San Francisco Chinatown: A Guide to Its History and Architecture: Introduction

The arrival of the Chinese in the United States toward the end of the 1840s was part of an intricate political and economic relationship between Asia and America.

From its birth as a nation, the United States sought to establish itself as a new power among old nations. Many Americans believed in the concept of "Manifest Destiny," which held that the United States had the right to expand westward across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. The West Coast would be the gateway through which America would acquire and hold the positions of power in Asia.

On the West Coast, in California, San Francisco became not only a major commercial port but also the main port of entry for Chinese immigrants, who were recruited as a source of mass labor for the economic development of the western frontier. Initially, white Americans welcomed Chinese participation in San Francisco's civic events, such as the celebration, at Portsmouth Square, of California's admission into the Union in 1850. At the time, the Square was the heart of San Francisco. However, while the City expanded, the Chinese stayed in the area. For over a century and a half, Chinatown has remained in this same location.

The interaction between Chinatown and the community at large has not always been one of mutual understanding. Caught in the struggle between the white laboring class fighting for better working conditions and the industrial capitalists seeking to 14maintain the status quo, the Chinese became scapegoats for the growing pains of the American labor movement in the West. Sinophobia in the 19th century echoed into the 20th century with the cry "The Chinese must go!" The question of Chinese labor competition occupied a central place in the Nation's politics for over 30 years, until the passage of the Exclusion Act of May 1882, which in effect closed the door to Chinese immigration.

The interaction between Chinatown and the community at large has not always been one of mutual understanding. Caught in the struggle between the white laboring class fighting for better working conditions and the industrial capitalists seeking to 14maintain the status quo, the Chinese became scapegoats for the growing pains of the American labor movement in the West. Sinophobia in the 19th century echoed into the 20th century with the cry "The Chinese must go!" The question of Chinese labor competition occupied a central place in the Nation's politics for over 30 years, until the passage of the Exclusion Act of May 1882, which in effect closed the door to Chinese immigration.

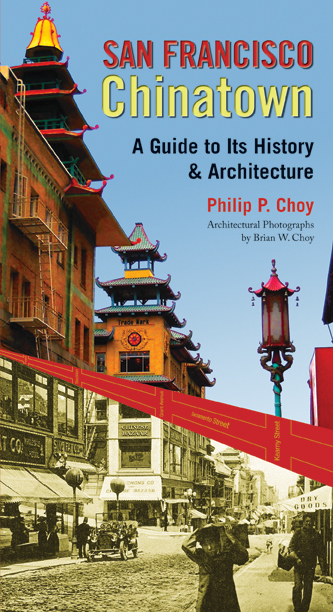

From time to time, San Francisco attempted to destroy Chinatown and remove the Chinese through both legal and extralegal means. The Chinese responded strategically. When the Board of Supervisors attempted to remove Chinatown after the Earthquake of 1906, for example, the Chinese strove to earn the goodwill of the City by creating a new positive image, retaining architects to transform the neighborhood slums into an "Oriental City." This new trend of a Sino-architectural vernacular, created specifically as a response to the threat of relocation after the quake, shaped the present skyline of Chinatown.

But Chinatown has always been a tourist attraction. What was sensationalized in the 19th century as a haven for racial peculiarities and cultural oddities is perceived today as an ethnic enclave where cultural habits and traditions are preserved. In either case, the stereotypical image of Chinatown as an unassimilated foreign community remains unchanged. But the significance of Chinatown lies not in cultural exotics. Beneath the Oriental façade is a history rooted in the political past of the City, the State, and the Nation.

That history began following our War for Independence in 1776. The evidence is before our eyes and under our noses if we know what to look for as we tour Chinatown. Tea, ginseng, and the churches take us back to when two peoples of diverse cultures first met, traded, and interacted. In 1784, when Samuel Shaw sailed the first American ship, the Empress of China, into Bocca Tigrus, he traded twenty-eight tons of ginseng and 20,000 Spanish dollars for tea, silk, porcelain, and other treasures. In his journal, Shaw wrote: "The inhabitants of America must have tea . . . that useless produce [ginseng] of her mountains and forest will supply her with this elegant luxury . . . such are the advantages which America derives from her ginseng" (Quincy 1847, 231). That historic voyage began our interest in the Far East and subsequently led to frontiersmen's hunting and trapping off the California coast for the pelts of sea otters for the Canton market. When gold was discovered, the transpacific commerce between California and Canton (now called "Guangzhou") continued, not only with the importation of Chinese goods for the Gold Rush population but also with the arrival of Chinese laborers from the Pearl River Delta, centered on the City of Canton in Guangdong Province.

