But unlike most Outsider Artists, Traylor's childhood as a slave has imbued him with an historical significance that precedes estimation of his talents. For the last century, there was a considerable craving by African-American artists and their sympathizers for an art about slavery to fill the void made by the dearth of actual slave artists. Until American audiences came to appreciate Traylor, we had only the grandchildren of slaves to count on for crafting a woefully-late catharsis for the shame of American hatred, terror, and criminal handling of Africans and their American descendants. From the 1940s on, black artists in America came to represent a formidable historical memory and conscience for contemporary audiences both in terms of the perfection of their respective crafts, and in representing the legacy of slaves. In literature, we came to look to Toni Morrison, Alice Walker and Alex Haley; in dance to Katherine Dunham, Alvin Ailey, Judith Jameson and Bill T. Jones; in music to Bessie Smith, Ma Rainy, Billie Holiday, and B.B. King; in visual art to Jacob Lawrence, Elizabeth Catlett, Romare Bearden and Faith Ringold. Among such illustrious talent, Traylor stands as the only significantly recognized slave artist among them, which is why we should feel compelled to ask, Why hasn't Bill Traylor been honored as the singular National Treasure that he is?

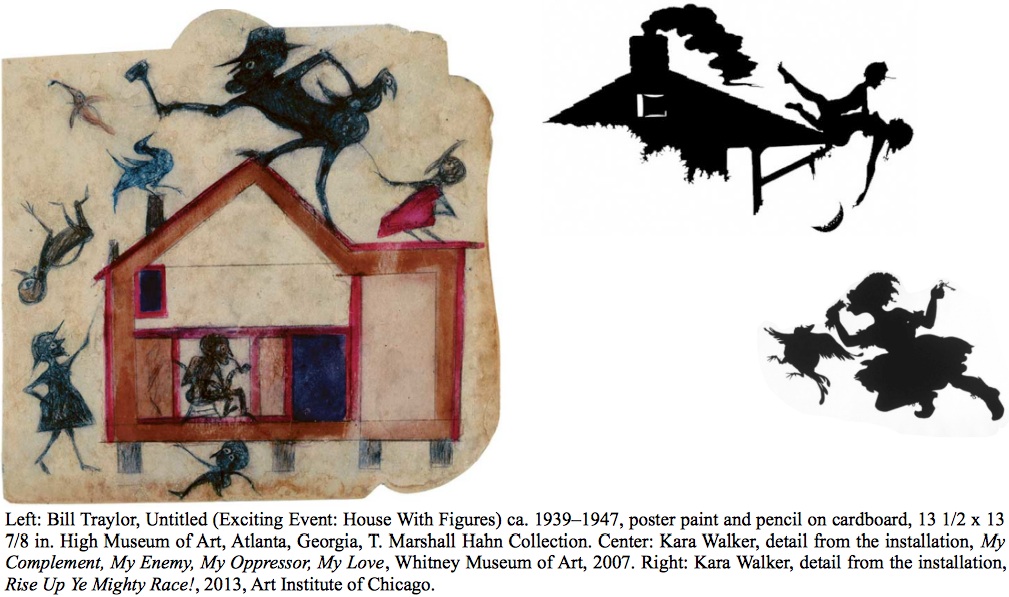

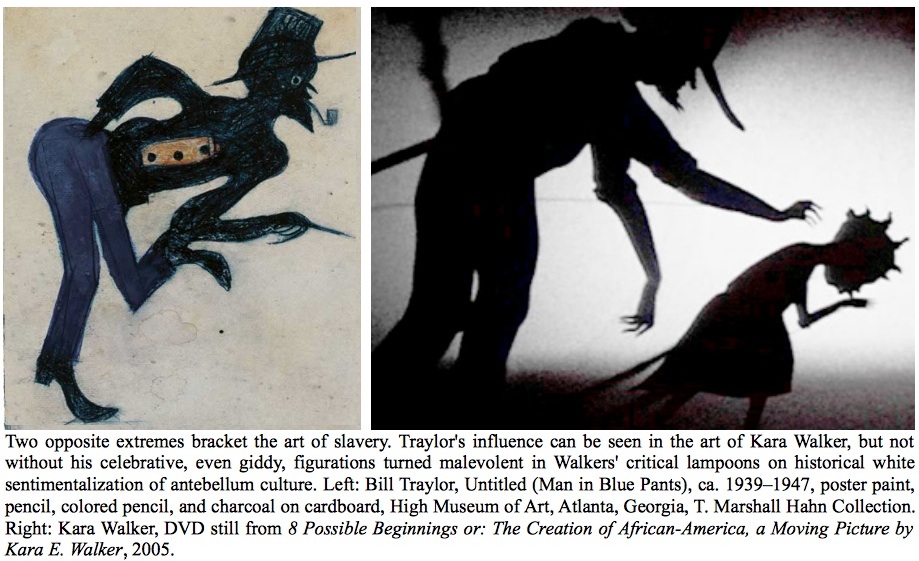

Traylor isn't the only visual artist born into slavery. Romare Bearden's and Harry Henderson's impeccably reseached book, A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present, names Scipio Moorhead and Harriet Powers. Unfortunately, little remains of their art to ponder, while it is the fortunately large surviving body of Traylor's drawings, along with his work's blindly gratuitous resemblance to modernist art brut, concurrently produced in Europe and America, that makes the neglect of Bill Traylor by art historians, critics, and the art-buying public loom large as an indictment of the unfortunate classification of Outsider Art, on the one hand. On the other hand, it indicates to what extent America remains a place where the history of slavery still casts a shameful shadow over even the liberal fight for equal representation under democracy. It's a neglect that reflects poorly even on the enclaves of the avant-garde--who have been quick to heap accolades on contemporary artist Kara Walker for making hugely elaborate installations lampooning the sentimentalization of antebellum slave culture in novels, drama, and the kitch pictures that for decades titillated white audiences.

