I'm not sure how it came up, but my daughter, Martha, asked me to remind her what my father's gripe was with medical statistics. My father, a pathologist, leaned on mortality and morbidity data when he worked on committees to establish cancer prevention guidelines. But he wasn't a fan of those very same numbers when it came to talking to cancer patients one on one. As he liked to say, if 99 percent of people with a certain kind of tumor are predicted to survive, that doesn't help you if you are in the 1 percent. Statistics are for the public, not for the person.

We know, for instance, that approximately 95 percent of people who have glioblastoma multiforme, a type of brain cancer, die within two years. Most of us think a death sentence -- and a rapid one at that. But what about those rare survivors?

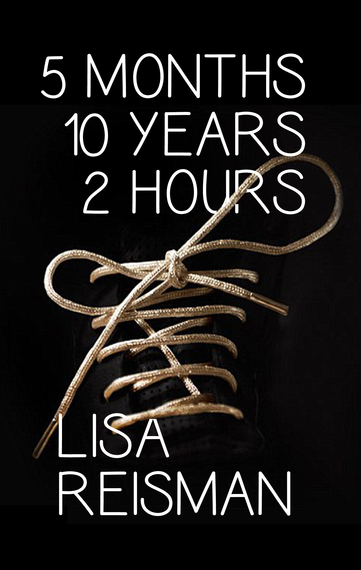

In a remarkable memoir, 5 Months, 10 Years, 2 Hours, Lisa Reisman writes about her diagnosis of glioblastoma, her treatment, and her survival. She was 32 years old at the time, a lawyer who quit her job and planned to get a lipstick-red convertible and tool around the country. Instead, she got cancer.

The book is divided into three sections: Swim, Bike and Run -- because when Reisman realized that she was going to get over this deadly disease, she was determined to finish a triathlon. The writing weaves back and forth between her race and her cancer.

She retells the story of getting sick and diagnosed splashing back and forth with the swimming section, though in real life there's a ten year gap between the cancer diagnosis and the start of the triathlon. She plunged into the ocean and worried that was going to be a fiercer race than she ever imagined.

"Truth was, I was accustomed to being out in front, vying for the win," writes Reisman. "What I dreaded was coming out of the water dead last. Or what would have been grimmer: overexerting myself, growing lightheaded, flailing as the waves engulfed me, calling out for help, the sensation of darkness closing in from all sides. I'd been there ten years before and I wasn't going back. Been underwater, fighting my way toward the surface, my hands and feet tied, holding me down."

Throughout the book, she weaves in her family history, the reactions and help of families members. Cancer, as too many people know, affects not just the patient, but the whole family. "No one goes through the crisis of a serious illness alone," writes Reisman. "There's collateral damage, and it doesn't end with treatments." She said the race was, in part, to prove to her mother that she was not just better but in peak condition.

In the bike section, she writes about enduring the arduous trail and then veers off to talk about the panoply of medications waging their separate campaigns in the wake of her brain surgery. A vegetarian since college, she found herself craving meat. "It was the steroid Decadron that was stirring my lust for sausage biscuits and fried pork rinds and meatball grinders." The pills were adding up: Zantac to prevent stomach ulcers, Bactrim to prevent infections, and another one for the nausea. There were also pills to prevent seizures, to treat headaches, and a slew of stuff to keep her bowels unblocked.

The triathlon was not just a goal, but a cleansing routine.

You read the book and know the ending. After all, she wouldn't have written this if she were too sick to write. And she wouldn't have written her memoir if she couldn't compete in or complete the triathlon. Despite knowing the finale, you keep reading because to read Reisman's story is to read how one woman copes when the statistics didn't seem to be in her favor at all. Her prose is not tinged with clichés or self-pity, but an honest portrayal of coping when life doesn't go the way you planned. Using the race as a metaphor lets us celebrate her dual triumphs as she crosses the finish line.