Beginning in 1994, I began a 14-year project to document an unknown body of folk art found in the cemeteries of the San Luis Valley. The San Luis Valley, one of the largest mountain valley deserts in the world, is located in southern Colorado in the heart of the Rocky Mountains. My photographs and research were published in Grave Images: San Luis Valley by the Museum of New Mexico Press. The book begins with the loss of my young husband, which set me on a journey to try to explain sorrow and death to myself, and for others using visual language. I found comfort in the shared sorrow of the grave images in cemeteries. Simplicity, expressiveness and a transformative use of common materials were found in the most evocative grave markers.

In northern New Mexico and southern Colorado an expressive and distinctive flowering of Christian folk art (santos, retablos, altar screens) lasted close to a century from the late 18th to the late 19th century. However, by the time the San Luis Valley was settled in the 1850s, the folk art of santos making was already on the decline and the larger more demanding altar screens were not made in the Valley. There were only a handful of santeros working in the southern Valley, primarily creating santos and bultos for the Penitente's ceremonies during Holy Week.

The unusual, expressive Christian folk art was made for the cemeteries though continued into and even past the mid-twentieth century. Many exceptional examples were made in the 1930s and '40s. To express faith and remembrance of loved ones, the artisans continued the unusual simplicity of expression. As an example: The grave marker for Benjamin Garcia has: BENJAMIN GARCIA; NACIO DECIMBR, 23-1909; MURIO EN FEBR 27-1953 carved into a hand hewn wooden cross set in an adobe marker. Two doves and two four-pointed stars are incised in simple line form in the white washed surface. Marbles, like jewels, are embedded at key points around the wooden cross -- the blue hues especially striking and poignant. The organic shape of the wooden cross is repeated in the line of the doves.

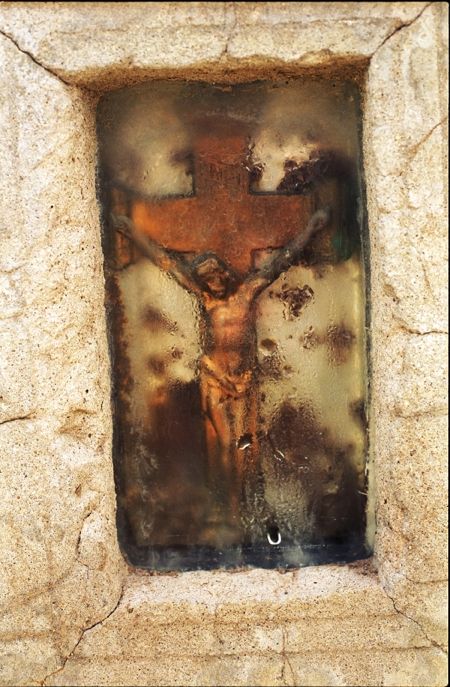

I found that often the focused simplicity reveals profound religious concepts, such as identifying with the Passion of Christ or the Lamb of God. The Franciscan ideals of poverty, charity and obedience, as well as the dedication to Christ and His example of humility and suffering took strong root in the faithful of the desert Southwest. Because of these spiritual values the Penitentes preferred the stark, expressive qualities of locally made statues over the saccharine sentimentality of commercial ones. This focus on the Passion of Christ is found in the cemeteries, showing up in uniquely cut wooden crosses, images of the crucified Christ and the sorrowing face of the suffering Christ.

Additionally, appropriation of materials creates both a visual transformation as well as a transformation of contained content. Use of such materials as shards of glass, marbles, plastic figures, aquarium rock, plastic turf, and bell jars transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary.

Since the beginning of designing my husband's grave marker and photographing the San Luis Valley where I grew up, I have photographed grave images in Colombia, the Family Islands of the Bahamas, Russia, Azerbaijan and Australia.