Traylor, by contrast, showed neither interest in pictorial historicism nor political moralizing. Although it's true that Traylor knew the scourge of slavery only as a boy--he was nine when Lincoln read his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863--the sustained culture of segregation, prejudice and enforced poverty impressing upon Traylor, who came to have 25 children to support, and upon every former slave who freely chose to stay and work on the very plantations that once held them captive as share croppers, was no less an effect of slavery than the arrested wills of a people so long denied the liberty of choice. Besides being children of slaves, the sharecroppers performed much of the same drudgery as their slave forebears.

And yet we may regard the greatest misfortune to have befallen Traylor when, in his mid 80s, the sale of the plantation on which he spent his entire life was to be further denied him. The scene of his eviction offends our modern liberal sensibilities in its picture of a destitute and infirmed human being turned out to live, first on the streets of Montgomery, Alabama, and later among the caskets, replete with corpses, of the mortuary where Traylor was finally granted the charity of shelter.

That it was only as he neared his final demise that Traylor began making art from discarded cardboard and whatever marking medium he could at first salvage from the garbage of the street, indicates to what extent that art proved both a refuge and a saving grace for even this most dispossessed of human beings. The power of art asserts itself in the chance encounter that attracted Charles Shannon to Traylor's work. Shannon, a white painter trained as a modernist, came to Montgomery after having received a fellowship to paint. As if the likelihood of Traylor being befriended by a well-off white man unafraid of the state's Jim Crow laws regarding interracial fraternization weren't in themselves slim, the chances were exceedingly slimmer that such a man would spend more than a moment studying the "scribblings" of an infirmed vagrant. Yet this is the way that history records their introduction. As the story is told, Shannon from the start recognized in Traylor's renderings the mark of a visionary he thought important enough to support financially, and whose donated art supplies encouraged Traylor to produce several cartoons a day.

Despite his life-long impoverishment and pronounced labor, Traylor's art betrays no sign of the bitter and sustained slavery of spirit that burdened so many former slaves and their descendants. We can count Traylor's propensity for good humor and his peaceful disposition for enduring the poverty he slipped back into when Shannon was drafted into the Second World War. But we might also regard the same good humor as facilitating the conscience of the white liberal collectors in offering no threat of indictment for the social injustices being perpetuated on blacks. Even today, Traylor's work may initially seem to offer no reason to dig beneath our perception of its benign significance in search of some hidden and darkly historical or racial significance that might one day emerge to bite us--and perhaps devalue the art as a result.

