This is the fifth installment in the series, The 3D-Materialization of Art, an ongoing survey tracing the new and growing movement of highly-reflexive 3D spectacle and narrative art and activism. Made by artists who distance themselves from the commercial uses of 3D in motion pictures, television, advertising and gaming, the new 3D artists employ the same technology that the commercial industries use. The difference is the 3D-materialization artists extend the dematerializing values and strategies of Conceptual Art to digital imaging, narratives, mythopoetics, satires and paradigms that promote progressive and sustainable political, cultural and natural lifestyles for the present and future. The other Huffington Post features in the series include commentaries and criticisms on the 3D art of Claudia Hart, Kurt Hentschlaeger, Matthew Weinstein, and the bitforms gallery exhibition, Post Pictures: A New Generation of Pictorial Structuralists A related article includes the digital art of Morehshin Allahyari in a particularly global feminist context.

There is a distinctly authoritarian directive ominously, if sardonically, commandeering us through Jonathan Monaghan's 3D film loop, The Pavilion. Of course the best artists always compel us to see worlds we aren't ready or don't want to see. But the imagery that Monaghan mashes together from the pixels of real photographed consumer products and high-end real estate is composed to purposely impose upon our minds the signage of imperious expectations and rarified tastes that we instantly read to be issued from "above". That we so easily recognize Monaghan's The Pavilion to be the abode of the oligarchical class despite their physical absence indicates the degree to which we have had to contend with oligarchy in our lives and have even grown accustomed to its ubiquitous presence.

We of course read the luxurious interiors and perverse technological innovations and artifacts to be the playthings of the rich and powerful. It helps that Monaghan's 3D mise-en-scenes are so real in appearance as to represent the most tangible of elite tastes, firstly, in a haute-couture showroom of militaristic riot gear for the oligarch with stringent security and defense needs at home and at work, and secondly in a luxurious bed chamber and its encompassing closet designed for ... him? her? The oligarch's gender is not only withheld, it is irrelevant to our cultural present. All that matters is that the oligarchical class is represented through the signage of their possessions and lifestyles as a permanent if ominous American fixation of usurped power and the obscene imbalance of wealth acquired through the flattening of democracy.

Monaghan's cutting-edge visual and conceptual designs convey that he is as capacious in his vision, as meticulous in his craftsmanship, and as mythopoetically literate as either Mariko Mori or Matthew Barney. Monaghan leaves his mark on 3D with the evocative stillness he imposes on a medium commercially designed for generating the fast and furious mainstream animations of blockbuster cinema productions that reduce audience attention spans. Presenting a stark contrast to the knock offs of popular culture, Monaghan distinguishes himself from the 3D artists informed by popular animation, as well as from those who use 3D to extend the media of painting and sculpture . In The Pavilion, Monahan's slow conveyance of the viewer's gaze through expansive 3D spaces filled with streamlined objects and real brands reveals his visual literacy has been conditioned by advertising and cinema, two fields that share a decidedly intentional (as opposed to incidental or aesthetic) aim to their designs. In this regard the intention in The Pavilion manifests as a heightening of the ambience of largesse and cultural virility.

With objects mimicking all the artifice of advertising -- the magic of immanent wish fulfillment; the fetishistic stimulation of eroticism; the invocation of power and status -- Monaghan's visualizations simulate the virtuoso technics of cinema: the motion capture of camera zooms, pans and ellipses; the compositional panoramas of the full depth of field; the montage of scenic juxtapositions. Monaghan further adds to the illusion of The Pavilion's realism by making his survey of rooms appear direct, candid and emphatic, even as he employs the ruses of advertising and the seductive tropes of cinema to construct a semiotic and existential comic-tableau satirizing the media's direct intersection with the imperatives of the oligarchical class.

When we are conveyed first into and through the antiseptic showroom of The Pavilion, we take in the semiotics of a defensive power so real in its display of paramilitary riot gear, some of us may be baffled about whether to laugh or to shudder at the signage of the American militaristic imperative on display with all the design imperative and gentrified discretion of an Armani emporium or a Prada boutique. Exiting the showroom, Monaghan escorts us to an elaborately minimalist bed chamber outfitted with a status-affirming consumerism so pronounced it could easily be mistaken for a temple to compulsive consumption, a modern pharaoh's tomb outfitted with an array of closets concealing all the artifacts required of the afterlife. Naturally an iconography of class, especially that concerning a class which enshrouds itself in remoteness and privacy, is always predisposed to cliche and stereotype -- the invasion of the ideal at every step of interpretation. But Monaghan's sense of humor brings both cliche and stereotype as much into focus as subjects of his satirical pictorialism as he does the rich we largely imagine. In short, The Pavilion is more about our envy and fantasies of the rich and powerful than it is about them, and in this Monaghan draws a caricature that is no more a portrait than are conventional Hollywood movies.

