In this era of evidence based science, the practice of medical sciences is expected to conform to standards derived from scientific inquiry. Psychiatry is not exempt from this purported paragon and the American Psychiatric Association publishes and updates guidelines that virtually dictate the parameters of psychiatric practice. These guidelines are based on a body of scientific knowledge that has been assigned the following hierarchy:

- I Systematic Reviews of well controlled Randomized Controlled Trials (meta-analysis) or single RCT with narrow confidence interval

- II Cohort studies or lesser quality RCTs

- III Case- controlled studies

- IV Case series (no control group)

- V Expert opinion

This effort to consolidate and rank medical knowledge is commendable to the extent that it makes it easily accessible to practitioners and informs them of the following;

- What modalities of interviewing, testing and treatment have been proven to be useful.

- Which ones are useful in specific situations.

- Which ones are useless or even harmful.

This allows for a safer and more time-efficient practice. However, with the increasing intrusion of corporate and political influences into the psychiatric domain it is not always the knowledge that best improves patient care that is vested with the most importance. The schematizing and concretion of information has also made healthcare professionals complacent in that the single-minded focus on guidelines is often at the expense of honing clinical skills and ignoring the large corpus of knowledge that does not receive the blessing of specialized journals. This is a trend that begins in schools of Medicine and continues into residency programs and practice. The end result is a formulaic approach that passes the patient through a prism of diagnostic criteria, clinical scales, recommended treatments and insurance coverage limitations. This often results in the patient receiving the treatment that leaves the treatment provider feeling the most satisfied rather than the patient. It also encourages a professional culture that is dismissive of tradition and increasingly divested of the human factor.

Through the requirements of funding, the direction of new inquiry is itself hostage to results from existing studies; one must first peruse vast volumes of existing research and extract from them enough evidence to prove the viability and the usefulness of the study one wants to undertake. This evidence must of course come from studies that fall under the above mentioned categories and are from "reputable" journals.

Most major medical research conducted in the United States begins with an economic endeavor in mind and is affiliated in some way with a corporation. The National Institute of Health provides only a quarter of the hundred billion dollars or so that fund biomedical research every year. The rest comes from pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies with only 3-4% being privately or charitably funded. Financers dictate the methodology and the scope of experiments and investigators have little power to deviate from the objective laid out before them.

Following numerous mergers in the past two decades that gave rise to the pharmaceutical giants, biochemists have found a drastic change in their laboratories-they have discovered that they are expected to be mercenaries more than scientists. Gone are the days of Alexander Fleming, Marie Curie and others like them who had the luxury to put their thoughts into action in their laboratories with little or no intrusion from others. Fleming, who created the medication that has saved more lives than any other in the history of pharmacology, was working alone when he made his discovery. Had he been single-mindedly bent on pursuing the next "block-buster" drug and following guidleines he would have ignored the unwanted fungus in his Petri-dish. He would have thrown the "contaminated" sample out without bothering to investigate the area of inhibited bacterial growth around the fungus.

Such events are not a rarity in the history of medical sciences. In psychopharmacology, most of the original breakthroughs came about either serendipitously or by an individual taking the initiative on his own, such as in the case of the antipsychotic Chlorpromazine and the mood-stabilizer Lithium. Due to its elitist and exclusionary nature, evidence-based science runs the risk of becoming what the French philosopher Michel Foucault called a "regime of truth" and which he described as:

"Each society has its regime of truth, its "general politics" of truth: that is, the types of discourse which it accepts and makes function as true; the mechanisms and instances which enable one to distinguish true and false statements, the means by which each is sanctioned; the techniques and procedures accorded value in the acquisition of truth; the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true"

Pushed to an absurd extent the evidence based construct can become an impediment to progress rather than a handy tool.

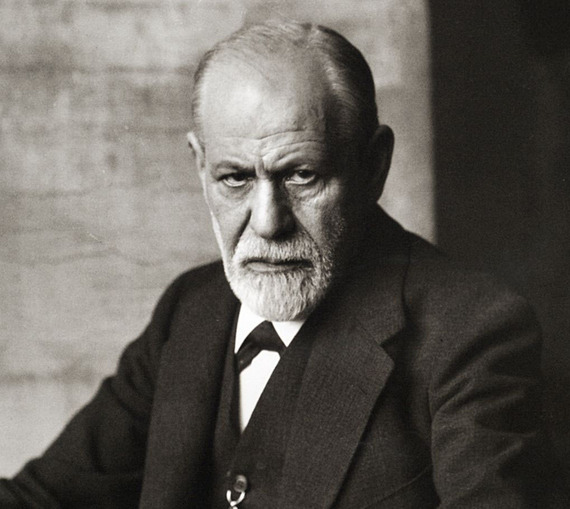

This article is not meant to be a critique of research methods or a call to arms against evidence based practice. To have a set of rules and guidelines is often helpful in overcoming a treatment impasse and avoiding unwanted outcomes. However the stark reality in the domain of mental health is that suicide, frequency of readmission, prolonged use of medication and social impairment have shown no discernible difference. Perhaps it is time to make research findings a facilitating factor in our endeavors rather than let them become blinkers for our curiosity and imagination. We would not be the first ones to admit to this error. We will be following in rather august footsteps. In 1895, Freud wrote one of his most ambitious works; "The Project for a Scientific Psychology". Being among the most accomplished neuroanatomists and neurologists of his time, he meant it to be the beginning of an effort to give all psychic phenomena an anatomical and physiological basis. Having finished it, he did not attempt to publish it (it was eventually published after his death) and wrote to his close friend Wilhelm Fliess that he was;

"not at all inclined to leave the psychology hanging in the air without an organic basis. But apart from this conviction [that there must be such a basis] I do not know how to go on, neither theoretically nor therapeutically and therefore must behave as if only the psychological were under consideration."

