How does a three-year-old book on the hidden history on one of the most famous museums in the world get reborn with a new following?

New dirt, more scandals. They pour out of a book that profiles the curators, city planners and barons of American high society, anyone with oversized egos, through a dual thread that captures the history of New York City and the United States.

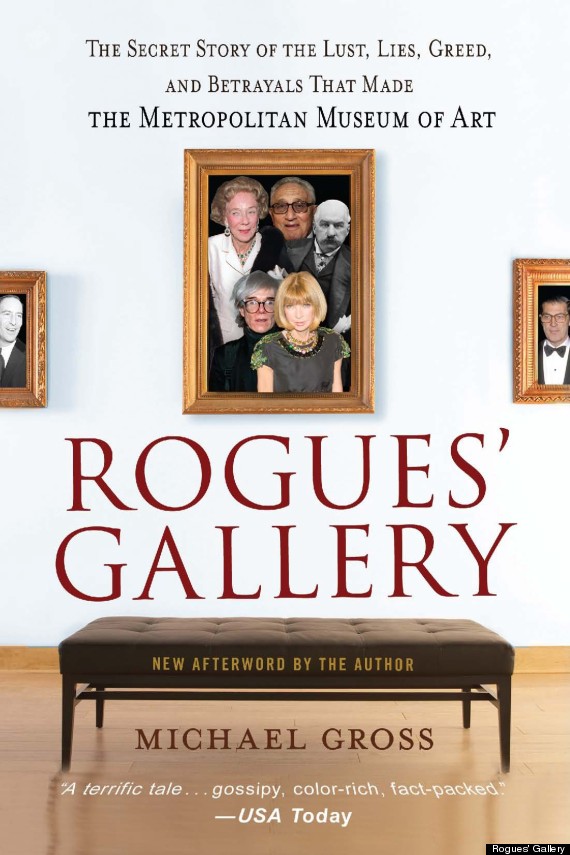

With names like Morgan, Rockefeller, Lehman, Kennedy, Kissinger, Eisenhower, Sulzberger, Kravis, Koch, IBM, Moses, Lindsay and countless others, not to mention all of the great artists whose art adorn the halls of the Met, Rogues' Gallery: The Secret Story of the Lust, Lies, Greed, and Betrayals that made the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a tour de force read on many levels.

First, the history of the Met and its odd relationship with New York City are chronicled. It begins with its initial plans to green light the construction of the museum along five city blocks on Fifth Avenue. For the next 75 years, the Met kept its murky books, running some years in the red, out of view of the public eye. Today its annual report is displayed online.

The Met's disdain for the public and the city -- with equal contempt and moxie, except for taking their money -- dates back to the museum's grand opening in 1878.

Today, two lawsuits have been filed, in a NY Post article, on whether the Met can force its entry-fee on the public. So the tussle between the Met and the public, not settled after 135 years, will carry into the foreseeable future.

The dance between the Met and city hall included public battles over budgets and the many expansion plans with NYC Parks commissioners, from Robert Moses to Henry Stern. In the first years of operations, the Met fought the common folk, resisting cries to open the museum on Sundays so the working citizen could visit.

In the 1950s, the Met tried to pass on wage increases of security guards making $60 a week to the city, which said 'no.' The Met retaliated threatening to no longer care for the plants outside its building, passing that expense onto the city. When that didn't work, the Met closed the museum on Mondays, which is still in effect today.

This summer the same strip of Fifth Avenue is under a massive renovation project, which for the Met seems to happen every decade.

By 1970, with construction with no end in sight, spurred the city to make the Met come up with a "master plan." Reluctantly, the Met complied under then Director Thomas Hoving.

The Met as Fiefdom

In the book: "'Hoving's museum would be virtually complete, its three mismatched sides wrapped in limestone and glass.' The master plan 'seems to make real sense at last,' the art critic Paul Goldberger wrote."

As divided and patchwork as the master plan, internal territorial battles fought over the budgets, exhibits and what art to buy. Those struggles of personalities played out between museum directors and curators-as-showman in Francis Henry Taylor and Thomas Hoving. Those men filled both positions over their storied careers, giving Rogues' Gallery the juice to make the 500-page tome an enjoyable read.

Taylor and Hoving wanted to open the museum more to the people. They were rebuffed.

In the book's introduction:

The Metropolitan occupies state-owned building sitting on public land; has its heat and light bills, about half the costs of maintenance and security, and many capital expenditures paid for by New York City; receives direct grants of taxpayer dollars from local, state and national governments; and for most of its existence has indirectly benefited from laws that allow, and even incentivize, private financial support in exchange for generous tax deductions. So it is clearly a public institution.

But "It has functioned as a private society," Gross writes.

With such dead-on observations and others about board fights turns a historical book into a page-turner. Add the period of 1890-1910, when the American industrialists raided the artwork of Europe and the book shows the Met as a global institution in the making. The periods of growth and change are punctuated with stories, such as the "Three Museum Agreement" between the Met, Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney. It was a "sweetheart deal for the Met, which stood to gain thirty years of modern art with little expense or effort." Nelson Rockefeller negotiated the deal. "The Whitney, however, really took it on the chin. It got to disappear into the Met."

In the book's introduction, Michael Gross notes that the "arrogance" has toned down. But he also lays plain that the museum, which looks at how to turn space into dollars -- the reason behind the myriad expansions, conversions and retrofits -- often seems to be more focused on commerce than art.

He wrote: "The Met's Web site refers to only seventeen van Gogh paintings and three drawings. The central catalog, a card file of museum holdings that was once open to the public, 'is no longer updated,' a member of that department emails in response to a request for information, so 'is now rather incomplete.'"

Van Gogh and request for information centers a second controversy that has bubbled up this summer on whether there is a copy of a van Gogh that has both been on display since it was gifted from the Annenberg Foundation in 1993.

If the van Gogh -- Wheat Fields with Cypresses -- proves to be a copy, it would come in as the fourth, and biggest, controversy to hit the Met since its inception, from J.P. Morgan purchase of suspected forged artwork to a slander lawsuit on a "Gothic statue Demotte had sold Joseph Duveen (which he'd left to the Metropolitan), and declared it a fake."

Reaching out to the Author

In contacting Michael Gross by email, it appears nothing regarding new scandals at the Met would shock him. Why would it? From the start, the Met tried to dissuade him from writing the "unauthorized" book on the history of the museum.

"What inspired you to write it?" I asked.

"I wanted to use an institution to tell the story of how the city's upper class uses cultural philanthropy to enhance its social stature," he replied.

"Did any period of history or person surprise you?"

"The story of Jane Engelhard is my favorite in the book and was a total surprise. I think of it as Casablanca if Edith Wharton had written it," he said.

Thomas Hoving hired Jane Engelhard in 1974, "the wife of a precious-metals magnate" to the board of trustees. In the last chapter, "Arrivistes: Jane and Annette Englehard 1974-2009," Gross captures her influence and network within the fashion community, which reflected the changing times, mores and economic growth of the city in the 1980s.

Hoving inspired to the end of his reign, when in "March 1976, he celebrated his ninth anniversary as museum director by writing a letter to (Walter) Annenberg, outlining a strategy to create an Annenberg center within the museum, dedicated to the visual arts."

Hoving was also instrumental in bringing the famous King Tut exhibit to the Met in 1978.

If there's one minor complaint about Rogues' Gallery, not enough was written about the Annenberg Foundation's March 1991 announcement: It picked the Met to receive its $1 billion gift of artwork, including several van Goghs, among other masters of his era.

Like Hoving, Michael Gross brings life to an unseen dimension of New York City in the show and lore of high society, scandals included.