If his mashups of the showroom and bed chamber convey Monaghan's understanding of the sociology of design in marketing, it is Monaghan's cinematographically-styled, yet entirely-simulated long shots, slow zooms and pans that steer our visual conveyance into and through the showroom, then out its doors to the open expanse of horizontality defining the immaculate bedchamber. Monaghan's videos comprised of simulated slow camera pans and zooms of imagined landscapes, interiors and objects are informed more by such signature sci-fi films as Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, Andre Tarkovsky's Solaris and Ridley Scott's Alien and Prometheus, only transferred to earthly and decidedly corporate and global terrain. It's more than just the software simulating a real camera filming an elaborately futuristic soundstage set that commands our attention. It's the simulation of a camera simulating the human gaze that Monaghan evokes with the mastery of a cinematographer. And it's the mood that the music and audio discretely imparts.

It is exactly this formal yet imaginary play on a camera's capture of still and luxurious spaces that recalls the faux Louis XVI bedchamber at the end of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Even more importantly, Monaghan recreates for audiences in 2015 the kind of disorienting experience that Kubrick introduced to unprepared audiences in 1969. The difference, of course, is that Kubrick photographed his speed-of-light parable on a soundstage furnished with props, whereas Monaghan, sans camera and film crew, has done no more than computationally cropped disparate photographic details of high-end furnishings and decorative objects that he then recomposes into ultra-glossy animation stills. It is such stills that Monaghan slowly enlarges onscreen to effect the illusion of a physical camera's approach through space. In short, Monaghan is making that film which the Motion Picture Industry has predicted since the invention of motion capture technology will be made without live actors and physical sets.

As far as 3D goes, Monaghan's simulation is simple, yet it is the simplicity of the illusion that makes the effect all the more challenging to our preconceptions of reality and ideality. If we have learned anything from the history of art, it is that it takes very little formal alteration to a picture or an object to transform it from a model of reality into a representation of ideality, and vice versa. It is this simplest of visual magics which make all the debates over what is real and what is ideal -- as argued by philosophers since the Greek PreSocratics and the Indus Vedic scribes, and over the centuries reconfigured the debates of epistemologists and phenomenologists, existentialists and ontologists, structuralists and culturalists -- all over what is the distinction between and the linkage mediating the real and the ideal, when they in fact may very well be the same.

The real vs. ideal debate is neutralized more by 3D than any other medium, including photography, though it is with his mashups of photographs that Monaghan's renderings reconcile the debate of the real vs. the ideal at least artistically. But so far I have only accounted for Monaghan's simulation of the real, which is in fact it's opposite, the ideal. To account for the real real, we must also look to its opposite in the ideal, or what in The Pavilion appears as the surreal. For it is in the working out of the creative process of the mind as a surreality (or ideality) that we in fact manifest the reality that is always a construct of consciousness.

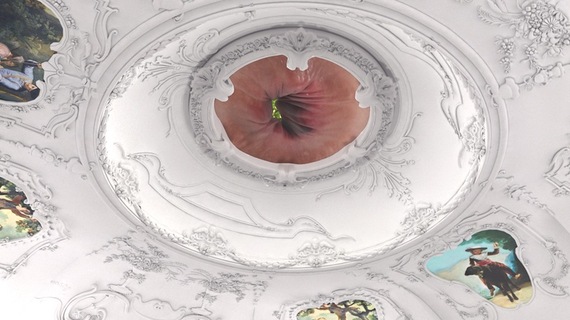

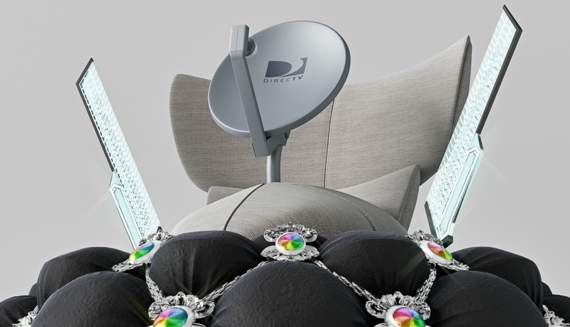

The transformation from the appearance of the real to the realization of the ideal is so slow that it takes a moment for the viewer to register that at the center of the bed chamber ceiling is the musculature of a tightly-closed sphincter. The real has suddenly become the surreal as the sphincter opens to reveal the sky. Then, as the orifice widens, through it descends a biomechatronic egg designed after that supremely imperial object'dart, the Fabergé Egg, only now upholstered in black-leather and outfitted with a pair of human testicles on its anterior (because the oligarch no doubt believes it takes balls to be a raider and pillager of the little people's savings and property.) It is one of Monaghan's series of eggs referencing the architecture, corporations, genetic and biomechatronic experiments of the past and present, all crafted with the interests of today's global oligarchy in mind.

