On the 500th anniversary of his death, medieval Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch is a smash hit. To meet the demand for "Jheronimus Bosch -- Visions of genius," the Noordbrabants Museum in Den Bosch has added 30,000 tickets to the 350,000 tickets that flew out the door. Between March 24 and May 8, the museum will stay open until 11 pm, seven days a week.

Crowds are flocking to Bosch's hometown for his largest retrospective to date -- a remarkable reunion of most of his known works. Some 17 paintings (panels and triptychs) and 19 drawings are organized into six thematic sections. Five hundred plus years after their creation, Bosch's highly original monsters, demons, angels and saints are resonating with viewers.

Over the centuries, natural aging of the material components of the paintings and human intervention have adversely affected some of Bosch's works. Nine were able to travel to the Netherlands thanks to conservation treatment spearheaded by the Bosch Research and Conservation Project, a team of experts in different fields formed in 2010 to analyze the artist's oeuvre.

Among Bosch's works to undergo conservation were three polyptychs from Venice, Italy. Two triptychs from Gallerie dell 'Accademia -- St. Uncumber (1505) and The Hermit Saints (1510) -- were in desperate need of restoration. In St. Uncumber, the central panel represents the crucifixion of a female saint, Uncumber, flanked by St. Anthony and a monk leading a soldier. Bosch anchored The Hermit Saints with his namesake St. Jerome, along with St. Anthony and St. Giles on the left and right wings. In white paint, Bosch added his signature "Jheronimus bosch" to the bottom of the central panels of both works.

Sometime in the nineteenth century, cradles were applied to the backs of the Baltic oak panels to prevent warping. "People thought it was best to force the panels flat, but it caused more problems," says Antoine Wilmering, Senior Program Officer at the Getty Foundation. The cradles were damaging the paintings, preventing the natural movement of the wood to changes in humidity -- made worse by climate change. With a grant from the Getty Foundation's Panel Paintings Initiative, a team of Italian and Dutch conservators led by Roberto Saccuman stabilized the two triptychs. The restrictive cradles were carefully removed little by little to give the panels room to expand and contract, and fractures were repaired.

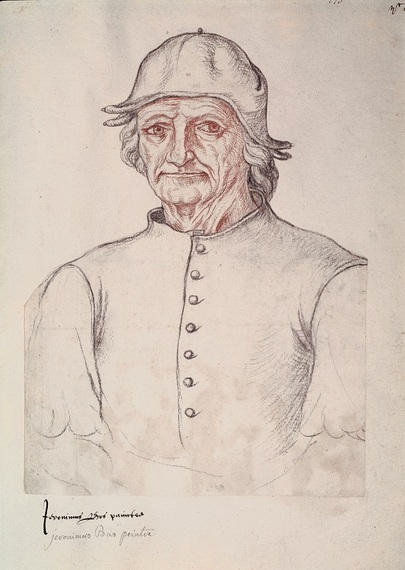

Hieronymus Bosch, Saint Uncumber Triptych, central panel, c. 1495-1505, Oil on oak panel, Venice, Gallerie dell'Accademia. Photo Rik Klein Gotink and image processing Robert G. Erdmann for the Bosch Research and Conservation Project.

Over the centuries, St. Uncumber had been treated at least four times. Now, its flaking paint layers were cleaned and conserved, revealing Bosch's remarkable colors and his talent for painting luxurious gold embroidered costumes. Bosch's subject was also finally confirmed, thanks to micrographs that revealed tiny remnants of a beard on the chin of the martyred woman. As the story goes, after the young woman's father insisted she marry a pagan prince, she prayed to God for salvation and miraculously grew facial hair, making her an unattractive marriage prospect. Her angry father ordered her crucifixion; he's depicted along with her fainting fiancée.

According to Luuk Hoogstede, paintings conservator at the SRAL conservation institute in Maastricht and member of the BRCP team, The Hermit Saints proved the most complex in the project because so much had been changed. "From our research it has become clear that Jheronimus was indeed a genius, highly creative artist, one who utilized the materials so to best convey the message, often changing the composition in the process," says Hoogstede.

Hieronymus Bosch, Triptych of the Hermit Saints, central panel, ca. 1495-1505, Venezia, Gallerie dell'Accademia. Photo Rik Klein Gotink and image processing Robert G. Erdmann for the Bosch Research and Conservation Project.

The central figure of St. Jerome and his cross were originally much larger. Using infrared refractography, the team discovered that Bosch's original donor figures in the left and right wings were overpainted in his studio. At some point, the top of the panels were cropped and strips were added to the bottom.

Fittingly, Bosch's third Venetian work, Four Visions of the Hereafter from Museo di Palazzo Grimani, appears at the close of the exhibition. In four panels, Bosch represents his vision of the end of the world with scenes of reward and punishment. While the blessed are welcomed to heaven by a barely visible silhouette of an angel in a light-filled tunnel, a terrifying cast of monsters pulls the damned toward hell. The original arches at the tops of the panels were also cropped flat.

Hieronymus Bosch, Visions of the Hereafter, ca. 1505-15, Venezia, Museo di Palazzo Grimani from left to right: The Road to Heaven, Earthly Paradise; The Road to Heaven, Ascent to Heaven; The Road to Hell, Fall of the Damned; The Road to Hell, Hell; Photo Rik Klein Gotink and image processing Robert G. Erdmann for the Bosch Research and Conservation Project.

Because the panel surfaces were restored relatively recently in 2008, conservators turned their attention to the backs. Removing old varnish and insoluble dirt, the team uncovered striking imitation red porphyry and green serpentine marble -- reminiscent of Jackson Pollock's drip paintings. "Here, Bosch splattered, blew around and dripped whitish paint onto the black or reddish under layer, followed by green and red glazes, respectively," adds Hoogstede. "It is possible that only these sides were visible for Lent, but we do not know for sure how and in what kind of setup the panels originally functioned."

For detailed images of Bosch's remarkable paintings, see https://www.boschproject.org. For exhibition tickets, visit https://www.hnbm.nl.

The Prado in Madrid also hosts a Bosch retrospective, May 31 to September 11. https://www.museodelprado.es/en/whats-on/exhibition/bosch-the-centenary-exhibition/f049c260-888a-4ff1-8911-b320f587324a

Susan Jaques' biography, The Empress of Art: Catherine the Great and the Transformation of Russia will be published in April by Pegasus Books.