From the time of their first encounter in the 16th century, Western nations were determined to open China's ports to trade. Equally stubborn, China called herself the "Middle Kingdom" (i.e., the center of the world) and attempted to close her doors to the "uncivilized, meddling, barbarians." By the time of Shaw's arrival, China had been con-16quered by the Manchu from Manchuria, who ruled under the title "Ching" (brilliance) from 1644 to 1911. The Manchu adopted Chinese ways and appointed collaborators in government posts to maintain control over the population. After two and a half centuries, the Manchu had been absorbed into Chinese culture, except for the Manchu style of dress and the shaven head with the queue (pigtail), which were forced upon the Chinese as symbols of subjugation.

In 1757, the Manchu Emperor Chien Lung (1736-1796) restricted all foreign trade to one port, the City of Canton. Trading between the Chinese and Europeans was controlled and regulated by Chinese merchants known as Hong, authorized by the Imperial government. Unfair practices, import and export taxes, and the demand for silver in payment for goods created trade deficits among foreign nations doing business in China. To offset the deficits, these nations smuggled opium into China in large quantities. The British, whose merchants had control of the supply from India, dominated the trade. American merchants obtained their supply from Smyrna, Turkey. China's attempts to stop the smuggling resulted in war with Great Britain (1839-1842). The British easily defeated China and forced its government to open the ports of Canton, Shanghai, Ningpo, Amoy, and Foochow. In addition, the territory of Hong Kong was ceded to England for 100 years.

In the last quarter of the 18th century, glowing accounts published on the exploration and adventures in the South Seas, India, and Africa, not only 17fired the imagination and curiosity of the public but also aroused the evangelical impulse of Protestant leaders, who founded missionary boards and societies to recruit and send missionaries into the heathen world. While British and American merchants opened the doors to the treasures of "Cathay" (China), European and American missionaries envisioned opening the door to the Kingdom of God for China's three hundred million "heathens." This missionary enterprise was a part of the Christian revivalist movement known as the "Second Great Awakening."

At the beginning of the 19th century, this Protestant religious movement led to the founding of Dr. Morrison translating the Bible with Chinese converts, 1820.18the London Missionary Society (LMS), followed by the founding of the American Board of Commissions of Foreign Missions (ABCFM). In 1807, the LMS sent The Reverend Robert Morrison to China and, in 1830, the ABCFM sent The Reverend David Abeel and The Reverend Elijah Bridgman. Canton became the staging area for Protestant missionary activities. These religious activities, together with the long period of commerce with China, promoted knowledge of the West in China, and linked Canton to California. To the Westerner, the Chinese from Canton were known as "Cantonese." These were the Chinese who would set foot in California when gold was discovered.

Leaders of the evangelical movement quickly realized the strategic importance of California lay not only in the fact that it fronted the Pacific, but also in the unique missionary opportunity the presence of thousands of Chinese afforded; if converted, these Cantonese people could return home to spread the gospel to the teeming millions in China who had never heard the revelation of God. Thus, the many churches in Chinatown today are the result of the efforts of the early Christian pioneers begun in Canton, Macau, and Hong Kong. In San Francisco, the first official evangelical effort took place in a public ceremony on August 28, 1850, when Mayor John Geary and The Reverend Albert Williams invited the Chinese residents to Portsmouth Square to receive religious tracts that were printed in Chinese and published in Canton.

But the fascination with which the West viewed China in the 18th century deteriorated to disre-19spect and disdain by the 19th century. Following its defeat in the Opium War with England, China under the Manchu rulers was on the verge of collapse. Unable to deal with the belligerent demands of Western powers, the government adopted a foreign policy of appeasement, granting concession after concession. Foreign exploitation, internal rebellion, and overpopulation accelerated the decline of China's economy and the deterioration of social conditions.

At the same time, the efforts of the Second Great Awakening that had brought Protestant evangelists to China also hastened the end of the African slave trade, creating a worldwide shortage of cheap labor. The Chinese from Guangdong Province filled this void. American and British ships carried human cargo under wretched conditions throughout Southeast Asia, Cuba, Hawaii, the American tea clipper Nightingale, breaking through the China coast.Artist: Stan Hogill. Courtesy: Bob Schwendinger20Chincha Islands in Peru, and Mauritius and Madagascar off the coast of Africa. This same cheap labor was the resource by which California was developed.