At this point, the video engaged with the surrounding gallery exhibition comprised of an edition of computational collage prints rendering variations on Fabergé Eggs, each similarly technologically, decoratively and architecturally enhanced. Monaghan's Eggs have all the right consumer touches to make the work both compelling as uncanny design and social satire, though he may have gotten a bit too derivative of Matthew Barney in his recourse to the biomechatronic motif better known as the cyborg. But as one of the truly contemporary creations of the last century, the cyborg is likely to long be a mine of the uncanny, with the choice of what human anatomy is grafted onto what object and technology yields the desired results. Making his cyborgs not living beings but human-fabricated techno-consumer objects with miniature architectural structures, even a Starbucks store, is Monaghan's genius stroke. The cyborg that appears at the center of the bed chamber's ceiling as a sphincter opening as a skylight is the surreal ideality that propels us through to the end of the video, the whole point seemingly postulating that all reality must finally submit to an ideality of mind, whether human or godly. Even if it is no more than the product of a god's anal emission, it is a fitting end to the paleolithic origin of the artist as emulation of the god creating a world the the world's creation myths convey.

What causes these virtual objects to hold a strange and ominous power over the gaping viewer is their glimmering realism, the kind we see reproduced in high-gloss magazines. Monaghan's still photo-collages are our era's version of the 17th-century Dutch and Flemish vanitas and pronk still-lifes, replete with their moralizing ironies reflecting the transience and superficiality of such worldly and sumptuous veneers as vain and intemperate illusions. We can see in them, as consumerist microcosms, the hyperbolic expectations that begin by sheltering us from the ravages of time and space but which ultimately must yield to them. But rather than getting stringent about consumerism, Monaghan is a true late capitalist in poking fun at the moralism of anti-capitalist ideology.

With the Freudian fetish arguably devalued in a Western society that no longer has its erotic desires restrained by severe moral codes, the current generation of artists conflate the body with the inanimate object not as some clandestine repository of sexual desire (say in finding arousal in the folds of a hat that double for the vulva), but as a formalist-inspired empathy with objects for their aesthetic appearance, functionalist extension of the body, and social denotations of status and wealth. This denotation can be either or both consumerist and aesthetic. Of course the cyborg was born with science fiction -- chiefly such visually futuristic media as comic books and cinema that the new conflation became identified as the cyborg. By the 1980s the cyborg became a paradigm of radical transformation of identity politics with the feminist film theory of Donna Haraway's elaboration of the cyborg as a motif of empowerment for women, a signage and narrative structure that confers a superhuman ability available to women for transcending the imposed cultural and social limitations absent in the realistic mainstream media representations.

But the cyborg principle at work in Monghan's videos and photo animations emphatically reinforce the theory that art making is ultimately an expression of our unconscious desire to rejoin with the material world, the forces that have created it, or, more pragmatically, to join the real with the ideal. For the material to most of us is what is shared and thereby composes and defines the real. Conversely, the ideal is what we only resentfully admit to being private however much we will it to be the way of the world. It is a duality that perhaps motivates the artist more deeply than aesthetics or ideology. It is because the ideal cannot be made real in any collective sense that it is channeled into art, that nexus which culture vents publicly as if to placate the urge to make the ideal real in some larger revolutionary sense.

Returning to The Pavilion's affinity with Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, we can consider Monaghan's descending cyborg egg in the oligarch's bed chamber to be the uncanny equivalent of the appearance of the space pod in Kubrick's bed chamber at the end of time (what Einstein held to be arrival at the speed of light). Except that, in its day the bed chamber scene shattered the filmgoer's faith in the illusion of realism and the linear narration of cinema. Of course art audiences today are better equipped to receive the comic surreality of Monaghan's descending giant cyborg egg as the reality of simulation announcing itself. But we still consciously receive the simulation of the descending cyborg egg as if it were an elaborate prop descending in real space before a movie camera situated on a soundstage, when we are really only seeing an algorithmic calibration for scanning and enlarging a photo-computated collage as an animated illusion. Of course how much and if the audience is fooled by such a simulated subterfuge depends on its literacy in 3D platforms and tools. The 3D-informed audience however receives the reality of the simulation.

The point is that it is only after Monaghan steps up the surrealistic stylization of his video that he abandons the physics and visualizations of realism and introduces the idealities and surrealities that are the real reality at hand.

