Update: After a flurry of comments and emails regarding this post, ranging from appreciation of my essay, to articulate disagreement, to insane sexist supposedly anti-rape salvos, I've written my take on the Polanski case, at my site. I wrote this piece not to defend his original actions, I wrote this piece to explicate his art. Read here.

I'm not going to go into my Roman Polanski defense. I've been doing this all morning, nearly ranting and raving over my views on the matter, and have grown frustrated and depressed. But in short, I'm not happy about his arrest. So, I would rather discuss one of his greatest pictures, a brilliant portrait of female sadness, alienation, sexual neurosis turned to psychosis. A movie all women should watch -- his masterpiece "Repulsion."

"I hate doing this to a beautiful woman."

--Roman Polanski cameraman Gil Taylor

Roman Polanski knows women because he understands men. He knows both sexes because he understands the games both genders play, either consciously or instinctively. He understands the perversions formed from such relations and translates them into visions that are erotic, disturbing, humorous and, most important, allegorical in their potency. One should not (as so many did with his misunderstood Bitter Moon) take Polanski's films literally, for they are often heightened versions of what occurs naturally in our world: desire, perversion, repulsion.

Film writer Molly Haskell said that at the core of Polanski's work is the "image of the anesthetized woman, the beautiful, inarticulate, and possibly even murderous somnambulate." Her observation is astute, but it's followed by the tired criticism that in all of Polanski's films, including Repulsion, "the titillations of torture are stronger than the bonds of empathy." Of course. Polanski's removed morality is exactly why he is often brilliant: He is so empathetic to his characters that, like a trauma victim floating above the pain, he is personally impersonal. He insightfully scrutinizes what is so frightening about being human, yet he doesn't feel the need to be resolute or sentimental about his cognizance. He is also, consciously or subconsciously, aware of the darkness he explores, especially in his female characters, who could be seen as extensions of himself. 1965's Repulsion proves as much.

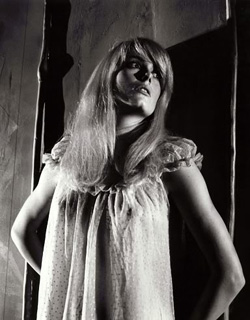

Starring ice goddess Catherine Deneuve, Repulsion is one of the most frightening studies of madness ever filmed. Deneuve plays Carol, a nervous young manicurist who shares an apartment with her sexually active sister (Yvonne Furneaux). At first Carol goes about her days in the salon, where she quietly tends to bossy old ladies' fleshy cuticles; walking outside, where she unsuccessfully avoids the leering glances and advances of men; and languishing about the apartment, where, with disgust, she listens to the noises of her sister's lovemaking and silently despises the men who visit. She exhibits a pathological shyness and repression that slowly spiral into madness after her sister leaves on holiday. Carol's dementia creates perplexing hallucinations: sexual acts with a greasy man whom she simultaneously loathes and lusts after; greedy hands poking through walls and kneading her soft flesh; and the moving and cracking of walls. Left alone, she is able to act out what she is so afraid of: the dark sludge of desire.

The obscure, slippery and decayed complexities of such desire are conveyed brilliantly in Repulsion. The diseased atmosphere of Carol's womb is meticulously created with Polanski's use of camera angles, sound effects and images of clutter. Though music is used effectively, Polanski relies more on amplifying the sounds of everyday life -- the ticking of a clock, the voices of nuns playing catch in the convent garden, the dripping of a faucet -- to convey the acute awareness Carol acquires in response to her fear. Polanski also dresses the film with pertinent details that further exemplify both Carol's madness and the aching passage of time: Potatoes sprout in the kitchen, meat (rabbit meat, no less) rots on a plate and eventually collects flies, various debris of blood, food and liquids form naturally around Carol. The film's inventive use of black-and-white film, wide-angle lenses and close-ups creates an unsparing vision of sickness, and Deneuve's performance is effectively mysterious. The viewer, however, is able to empathize with Carol, which is how she lures us into her web in the first place. As Polanski cameraman Gil Taylor muttered during filming, "I hate doing this to a beautiful woman."

And yet, one loves doing this to a beautiful woman, especially one like Deneuve. Deneuve's loveliness makes Carol's madness more palatable (her unfortunate suitor thinks she is odd, but he can't help but "love" this gorgeous woman), but eventually it becomes horrifying. Carol is not simply a Hitchcockian aberration of what lies beneath the "perfect woman," she is the reflection of what lies beneath repressed desire -- in men and women. Polanski has a knack for casting women who are nervously exciting (Faye Dunaway in Chinatown is a blinking, twitching mess), and therefore dangerous to desire. He makes one insecure about longing for them.

And Deneuve is certainly nerve-racking. She is so physically flawless that she often seems half human: An anemic girl, she can barely lift up her arm, yet at the same time she is highly sensual, an ample, heavily breathing woman with more than a glint of carnality in her dreamily vacant eyes. Deneuve makes one feel the confusion of a corrupted child: She is an arrested adolescent who, like an anorexic, cannot face her womanliness without visions of perverse opulence and violence. Carol is the personification of sexual mystery -- she is what lurks beneath the orgasms of pleasure and pain. What Polanski finds intriguing and revolting is perceptively female, making Repulsion a woman's picture more than women may want to know, or care to face.

Read more Kim Morgan at Sunset Gun.