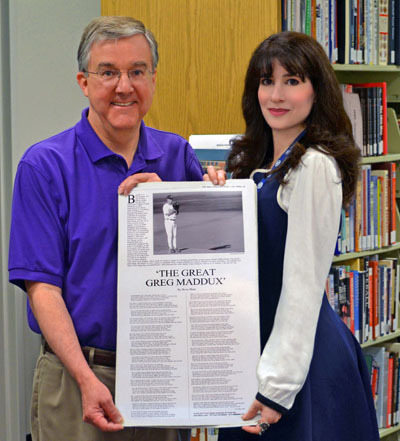

Just beyond the Plaque Gallery of luminaries immortalized in bronze lies the Baseball Hall of Fame's library wherein my poem "The Great Greg Maddux" can be found. It is there that the Hall's library director, Jim Gates, treated me to the sight of my 31-stanza tribute in  verse, leading off the poetry archives. That this presentation was made on the morning of my poem's eponymous pitcher's enshrinement was a special honor. If the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is a treasured destination for fans of our national pastime, its Giamatti Research Center is a diamond mine for students and scholars alike. After viewing my poem and posing for pictures, I couldn't resist getting an inside look at the library from Gates, who is in his 20th year overseeing its vast collection chronicling the life of baseball in literature and lore. After all, my own road to Cooperstown began with research.

verse, leading off the poetry archives. That this presentation was made on the morning of my poem's eponymous pitcher's enshrinement was a special honor. If the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is a treasured destination for fans of our national pastime, its Giamatti Research Center is a diamond mine for students and scholars alike. After viewing my poem and posing for pictures, I couldn't resist getting an inside look at the library from Gates, who is in his 20th year overseeing its vast collection chronicling the life of baseball in literature and lore. After all, my own road to Cooperstown began with research.

I was writing a baseball movie called The Show and several teams opened their  stadiums to me. Learning the game I loved at the Major League level led to my writing several feature articles. One of those, "A Tale of Two Artists," a cover story for the LA Daily News, featured a companion poster of my poem for which I was also asked to write an introduction. The poem is a rhyming recitation of Maddux's many gifts, as told by a bush league skipper warning his star slugger, who's just been called up from the minors, about the ace he'll face in the majors. A letter from Peter P. Clark, then Hall of Fame Curator of Collections, graciously asked me to donate my poem. After the Accessions Committee unanimously voted to acquire it, I received a letter from Jim Gates welcoming my poem into the Hall library's poetry archives and Maddux file. An invitation to Maddux's induction became part of the celebration. What follows is my conversation with Gates about how the library amasses its timeless holdings, the permeation of America's Game in a global culture, the science of preservation and the perils of blue ink:

stadiums to me. Learning the game I loved at the Major League level led to my writing several feature articles. One of those, "A Tale of Two Artists," a cover story for the LA Daily News, featured a companion poster of my poem for which I was also asked to write an introduction. The poem is a rhyming recitation of Maddux's many gifts, as told by a bush league skipper warning his star slugger, who's just been called up from the minors, about the ace he'll face in the majors. A letter from Peter P. Clark, then Hall of Fame Curator of Collections, graciously asked me to donate my poem. After the Accessions Committee unanimously voted to acquire it, I received a letter from Jim Gates welcoming my poem into the Hall library's poetry archives and Maddux file. An invitation to Maddux's induction became part of the celebration. What follows is my conversation with Gates about how the library amasses its timeless holdings, the permeation of America's Game in a global culture, the science of preservation and the perils of blue ink:

Maza: Everyone at the Hall of Fame's been so welcoming. It's wonderful to finally meet you.

Gates: It's great that you're here, Devra. It was fun when you walked in. We have a lot of poems about inductees in the files, but it's unusual for the author of one to be here on the day of their subject's induction to see it. It's special for me to see the face of someone as they see their stuff in here.