All in all, The Pavilion is Monaghan's discreet declaration that at the center of all reality is our projective ideality, and that it is this ideality that 3D excels at rendering as a reality unlike any medium before it. In his convincing 3D-materializations, Monaghan's art counts among our generation's most photorealistic illusional models of 3D art in that it passes for both a photographic and cinematographic record of real objects, spaces and gradations of light. While the revelation of the ideality simulated as reality is entertaining in the first few viewings, a more complex dialectic comes into play once the fuller phenomenological implications -- that is once an awareness of the structural features of consciousness at play throughout The Pavilion -- make themselves known. And with this phenomenological scrutiny come various proposals of a linkage, or a continuum, or a competition, between the reality of the world with the ideality of the mind busily at work mediating that reality.

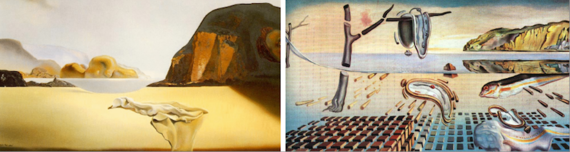

In the second video loop of the exhibition, the twenty-minute Escape Pod, 2015, Monaghan returns to his former animated reveries -- what can be called the mythopoetic ideality -- that is the making of new myths for our times out of the motifs and narrations of old, even ancient mythologies. Unlike The Pavilion, Escape Pod is informed almost entirely by the legacy of traditional animation and surrealist painting even as it brings a certain luster and contemplation that is foreign to most animation. It is also informed by ancient mythologies of the hunt, specifically those of Norse and Greek variety centering on the plight of the Stag and its symbolic references to the life stages of birth, maturity and death. To add to the complexity, Monaghan transposes the Stag to modernist spaces largely rendered with conventional animation software, though here too there is a photographic departure especially noticeable in the forest and water settings.

Yet for all its mythopoetic ingenuity, Escape Pod is altogether more traditional in its narrational structure and visualization and less reflexive in its imagery's relationship of the structures of our experience of the world, consciousness of mind, and the modeling of reality and ideality simultaneously in terms of pictorial narration. A mountain landscapes evocative of Salvador Dali conveys that the imagery of dream is being conflated without the iconography of traditional myth in the engaging and beautiful figure of the golden Stag. While the mountain motifs and other landscape imagery recall the sensory-motor coordination of traditional painting, the animals that embody Innocence in Escape Pod come into being with the animation modeling designed for cartoons, however much they are rendered here with heightened technical finesse, greater dimensionality and a more dreamlike arbitrariness and futility of purpose. But what distances Monaghan's cartoons most from the renderings of commercial productions is their sense of bewilderment and loss of meaningful direction in their imperative of escaping -- What? -- an unseen yet ominous fate that traditionally was the hunter, sometimes a god, but here seems to be an existential if unseen entity representing ubiquitous, dangerous and deadly pursuit, capture and containment.

Escape Pod is at its best a conflation of archetypes and analogies concerning innocence and its loss amid a commercial and autocratic superstructure. But its mytholopoetic treatment makes the appearance of the animal cyborgs less incongruent, since there is no rendering of reality to be incongruent to. Instead of a theoretical contemplation to ponder, we relax in an sardonic entertainment, sometimes filled with the pathos of the innocent, yet breaking into a comic surreality with the descent of a hovering giant architectural spacecraft, again equipped with anterior testicles, and foretelling the oligarchical race of the future.

To his credit, Monaghan is an impeccable formalist and compelling steward of the audience through a uniquely tangible succession of spaces, each real and captivating enough to impel debate as to how much the artist's control over what we see is autocratic to the point of reducing the viewer to a passive observer, as opposed to an active participant. But this is his point. Whether or not he has in mind Guy de Bord's theory of the consumer society spellbound into political inaction and subservience by the spectacles of capitalism (see my Matthew Weinstein feature), Monaghan is circumnavigating us through an array of the late capitalist, corporately-branded spectacles keeping us riveted to them at the same time that we discern their allure is a mirage of mythological thinking distracting us from real action.

Earlier videos by Monaghan which pay a more direct homage to the cartoon legacy of animation make our political distraction by entertainment abundantly clear. But the superrealism of the new work confuses such cautionary prompts in being so very seductive in their technical proficiency. I personally prefer this ambiguity, as it is the one lapse in the Monaghan vision that allows us some resistance to the artist's commanding moral and political steerage of our experience of his art. For even when we agree with an artist's point of view, the impulse for individuality compels us to search out some flaw or lapse that facilitates our departure.

Perhaps the greatest human flaw is our proclivity to be seduced by the delusion of reality. It imagines that we can know the world without any interference from our own personal and social experience. As if we can see without the structure of our own eyes and brains mediating, interfering. Reality is the delusion that we can see the world as it is, rather than the world as we make it appear. It is why I don't use the term virtual reality to refer to or describe 3D animations. For all reality is virtual, while 3D as a category makes obvious what the human mind dimensionally shares with the reality that is so elusive to the mind.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on facebook.