Last November in Miami, I asked Edwidge Danticat if she was working on a new book. Yes, she said, a book of fiction. A novel, or short stories? Well, she said, interlocking stories, and there was some uncertainty or debate over whether it was, or should be presented or read as, a novel or a book of stories. Post-earthquake, I asked, or pre-earthquake? Pre-earthquake, she said.

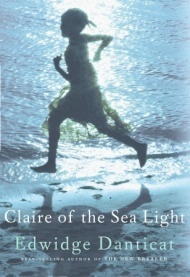

Whether Claire of the Sea Light is a novel or a book of stories is a literary question, one students and scholars are welcome to debate for years to come, now that Danticat has given the book to us. The thing about literary questions is that they often can't, and even shouldn't, be answered definitively. That's what makes them literary. Is As I Lay Dying a novel or a story collection? The allusion is apt, because there's a Faulknerian quality to Claire of the Sea Light, in the way it examines and presents the lives, plural, and life, singular collective, of a specifically imagined local community from multiple points of view, showing how human stories and lives ramify through and across each other in ways both touching and tragic.

I hasten to add that Danticat is a much more accessible writer than Faulkner ever was. But Faulkner's greatness lies in his having built a Nobel-worthy body of work by portraying, story by story, the history and geography of one very specifically imagined postage stamp of a county in an obscure and impoverished corner of one of the most neglected and scorned regions of the American South. As subject matter, Haiti - plus its extensions, ramifications, and implications in Florida, New York, and far beyond - is as rich a vein for Danticat as Mississippi was for Faulkner. Danticat's talent is up to the task, and Claire of the Sea Light shares with us that extraordinary talent in full flower. Perhaps we will be shown the full measure of her achievement some years from now, when the right editor compiles a judicious anthology of her work, fiction and nonfiction, analogous to Malcolm Cowley's Portable Faulkner.

The question of whether Claire is pre-earthquake or post-earthquake is one any reader would ask, but really it's moot. A writer of Danticat's stature and background would and, I think, should be expected to address such a huge and important event. But when and how, and even whether she ever does it explicitly, are matters of her prerogative. Danticat was polite enough to answer my impertinent question, but Claire of the Sea Light is not so much pre-earthquake as sans reference to the January 12, 2010 earthquake that devastated Haiti and dominated the U.S. media for a while before it was inevitably overtaken by other enormities and obsessions. I think there is a point to that. Only Danticat knows whether the point is intentional. Regardless, I think the point in the fact that her first book of fiction published since the earthquake makes no reference to it is that life and death in Haiti are about much more than any one natural disaster or political showdown or upheaval, however frequently or insistently such events might serially loom in the foreground.

I was surprised to learn, from the publicity materials that came with my copy, that Claire of the Sea Light is Danticat's first work of fiction in nine years. During those nine years she has hardly been inactive or ungenerous, giving us a wonderful book of essays, Create Dangerously, and a painfully beautiful family memoir, Brother, I'm Dying, that I consider nothing less than a masterpiece. But Danticat is fundamentally a writer of fiction, and Claire signals a return to her true metier. And this is wonderfully encouraging, because it suggests that, in middle age, Danticat might only now be coming fully into her own as an artist. And that is an astonishing thought, considering how good her earlier work is.

The paradox of fiction as a mode or register of writing is that, although by definition untrue in a factual sense, fiction is good only insofar as it depicts the world truly. This is where the best fiction and the best nonfiction meet. As a journalist colleague once insisted to me, there's no substitute for the sniff on the ground. Or, as Norman Mailer put it, there's no clear dividing line between experience and imagination. The flap copy of Claire of the Sea Light claims that it's written "with piercing lyricism and the economy of a fable." That's true enough, and it fairly represents the strong personal writer's voice and sensibility that Danticat brings to any story she tells. But it doesn't quite do her justice, because she is not only a writer but also, clearly, a listener and a reporter. I don't know Haitian society as well, or any seaside southern-peninsula community as specifically or intimately, as Danticat does, but I do know Haiti well enough to know that Claire of the Sea Light is written not only lyrically but also aptly: it's a product of real experience and observation. The lyricism is a bonus.

Parsing or analyzing the connections among the carefully and subtly drawn stories and characters in Claire is a task for an academic review, or at least for a longer one. This one will have to suffice as an enthusiast's recommendation. That's what I care to write anyway, because the best way to honor such a true and beautiful book is simply to read it with attention and pleasure, then to urge others to do the same. If you have firsthand experience of Haiti, so much the better, but it wasn't necessary to know Mississippi oneself in order to appreciate Faulkner.

One last suggestive thought: The title is interesting because it is one of at least two ways in which the name of the putative central character, Claire Limye Lanme, can be translated into English. The other, unless my command of Haitian Creole is so imperfect as to be incorrect, is "Claire, Light of the Sea." The English phrase sea light can mean lighthouse, and a lighthouse does figure in the book as a significant location and perhaps as a symbol. And one of many startlingly apt authorial observations in Claire of the Sea Light is this one, about a woman from the town's elite class struggling to face the tragedies and losses in her life and community, including some for which she is directly responsible: "Already she was trying to forget her vow to repair the lighthouse. How do you even choose what to mend when so much has already been destroyed? How could she think, she asked herself, that she could revive or save anything?"

Ethan Casey is the author of Bearing the Bruise: A Life Graced by Haiti (2012), praised by Paul Farmer as "A heartfelt account." His new book, Home Free: An American Road Trip, features a conversation with Edwidge Danticat. He is also the author of Alive and Well in Pakistan (2004). Web: www.ethancasey.com. Facebook: www.facebook.com/ethancasey.author