Maza: It's great to be seen, both live and on paper. Thanks for showing it to me in such a memorable way. So what originally brought you to Cooperstown?

Gates: Baseball. I spent 15 years in academic libraries before coming here. This is a lot more fun. I was a professor at the University of Florida and I gave up tenure for this, but there wasn't a lot of discussion when they offered me the job. My wife said, "Yeah, you're going," but she was the one who encouraged me to apply for it anyway.

Maza: It's quite an undertaking, preserving baseball for both rabid fans and future researchers. It's the Hall of Fame's 75th anniversary, but has the library  always been part of it?

always been part of it?

Gates: Yes, it started out as a shelf of books and it has grown substantially since. We have 3,000,000 items in the collection now. That includes books, photographs, recorded media, basically all the documents. There are about 45,000 artifacts and some 100,000 baseball cards in the museum's collection, but our job here is to preserve the history of baseball in American culture. It's actually in the international culture now. We have items in English, Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Dutch, Finnish, Italian, and something in Papiamento from Aruba. We recently acquired a book in Mi'kmaq, which is a Native American language from Maine and the Maritime Provinces. They had a baseball association from about 1900 to 1915. We were told it's a rulebook they published in 1910, but none of us read Mi'kmaq. There is, however, a diagram of a ball field in it, so we're pretty sure that's what it is.

Maza: (Laughs.) That's great. In a way, you're doing what parents and kids do by having a catch; you're passing on a pastime to future generations. It's a game with so many lessons.

Gates: Every year, after Memorial Day, I host a three-day symposium on baseball  in American culture that examines the impact baseball has on our society. Baseball is very intertwined with American history and culture and that's what we save here. I have 850 pieces of sheet music. I have files of baseball in movies and poetry, including yours. We have poems written by members of the media, literature professors, and passionate fans. It's such a wonderful thing that people love the sport so much that they'll write poetry about it. So, you cannot escape baseball in our culture. It's everywhere.

in American culture that examines the impact baseball has on our society. Baseball is very intertwined with American history and culture and that's what we save here. I have 850 pieces of sheet music. I have files of baseball in movies and poetry, including yours. We have poems written by members of the media, literature professors, and passionate fans. It's such a wonderful thing that people love the sport so much that they'll write poetry about it. So, you cannot escape baseball in our culture. It's everywhere.

Maza: It's no doubt influenced my writing. I'm thinking of Ring Lardner's tongue-in-cheek beat columns and Edgar A. Guest's poem, "Speaking of Greenberg," which he wrote in 1934 for the Detroit Free Press. It tells of a Tiger fan's transition from anti-Semitism to admiration. And no one would humor publishing a poem the length of "Great Greg" without the precedent of Ernest Thayer's "Casey at the Bat."

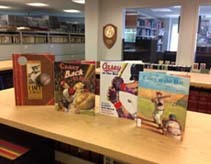

Gates: I have about 500 versions of "Casey at the Bat" here, the original and then there have been all the parodies written since then.

Gates: I have about 500 versions of "Casey at the Bat" here, the original and then there have been all the parodies written since then.

Maza: Willard Mullin's illustrated "Casey" is classic. And Garrison Keillor wrote a "Casey at the Bat Road Game" spoof from the point of view of the opposing team that's a riot.

Gates: My favorite is "Casey's Granddaughter at the Bat," because she erased the family shame when she hit a home run.

Maza: There's a "mighty Casey" babe? I'd love to read that! My screenplay The Show is a comedy about the first female in Major League Baseball, so that's right up my alley. Speaking of which, there's a fun exhibit of baseball in the movies here. I was happy to see Alibi Ike's wacky windup represented. And baseball on radio and TV wouldn't be complete without Abbot and Costello's "Who's on First?".

Gates: We have their gold record of their routine. They presented it to the Hall of Fame on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1956. It's hanging on the wall on the second floor.

Gates: We have their gold record of their routine. They presented it to the Hall of Fame on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1956. It's hanging on the wall on the second floor.

