How often have you heard that old saw about Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil at midnight on a Delta crossroads? It all started because of Johnson's uncanny mastery of the guitar. A small-boned man with long, slightly webbed fingers, Johnson earned respect and kept fights at bay with his astonishing musicianship. Johnson may have had eidetic memory for music -- the ability to hear and then recall music with unusual precision.

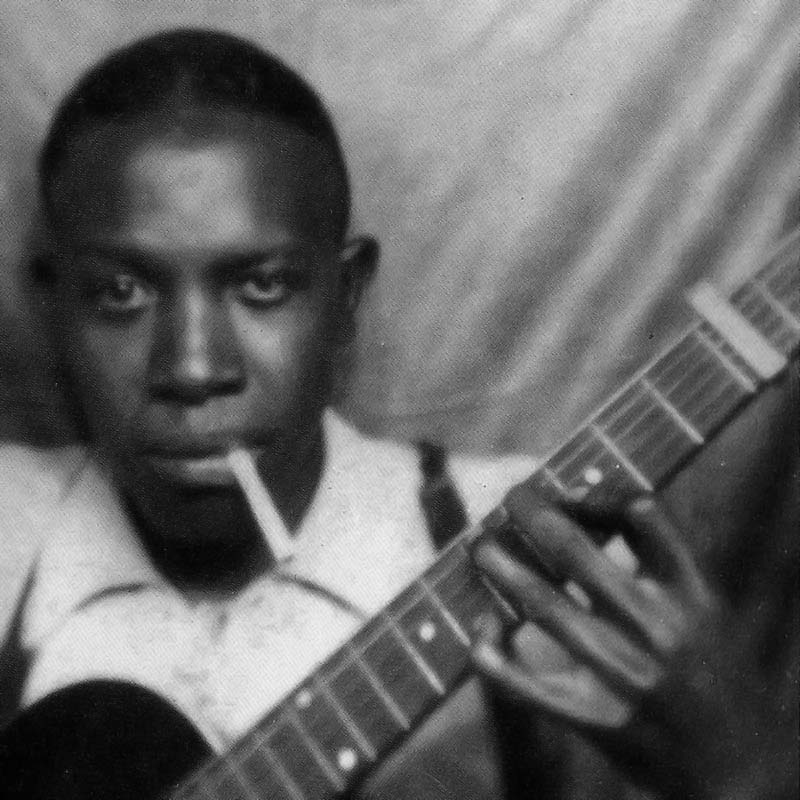

(Robert Johnson took this self-portrait in a photo booth in the early 1930s. © 1986 Delta Haze Corporation, all rights reserved; used by permission)

(Robert Johnson took this self-portrait in a photo booth in the early 1930s. © 1986 Delta Haze Corporation, all rights reserved; used by permission)

As Steve LaVere wrote in the Robert Johnson: The Complete-Recordings liner notes: "He could hear a piece just once over the radio or phonograph or from someone in person and be able to play it. He could be deep in conversation with a group of people and hear something -- never stop talking -- and later be able to play and sing it perfectly. It amazed some very fine musicians, and they never understood how he did it." Guitarists are still trying to accurately suss out Johnson's sophisticated chord voicings and unusual tunings.

Johnson also loved to read, according to my interview with his common-law stepson, Robert Jr. Lockwood, for The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu

"Johnson lived with my mother [Estella Coleman] common law for about eight, nine years," said Lockwood, who was born in 1915 in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas, making him 90 when we talked in 2005. "He taught me to play. Can't nobody play his stuff but me." The family lived in Helena, Arkansas, and also spent time in Memphis and St. Louis, while Johnson performed throughout the Delta.

Because of their close relationship, Robert Lockwood was nicknamed Robert Jr. He performed as Robert Jr. Lockwood his entire life, winning a posthumous Grammy in 2008 for Last of the Great Mississippi Delta Bluesmen... Live in Dallas, recorded at Eric Clapton's Crossroads Festival with Henry James Townsend, Pinetop Perkins and David "Honeyboy" Edwards.

Lockwood was sharp as a whip when we spoke, and brooked no nonsense. "What did I think about Robert Johnson?" Lockwood said, "I think he's a nice man. All them stories about him, I don't know about that. He never told me nothing about it."

Lockwood described Johnson as highly intelligent, curious and constantly seeking inspiration for songs like "Cross Road Blues" and "Stones in My Passway," which describe hoodoo practices in detail. When I asked Lockwood where Johnson got this information, he replied, "I have to say that he done quite a bit of studying in his life. He did a lot of reading and stuff like that. Just about anything you could read, he read it. You read things and after you get through reading about it, you can sing about it."

Hoodoo is not Voodoo, though the two are often confused. Voodoo (properly spelled Vodou) is a New World religion derived from West African Vodun. (For more info, please see my post Possessed: Voodoo's Origins and Influence from the Blues to Britney.) Hoodoo is a folklore system of stories, herbal medicines, and magic practices drawn from African, Native American, and European sources. Many hoodoo practitioners can recite chapter-and-verse from European occult books like The Black Pullet, Secrets of the Psalms, and The Book of Secrets of Albertus Magnus.

