Have you ever had your heart broken? Has a lover left you abandoned, adrift, forsaken?

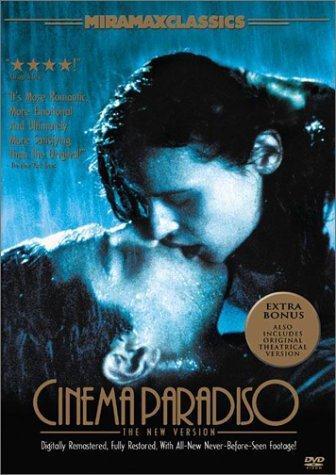

I was reminded of my own broken heart when I watched, for the second time and after many years, the 1988 Oscar-winning film Cinema Paradiso. The first time, I watched it as a moviegoer. This time, I watched it as a student, for a course I'm taking called "Quests for Wisdom: Religious, Moral and Aesthetic Experiences in the Art of Living" here at Harvard.

When I watched the film years ago, I found it heartbreakingly beautiful. The theme song, composed by Ennio Morricone, is the sound of tears falling. On my iPhone I have recordings of Josh Groban singing it and Chris Botti playing it. But what could be better than the famed composer himself conducting?

The second time around, I still found it heartbreakingly beautiful.

In the opening of the film, a middle-aged man arrives home to his palatial apartment in Rome very late, with apologies for waking his girlfriend. She tells him his mother called with news of a death. It's his old friend Alfredo. The middle-aged man is Salvatore De Vita, a famous film director, and he spends the rest of the night sleepless, turned away from his partner, eyes open, remembering...

We see him as the mischievous boy, Totò, in the tiny Sicilian village of Giancaldo where he grew up. We go back to the years right after World War II when his father is delayed -- as it turns out, forever -- from returning home. Totò has only his sorrowful mother and his young sister, who aren't up to keeping the boy in check. The village has a movie theater in the central plaza called Cinema Paradiso. Alfredo is the projectionist, and he can't seem to get little Totò out from under his feet in the projection room.

Among Alfredo's duties is to excise all romantic kissing scenes from the movies, per the direction of the local priest. Totò, seeing some of the offending scenes while lurking in the theater, asks the impatient Alfredo for the cut-out sections. Alfredo refuses, saying he must splice the scenes back in before returning the films, but finally seems to relent. "I'll give them to you if you promise never to come back," he says.

Later, little Totò is transformed into the dashing teen Salvatore, who takes up a home movie camera and spots a lovely young woman named Elena. He falls in love, and after at first failing to win her, through great dedication and suffering, does finally prevail, and the two enjoy the paradise of young love.

But her father intervenes and takes Elena away. The two lovers plan a rendezvous, but Elena misses it. Salvatore is devastated. Alfredo advises him to leave Giancaldo forever. "Forget the girl," he says. "Forget this place; there is nothing here for you. Go and never return. Don't write. Don't call. I don't want to hear from you ever again. I only want to hear others talking about you."

At the train station, Salvatore gives his mother and sister desperate embraces and finally says goodbye to Alfredo, who gives him some extra advice. "Whatever you do, do it with the same passion you had in the projection room." Then Alfredo pushes Salvatore away.

***

Dashed love

It's 1970 and I am 15 years old. I'm in high school in San Diego and fall desperately in love with a beautiful girl named Valerie. She plays clarinet in band (where I play trumpet) and piano as well. I walk her to her grandmother's house where she lives, and carry her bags. Valerie has a radiant face with a small mole on her cheek, which in my mind only adds to her loveliness. How suddenly perfect it feels to put the palm of my hand on her narrow waist as we walk. Her lips when they touch mine make my mind sigh with relief, as my thoughts fly away, like flushed birds, from the shotgun power of her kiss.

I walk the streets alone at night with my almost-manly vigor, no rain, no cold, no dark keeping me from rushing to her smile. Where before they were only parked cars and lawns and front doors, now there is beauty everywhere I look. Everyone I meet is wonderful or witty or hilariously quaint.

Then Valerie leaves me for the drum major.

He is a senior and much admired, a talented musician and manly figure in his Black Watch Guard uniform, marching in front of our band and directing us. I am an ordinary trumpeter, a lowly soldier. She won't return my calls and my desperate letters go unanswered. I now walk the streets of my neighborhood at night with a black heart. All that I see is dreary and hopeless. I imagine tragic forms of death for myself that at least might cause her inconsolable regret. An auto accident? Pulled out to sea by sharks? Only my high school ring found on the beach, its green-faceted stone scuffed from the surf. Crying uncontrollably, she slides my damaged ring back on her necklace...