Freud was faced with the choice to either continue constructing psychoanalytical theory as he observed it in his patients' and his own inner experience or to try and formulate it only in conformity to a neurobiological construct. Having accepted that the latter was not possible without stunting his ideas, he proceeded with the former and gave modern psychology its foundations. Till today, many of the diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) are based on the descriptions outlined by Freud and subsequent Freudian psychoanalysts.

This now brings me to a fundamental idea that has long been ignored in the scientific realm and which is hard for many to even consider due to the nature of modern education which fragments knowledge under the pretext of specialization and leaves us bereft of the capacity to see the whole picture. Before I discuss this idea itself, let me attempt to prepare the ground for it. Let us examine evolution from the dual perspective of the poet and the scientist.

"First he appeared in the class of inorganic things

Next he passed therefrom into that of plants

For years he lived as one of the plants,

Remembering naught of his organic state so different;

And when he passed from the vegetative to the animal state

He had no remembrance of his state as a plant."

And from the same book,

"I died as a mineral and became a plant,

I died as plant and rose to animal,

I died as animal and I was Man.

Why should I fear Death?"

When was I less by dying?

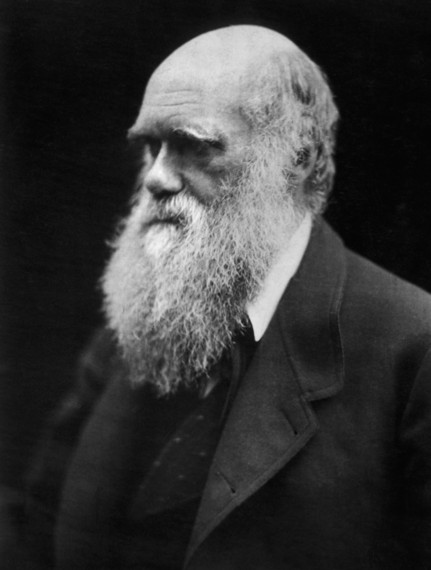

These lines are from the book "Mathnavi "written by the Persian Poet Jalaluddin Rumi over five hundred years before Erasmus Darwin wrote a book entitled "Zoonomia" and almost six hundred years before Erasmus's Grandson, a certain Charles Darwin, wrote "The Origin of Species". Rumi received an education that was imbued in the mystic tradition and emphasized meditation and reflection. His instruction on the workings of nature came from the dervish Shams Tabrizi who constantly advised him to release his imagination from all constraints.

Now, a passage from "Zoonomia";

"Would it be too bold to imagine that, in the great length of time since the earth began to exist, perhaps millions of ages before the commencement of the history of mankind would it be too bold to imagine that all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament, which the great First Cause endued with animality, with the power of acquiring new parts, attended with new propensities, directed by irritations, sensations, volitions and associations, and thus possessing the faculty of continuing to improve by its own inherent activity, and of delivering down these improvements by generation to its posterity, world without end!"

And now Darwin, from "The Origin of Species"

"Probably all organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form, into which life was first breathed. There is grandeur in this view of life that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved."

While most Rumi scholars would agree that it is a spiritual rather than a physical evolution that Rumi was describing, is it possible to deny the parallels in the visions of these three great men?

The idea I spoke of above is this: that more often than not the ephemeral wisdom of the philosopher, the artist and the mystic has presaged by eons the theories of science. Aristotle's "Physica" and "De Anima" would hardly pass the rigorous scrutiny for evidence based knowledge today. Aristotle speaks of the philosophical principles underlying the behavior of matter rather than the physical. Yet without those two books it is hard to imagine that modern physics or modern psychology would exist. What was once poetry is now science; what was once metaphysics is now physics; what was once science fiction is today science.

This does not mean to imply that we should abandon modern science, nor that we should rely on fiction and ancient wisdoms to treat our patients. The point is that we continue to face the same choice that Freud did after failing in his "Project". The first path we can take is to operate mechanistically and let our interaction with the patient be a mere filling in the blanks of reaching a diagnosis and a treatment plan that conforms to the latest available evidence. The second, which is "the road less traveled by", is to immerse ourselves in the subjective experience of the patient and make our own observations and conclusions without incarcerating our natural curiosity and our imagination. We must do so, of course, only after we are good clinicians and understand the science and know the "evidence". But in doing so we can move beyond being automatons content with a status quo of failure and become the innovators that psychiatry so desperately needs. What requires no evidence to proclaim it is the power of the human mind. All knowledge has risen from it.

I do not believe we have fully harnessed the potential of what transpires in the "dyad" of the patient and the therapist. We do not have to wait for the day that we can witness every electrical impulse, every transfer of energy, every shift of blood that underlies what change for the better we may be able to facilitate. Opening our own minds to the subjective experiences of others and working with them to unravel the knots that are psychological conflicts must not become an abandoned art. On the contrary, we must work to improve it and bring it formly into the "scientific" realm.

The inner world of the patient is what gives an existential shape and form to the pathology. By ignoring it we limit both our understanding of mental illness and the extent to which we can help others.