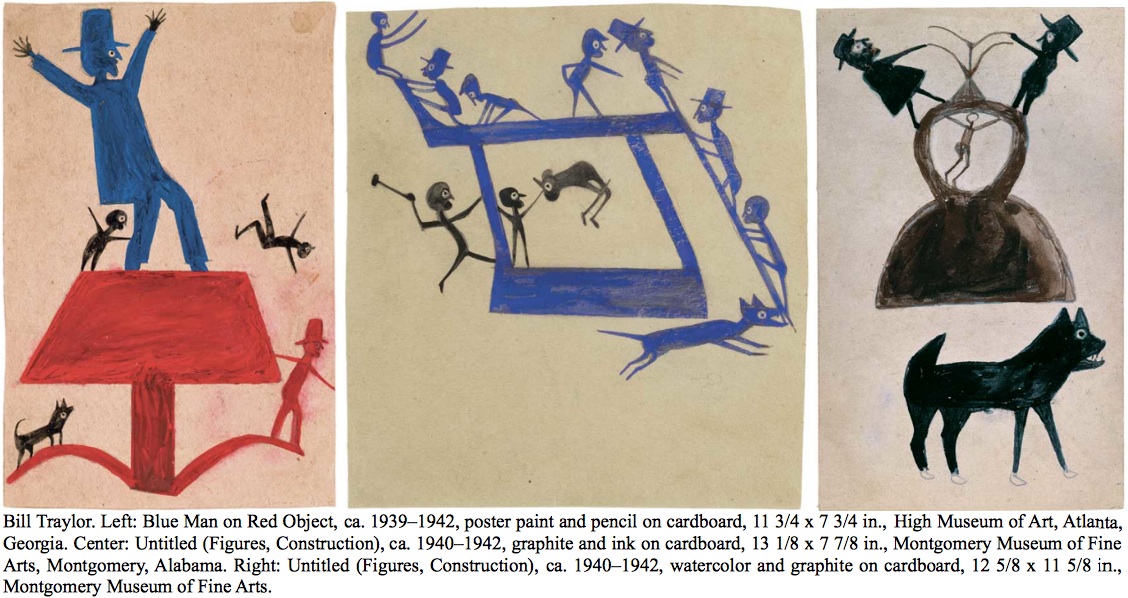

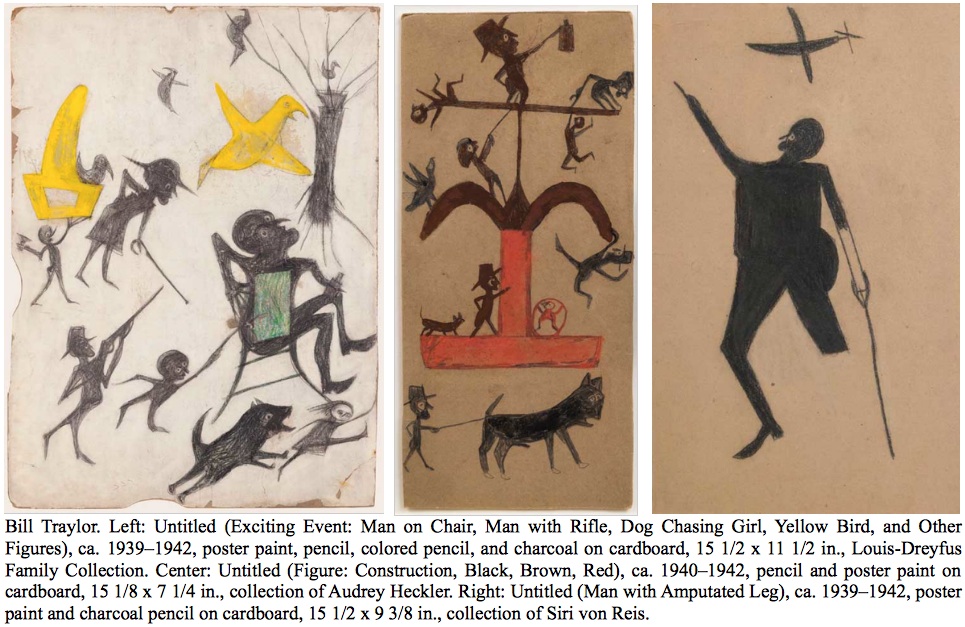

There is no denying that instead of an overt iconography of drudgery or racism, we're presented abbreviated glimpses of the rituals and period costumes of black Americans left to their own devices and faiths. Instead of indignant rage or dissent, which never would have been tolerated even by the more liberal whites of the day, Traylor's drawn and painted subjects exude a remarkable exuberance, the kind that thrives among tightly-knit families and networks of amiable friends however impoverished. His graphic world is comprised largely of the open outdoors, though it is an outdoors implied more by the movement of the people and animals busying themselves with work, ritual, and play than an envisioned landscape--there are rarely trees or shrubs, mountains or horizons. Animation might be said to be Traylor's unifying subject--animation of spirit as much as of the body in beiing unrestrained. It is this absence of restraints throughout Traylor's work as a whole that not only embues his work with optimism, but which as well retrospectively helps to set the standard for the tempered optimism we find marking the art of the generation of African-American artists active just prior to and after the Second World War. Besides Traylor's art, we find such optimism salient among the depictions of blacks migrating to the Industrial North, as well as the portrayals of Southern black sharecroppers, made by the better known and better assimilated artists, Jacob Lawrence and Elizabeth Catlett. Such optimism meets its end by the mid-1960s, when the Black Power movement instilled African-American art with the iconography of dissent and no small measure of racial cynicism aimed at the white suprematism that everywhere threatened the new and hard-won Civil Rights of black Americans.

Before casting a more penetrating light on Traylor's art, there is much merit to our consideration of the view that Traylor's art should stand alongside that of Lawrence and Catlett--artists whose racially motivated optimism have been attributed to inspiring the young Coretta Scott and Martin Luther King, Jr., among other prominent African-American Civil Rights leaders, to pursue careers in political activism. It is an optimism that persevered despite the harsh realities of racial prejudice in the U.S., and the backlash that came to follow Civil Rights legislation in the mid-1960s. Traylor may have had considerably less impact on the art of historical dissent propagated by Romare Bearden and Faith Ringold in the 1960s and 1970s, or on the generation of neo-conceptualists of the 1980s and 1990s, such as David Hammons, Rene Green, Fred Wilson and Gary Simmons, artists who preferred to employ an indignant irony in their art, one intent on equating art and in-your-face activism as a single act. Such artists deemed optimism anachronistic, if not apologetic to racism's perpetuation.