Adults are quick to dismiss the lovesickness of teens. Have we have forgotten how intense it can be? Romeo and Juliet are ever ready to remind us, and Shakespeare made them hardly older than children. Do teens tap into some elemental power -- for joy and for pain -- that we elders can no longer feel through the cataracts encasing our hearts?

Do we ever really recover from our first heartache? Did Salvatore move on from his Elena? His mother, when he finally returns, says she never hears any love in the voices of the women who answer his phone. Is this because Salvatore can't really love them?

But, perhaps he uses his pain in his art. Perhaps his angst helps him as a director to shoot those perfect scenes, and make those perfect cuts that separate the good from the great.

Have you ever channeled pain to positive results? Ever poured yourself into your profession to avoid your personal life? And if so, is this good or bad?

Escape to obsession

It's 1988 and the early days of Levenger, the company I founded with Lori, my wife. All I do is work. I'm at work before seven and stay until after seven, arriving home just in time to read our two boys a bedtime story. I cherish weekends not for taking a break, but because I can get even more work done without having to commute to the office. On Sunday mornings, I attend the Church of Levenger, the early service, before the family awakes. I'm not avoiding the pain of lost love, but I am running from something else. I had started Levenger relatively late for an entrepreneur, at age 32, after dabbling in several careers without success. If Levenger fails, I have no career to return to. For me, it is Levenger or nothing.

Lori sometimes complains about my incessant work, but fortunately, my mother-in-law never does. She tells me, with her delicate and kind smile, "The world is made by obsessive people, Steve."

Looking back from my vantage point now, almost 30 years later, I see I was running away from the pain and mortification of professional failure. I was running for my life.

Perhaps Alfredo was right and Salvadore was better off not uniting with his Elena. The beautiful man that Jay Gatsby became was fueled by his obsession with his imagined perfection of Daisy Buchanan. Dreaming of her stoked the furnace of Gatsby's blazing vitality and fearsome ambition. When Gatsby finally reunites with his Daisy, she proves to be less than ideal. As readers of Fitzgerald's great American novel well know, Gatsby and Daisy do not live happily ever after.

There is an old expression to wish on your loved ones -- that they obtain everything in life they wish for, save for one thing. And it's left unanswered what that one thing is, just that it be one thing. It's recognition that we humans are at our best when obtaining, not when we have obtained.

Goodbye, San Diego

Have you left a place only to have it remain in your heart forever? Do you have your Giancaldo?

For me the San Diego of 1977 is my Giancaldo. After college, I resolve to leave San Diego to go east to graduate school, but I plan on coming home afterwards. On that last night before I get in my truck and drive east, I take my friend Lynda out to a white-tablecloth dinner in a restaurant on the ocean up in La Jolla. Afterwards we walk along the beach, listening to the crash of the waves. I look out to the moonlit Pacific and say goodbye for now. I take the ocean mist on my cheeks as its kiss goodbye.

As it turned out, I never did return, not to live anyway, and now I have no more family there. When I was a boy, there were dairy farms in Mission Valley. Today San Diego is a megalopolis. Our beloved old Palermo's Pizza in La Mesa, where we went on Friday nights after home games, where Mrs. Motisi brought us hot pizza and yelled at us in feigned anger, is long gone.

***

Farewell, Paradiso

Salvatore follows Alfredo's advice and leaves Giancaldo to live his life in the larger world. When he finally returns, 30 years later, Giancaldo is changed irrevocably. He sees the ruins of his old Cinema Paradiso just before it is scheduled to be demolished. Can he get inside one more time before it's too late?

Salvatore regrets that he doesn't know his mother or sister. Has he made a terrible mistake in this bargain? Was his successful, new life worth the loss of the old?

A promise is a promise.

In the last scene of the movie, Salvatore screens an old film that was an unexpected present, left waiting for him in Giancaldo from his old friend Alfredo. As the film reveals itself, altar-high in Salvatore's screening room, he claps his hands together as if in prayer. What does he see?

I won't spoil it for you, but I will share this. The version of the film you are mostly likely to find online is the shortened, 125-minute version that won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. It is marvelous. Watch that first. And if you thirst for more story, if you want to learn what else happened between Salvatore, Elena and Alfredo, no book will reveal the details because there is no book. Director Giuseppe Tornatore also wrote the original screenplay. But his longer director's cut will fill you in.

What you will find in both the short and long versions of Cinema Paradiso is art upon art that will fill your ears with music, your eyes with tears, and your heart with an old but never quite forgotten love.

And by the way, if you're learning Italian, try turning off the subtitles.