Maza: It's just rewarding to have something in the same building. While "Great Greg" came here through the Curators Accessions Committee, your library also retains my other baseball articles along with documents you deem to be of historic importance. So how are those things processed differently?

Gates: Well, your poem was a donation of intellectual property under copyright, but we are collecting most things in the library, not for display purposes, but for research. It's a completely different mode of operation from the regular museum. We get stuff coming in every day from both the newspapers we subscribe to and writers like you. We also have about 20 to 40 people I call "bird dogs" from all over the country, Canada and Japan sending me stuff.

Maza: Sounds like a lot to sort through. Tell me about the journey to your shelves.

Gates: The library committee gets together every week and reviews the submissions and votes "yea" or "nay." Then, If it's accepted and it's an archival collection, it goes to a processing archivist who will do a catalog record and a finding aid, which is a detailed description for researchers to use when requesting something. If it's just a regular book, our cataloger gets it onto Abner, our library's online catalog, then she puts it on a book truck to be shelved. If it is a file item, then it goes to Danny Bennett, who keeps up the 35,000 files we have here.

Gates: The library committee gets together every week and reviews the submissions and votes "yea" or "nay." Then, If it's accepted and it's an archival collection, it goes to a processing archivist who will do a catalog record and a finding aid, which is a detailed description for researchers to use when requesting something. If it's just a regular book, our cataloger gets it onto Abner, our library's online catalog, then she puts it on a book truck to be shelved. If it is a file item, then it goes to Danny Bennett, who keeps up the 35,000 files we have here.

Maza: So it's a living, evolving thing and no day's work is ever done.

Gates: Right. Every day, new material is going into those clipping files. We keep one on every player in Major League history, all the Negro Leaguers, Women's Leaguers, owners, managers, umpires, announcers, famous fans. Anything where there's a body of literature, we'll open a file. There's also subject files on every country where baseball is played, on stadiums, cities, Hall of Fame events  like this induction weekend. Then we have files on baseball topics such as triple plays, hitting for the cycle, perfect games, and generic cultural files on baseball poetry, baseball and war, stamp collecting, anything baseball related. So media, book authors or academics doing research on a topic can come in and say "I need information on the following" and we'll say "we happen to have a clipping on that." Our goal here is to make things available. We don't want it to gather dust in the basement.

like this induction weekend. Then we have files on baseball topics such as triple plays, hitting for the cycle, perfect games, and generic cultural files on baseball poetry, baseball and war, stamp collecting, anything baseball related. So media, book authors or academics doing research on a topic can come in and say "I need information on the following" and we'll say "we happen to have a clipping on that." Our goal here is to make things available. We don't want it to gather dust in the basement.

Maza: With so many clippings, it suggests the story of baseball parallels the story of newsprint in America.

Gates: Baseball basically became popular when newspapers became affordable and literacy rose, so they kind of grew up together. What you're seeing now is, as the culture and technology changes, sports are changing with it. Now everybody gets stats off the Internet, so projects that would have taken weeks can be done in an hour. On the other hand, people are getting obsessed with data now. I'm not one of them, but we get sent links, too. If it's something we want,  we'll print it out.

we'll print it out.

Maza: I like holding a newspaper in my hands, seeing a full page, cutting out a picture. I'm a big proponent of the keepsake story, the kind you want to tear out and save. It's great that newspapers have archived my articles online, but it's sad that they haven't all retained the artwork that went with them. There are great photographers and art departments whose carefully crafted imagery expands the visceral experience of reading those features. For instance, the photo of Maddux, alone on the mound, casting a long shadow before a pitch, that tops "Great Greg," sets the lyrical tone for the poem.

Gates: But our collection is research-driven, so for our purposes, the text is what matters. The other thing, besides the fact that newspapers are dying, is that baseball has so much more competition. It used to be that there was baseball and boxing. Then the rich would play tennis and golf. Today, with football, basketball, soccer and hockey, there's a lot of competition for the sports dollar, so that's very challenging.