But this is 2013, and putting Traylor at the forefront of the mid-20th century African-American context for art today seems an act of reclamation that, in addition to restoring his place within the African-American artistic heritage, also dispels the unfortunate aura of Outsiderism that up until now arrested Traylor's impact, just as the myth of the Other, issued by eurocentric academics in America and Europe, and glamorized by white institutions and collections of art, kept scores of African-American artists from being accorded the same artistic legitimacy as white artists as late as the 1990s. It also helps us to keep more acutely aware of the natural progression of African-American art from its legacy in slavery to the measured optimism of the 1940s and 1950s, to the indignant art of the 1990s that dissed the Outsider and the Other myths as racist postulates posed in postmodern-theoretical drag.

All of this makes it seem a curious thing that the issues of slavery and its aftermath, and the African-American artistic heritage in particular, aren't made more central to the twin exhibitions mounted at The American Folk Art Museum this summer by curator Valérie Rousseau. Along with the Museum's Director, Anne-Imelda Radice, and several of the trustees I met there, Rousseau is vocal about rescuing Traylor from the neglect that befell him. To correct this neglect, Rousseau assembled 104 drawings and paintings, 60 of which were imported from Atlanta's High Museum of Art and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, and the rest from various New York collections. The installation, which keeps the collections essentially distinct, is modest by the necessity of the Museum's recent fiscal problems and relocation to a relatively small space across from Lincoln Center. There is little doubt the effort is a valiant attempt to bridge the aesthetic gaps gouged out by racism and its more insidiously entrenched aesthetic eurocentrisms. Unfortunately, the exhibition attempts this project with an ahistorical and politically neutral overview--which means that the Museum falls short of supplying the urgent requirement of placing Traylor in the larger ideological and cultural context of African-American art. The context is crucial not only because it helps to reinforce the untrained artist's status by explaining the cultural and economic disparities that necessitated it, but in showing to what extent the style of such an untrained artist can have a major impact on subsequent artistic productions.

While the American Folk Art Museum is eager to place Traylor and others like him in the same context shared by the schooled modernists whose similarly spare and ironically "primitive" renderings came to dominate the century, there seems to be little, if any, attempt made to point out that the seemingly formidable walls separating the Outsider from the avant-garde modernist is no more than a conceit based entirely on myths buttressed by an entrenched class and cultural eurocentrism--that is, an assumed preference for perpetuating the dominant view of the European aesthetic superiority. In isolating Traylor's largely optimistic and universally archetypal art from the larger African-American context to which it belongs, AFAM avoids the difficult issues of identifying the discreet proscriptions and prescriptions of race and class within the dominant white art institutions that keep the historical art of identity from messing up their "neat" classifications of art history and the social values they perpetuate, however divisive they may be.