Examples of hoodoo include mojos, foot track magic (like placing stones in someone's passway) and divination spells to tell the future. But just because blues musicians used hoodoo imagery in their songs to wonderful effect, that doesn't mean they believed in it. As Lockwood remarked, "I don't believe in it. I don't believe nobody can do nothing without my wanting them to do it."

Pianist Henry Gray, who played in Howlin' Wolf's band from 1956 to 1968, expressed similar feelings to me. Gray, who grew up near Baton Rouge, recalled how people who feared they'd been hoodooed would "go across the river to a place in New Orleans called The Seven Sisters; they supposed to be able to read your palms, tell your future. I never believed in that stuff but a lot of people do, and they would go get a [mojo] hand removed or whatever they needed done."

Gray also played with Muddy Waters in Chicago and described how transplanted Southerners like Waters and Ernest "Tabby" Thomas would work hoodoo imagery into their songs: "Well, hoodoo, that would come up in songs like 'Hoodoo Party' by Tabby Thomas, and Muddy used it in "Got My Mojo Working." He was using it for a song, you know, but he really didn't believe in it."

Johnson never claimed to have made a pact with the devil; that boast was actually made by Tommy Johnson, known for his own intricate guitar playing on songs like "Canned Heat Blues." According to LaVere, "the crossroads story was also told by [guitarist] Ike Zinermon, Robert's primary mentor, and for Robert Johnson by Son House during interviews in the mid-1960s."

Johnson recorded "Cross Road Blues" in San Antonio, Texas, on November 27, 1936, and both his musical genius and intellectual sophistication are on display in this song.

In the first verse, Johnson goes to the crossroads and falls to his knees, crying out to God to save him. In the second verse, he stands and tries to flag a ride as dusk descends.

In the blues, "rider" is slang for a lover and also a metaphor for divine possession. In Vodou ceremonies, ancestral spirIt-gods called loa descend to "ride" members of the congregation who have reached a state of readiness for ecstatic union with the divine. The morality implicit in this is stated in the Haitian proverb, "Great gods cannot ride little horses." The loa also like to hang out at a crossroads, waiting for a worthy soul to ride.

The concept of a deity "riding" a worshiper transferred to Pentecostal churches, where the cry "Drop down chariot and let me ride!" was often heard, as well as "Ride on!" and "Ride on, King Jesus!", from congregants seeking to be filled with the Holy Ghost. What's striking about "Cross Road Blues" is Johnson's expressed sense of failure at having dug into his spiritual resources and come up empty-handed. Rather than providing a pat story of being lured by the devil or saved by God, Johnson stands at the crossroads, sinking down, crushed by existential dread. Christianity has failed him, and the ancestral rites that might have restored his connection to his own divine nature are lost to him:

Standing at the cross roadsI tried to flag a ride Didn't nobody seem to know meEverybody pass me by

Nonetheless, rumors of Johnson's crossroads pact persisted, fueled by his supernatural musical abilities. Johnson's death in 1938 at age 27 put the seal on the legend of his deal with the devil.

Johnson, harmonica player "Sonny Boy" Williamson, and Honeyboy Edwards were entertaining at the Three Forks juke in Greenwood, Mississippi, when Johnson suddenly fell ill. Johnson had been playing at the joint for a few weeks, and was having an affair with the owner's girlfriend.

Johnson and Williamson were standing outside on break when someone handed Johnson an open half-pint of corn whisky. Williamson purportedly knocked it out of his hand, saying "Man, don't never take a drink from an open bottle. You don't know what could be in it."

Irritated, Johnson snapped, "Don't never knock a bottle of whiskey out of my hand." When a second open bottle was proffered, he took a swig. Johnson and Williamson returned to the stage, but several minutes into their set, Johnson could no longer sing. Williamson covered for him on vocals but after a few more tunes, Johnson put down his guitar.

By the time Edwards arrived around 10:30 p.m., Johnson was retching and delirious. He was laid across a bed in an anteroom and taken early the next morning to his room in "Baptist Town," an African American neighborhood in Greenwood. Although he was removed from Baptist Town to a house on the "Star of the West" plantation, where he was nursed around the clock, Johnson died August 16, 1938.

To the people who loved him, his death was the hard loss of a sensitive, talented person. "I was pretty shaken up," Lockwood told David Witter of Chicago Interview. "I didn't play for over a year. As far as my mother and I were concerned, he was a wonderful, wonderful man."

Johnson's songs have been monster hits for rock musicians, who continue to mine his 29-song repertoire. Led Zeppelin ("Traveling Riverside Blues"), The Rolling Stones ("Love in Vain"), Cream ("Crossroads"), the White Stripes ("Stop Breaking Down") and more have turned Johnson's songs into rock, funk and heavy metal gold, which is why he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1986.

These artists all heard the blueprint in his songs for the future of popular music. "Robert was way ahead of his time," mused Lockwood. "He sounded different. When Robert played the guitar, he played the whole guitar. He played the lead and the background and everything. In the end, rock and roll ain't nothing but the blues played fast."