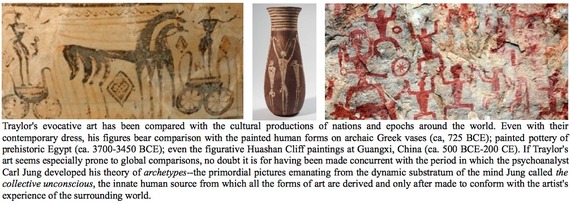

At least Rousseau and AFAM challenge audiences to see beyond Traylor's surface signification of naivete. In this, the installation's strategy rewards viewers with a virtual ballet of rapturous cartoons loaded with the vernacular signage of the Southern slave and sharecropper of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But Traylor's art also transcends such regional and temporal trappings by simultaneously evoking gratuitous comparison with the art of prior civilizations. Traylor's art brings immediately to mind the iconographies, and even the stylizations and mannerisms, that we witness in certain Greek, Egyptian, Arab, Persian and Paleolithic art. At the time that Traylor made such art, few art professionals were well read in the literature of Carl Jung's universal archetypes, a theoretical account of the continuities of image and form found among the global art and artifacts that Jung thought to be evidence of a neurological basis for cultural consciousness and identity. To say that the rest is history is to concede to Jung the victory of winning the world over to his view of a somatically-structural basis to cultural universality, which for many art viewers today, explains why an artist like Traylor, who neither visited nor, so far as we know, was exposed to what few art-historical prints circulated prior to the mid century. Today, Jung's theory is so widely understood that it seems near-unnecessary to remark that Traylor's powers of universal vision may be explained by his heightened capacity for rendering the archetypes of character, behavior and ritual that link him in terms of neurological predisposition and cultural aptitude with an array of artists throughout history and the world. Such a heightened, intutive recognition of universal form and its relationship to meaning-in-content is something that cannot be claimed of every artist, often not even among those we rank as most brilliant in their innovations, and certainly not of the many we regard to be untrained and unexposed to the unearthed global masterpieces of some forty millennia.

On the other hand, contextualizing Traylor's work, which means re-seeing it not as an instance of Outsiderism, but as a universalist forerunner of the 20th-century African-American diasporic art, not only works to unseat and discredit the notions of the Outsider and the Other that have maligned much art that is not eurocentric. It also brings the art of African-American dissent into deeper, richer contrast with the earlier art of African-American optimism that Traylor represents. With Traylor, optimism apparently greeted his "discovery" that a man like himself could not only become an artist after having lived eight decades, but to become one endowed with a glee, practicality, and socially-observant gaze. But whatever sophistications we attach to Traylor's vision, his work largely remains childlike--unconditionally direct and genuine--in its vision of the world around him. This likely includes a memory life experiences extending back to childhood that elderly people often recall, in Traylor's case such things as the barnyard ritualism of Lukumi (the African source for Santeria), as well as of Sunday-evangelicalism, go-to-church dandyism, neighborly barn building, and an iconography that correlates roughly, if idiosyncratically, with the speaking-in-tongues spiritual fervor that marks the theater of Pentecostalism.

The people busily building and chasing and climbing and waving in Traylor's compositions are immensely engaging and entertaining. But even such pedestrian motifs, when left without noted historical, racial and religious context, leave Traylor's art appearing as signifiers without signification. In short, without anchorage in the African-American context, Traylor's art is left to seem floating aimlessly in a cultural vacuum. We can understand and appreciate the simple fact that an artist deprived of an education and travel will return again and again to articulating the visual and formal remnants of his experience and unconscious valuation of life on the plantation where he grew up. But for a curator and museum intent on freeing the artist from the prejudice of Outsider status, the failure to anchor Traylor's work within the larger historical and political nature of the plantation, and to further buttress it with references to both contemporary and historical art that completes its implications for subsequent generations, is an invitation for a more enterprising and wealthier institution to fill the vacuum. For a museum striving to prove itself in a city filled with museums of international renown, this lack rates the Traylor exhibition as a missed opportunity, as rich and stimulating as it is visually.

If I belabor Traylor's history as a slave and sharecropper, and as an artist with affinities to other artists living and dead, it is because I believe his work is by no means devoid of the social and political coding of better trained artists. Traylor's experiences of race and class, his relative social immobility, inform the signage of his work--those features of a picture that convey information about the often hard-to-interpret, yet deeply embedded codes at work in a society, often unconsciously, yet no less shaping the dominant social behavior of the day. In short, the human and animal figures Traylor has drawn and painted, aren't merely cartoon ciphers telling a story. They also reflect the larger structural mesh of historical forces--those of communities, religion, and labor especially--that determine the balance of liberation and responsibility that the artist by all appearances believes to be necessary to keeping society and reality operating harmoniously within his compositions. To put it in the parlance of modern cultural and aesthetic terms, work such as Traylor's is telling us something about what the human beings at the bottom or the social rung do in the subjective realm of fantasy and dreams, the place where even the slave and the sharecropper reign supreme.

For those of us enamored with the contemporary artist, Kara Walker, and her stylized silhouettes critically evocative of the slave life we know through art and entertainment, the art of a real slave who tended the property he lived on as a sharecropper is humbling. The great fortune afforded by entrance into Traylor's fantasy world is that it is a benevolent place--the opposite of the malevolent place of Kara Walker, who is only imagining the life of a slave (however historically well-informed and personally empathic her imagination is). The sheer absence of color in Walker's sexually- and racially-charged installations contrasts radically with Traylor's varied colors. Yet within every line and colored field throbs a significance closer to the slave's reality than anything Walker could fathom. I say this because the significance of Traylor's optimism and childlike rendering EMBODY the slave's conditioning of forced consent, obedience, and ultimately the submission to complete repression.

In this revelation, we can reconsider the significance of Traylor's childlike cartoons and compositions to be found in what they do not show or tell--what would bring death to a black man in the South of the 1940s upon their utterance. But twenty more years made all the difference--as the radicals of the 1960s who sought Black Power taught us as they refused to act politely. Traylor, of course, had no recourse but to secure his existence by perpetuating his slave's conditioning at the expense of his struggle for recognition as a human being of equal dignity and intelligence. In other words, the lack of training that makes a grown man or woman resort to making childlike cartoons reveals not a desire to appear childlike and innocent, as suits the art brut artist. In Traylor's case, to appear childlike has a more profound meaning--that of survival--of flagging himself as unthreatening to a white world. The genius of Traylor is that of the savant who regresses insistently to childhood to escape persecution. In this sustained child realm he could discover himself through his art, while communicating to others, however unconsciously, the extent to which having lived as a child slave and as an adult sharecropper, forced him to remain a child out of the discipline of bigotry.

We see this with children who retreat into some deep space within themselves to escape the abuse of adults, often enforcing a permanent retreat through a life of mental illness. But Traylor was luckier than those children. He could as an adult assimilate into the world of his oppressors so long as he did not express the real conditions that pressed upon him. That is until he turned his inner experience of life inside out, which in the South of the Jim Crowe laws required that he assume the freedom and fantasy only allowed a perpetual child--though a child seeking to disguise the refuge where freedom rings out with seemingly harmless cartoons.

Traylor's recourse as an artist was to represent the traumas marking out his life. But he signified those traumas symbolically with the only signs he was allowed--those that wouldn't betray the conditioned slave's code of respect for the master. In this respect, Traylor's work suggests that even old age and the semblance of liberation are not enough to free a human being from the conditions of strife and repression that arrests human growth in all aspects of cultural life except the private recourse to freedom found forever in dreaming.

If Valérie Rousseau and the Folk Art Museum provide us any insight to the politics attached to Traylor's production of untrained style and signage, it is in the discreetly embedded yet existential sense of recognizing an art whose deceptively childlike significance represents a grown man's acceptance to the submission forced on him by a hostile world. This is what Albert Camus considered the individual's meditation on the absurdity that greets the human will for freedom with pronounced indifference, if not formidable obstacles. We as free individuals might prefer--as Camus did, as Kara Walker does, and as Traylor seems to have not--the rebel who resists the social face of the absurd--the human force that under tyranny requires us to abandon our dreams to the dictates of subservience and drudgery. But we might also recognize that Traylor, at the end of his life, resorted to, if to not a commitment to art, certainly to a commitment to the self-satisfaction knowable through self expression. In this manner, Traylor, by life's end, was offering himself, and perhaps whatever audience he might have imagined and yearned to be sympathetic to him, the only kind of resistance to power and repression that a 95-year-old black man in Alabama could offer some eight decades after the Civil War's end. That resistance is the art of insistent optimism and celebration of humanity and nature that can be summoned even amid the most sustained coercion.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.