Maza: And as newsprint gives way to interactive media and frame their features for smaller and smaller platforms such as tablets and phones, newspaper size is shrinking along with ad revenue. And the paper it's printed on deteriorates, too, so newspapers aren't just dying, they're decomposing.

Gates: That's because newspapers are made of acid stock. In the production of the paper, they put in magnesium and aluminum sulfates so that the ink sticks to the  paper fibers and doesn't spread out. You know how old newspapers have muddy e's and a's? That's because the ink was bleeding. Now the sulfates they use work very well, except paper is like a sponge. It absorbs H2O out of the air and when sulfate, SO4, mixes with H2O, you get dilute H2SO4 which is sulfuric acid and that breaks down the fibers. You see how this newspaper is yellow? That's an indication that the acidification process has begun. The paper we use for photocopying is called acid-free paper. There's no sulfate in this so it can't go yellow and brittle from absorbing H2O and that means no "slow fires."

paper fibers and doesn't spread out. You know how old newspapers have muddy e's and a's? That's because the ink was bleeding. Now the sulfates they use work very well, except paper is like a sponge. It absorbs H2O out of the air and when sulfate, SO4, mixes with H2O, you get dilute H2SO4 which is sulfuric acid and that breaks down the fibers. You see how this newspaper is yellow? That's an indication that the acidification process has begun. The paper we use for photocopying is called acid-free paper. There's no sulfate in this so it can't go yellow and brittle from absorbing H2O and that means no "slow fires."

Maza: "Slow fires" as in book burnings? That's an ominous phrase to use in a library.

Gates: It's a term used by archivists to describe the slow degradation of paper, but not to worry. Most books today are published on acid-free paper. The way you can tell is you'll see the infinity symbol in the verse of the title page. That means if we take care of that book, it'll be good for 200 years.

Maza: Well, it's nice to be so well preserved. At least your Devra Maza file will never get Botox. We'll have that in common.

Gates: (Laughs.) We'll copy things onto acid-free paper because we want them to be here for future generations. In fact, it's a standard question during our review meetings. We don't look at the value something has now, but we'll say, what research value will this have in 50 or 100 years?

Maza: And you have a couple of centuries to come up with an improved mode of preservation. In the meantime, you have a  lifetime supply of cotton gloves here.

lifetime supply of cotton gloves here.

Gates: They're not needed for clipping files or books, but they are used by researchers handling photo collections and original documents.

Maza: So if we find hieroglyphics about baseball on papyrus, we're good, but my original newsprint articles are still doomed, and there aren't enough white gloves in the world to save them.

Gates: When a newspaper's fresh, you can send it to a conservation lab; for about 100 dollars a page, they can deacidify it. But to photocopy it on acid-free paper costs about five cents. While you can't stop the deterioration process, you can slow it down by putting it in Mylar sleeves which you can get from a reputable archival supply house. Absorption on paper happens when humidity changes, so we store our stuff in six climate-controlled storage rooms and the only time the lights are on are when we go in there. So you need a cool, dry, dark room.

Maza: We have a room like that. We call it the den.

Gates: (Laughs) People collect baseballs and keep them in plastic cases on the wall, but that's the worst thing you can do. You won't find any of those in this building. Plastic cases and bags are made of petroleum-based products that off'gas which degrade materials and cause ink to fade. Artifacts are like people; they need to breathe. I tell collectors to get a dresser and pad the shelves. Put that in your den and when you want to show off your baseballs, let people see them, then close the drawer. Keep them in the dark.

Gates: (Laughs) People collect baseballs and keep them in plastic cases on the wall, but that's the worst thing you can do. You won't find any of those in this building. Plastic cases and bags are made of petroleum-based products that off'gas which degrade materials and cause ink to fade. Artifacts are like people; they need to breathe. I tell collectors to get a dresser and pad the shelves. Put that in your den and when you want to show off your baseballs, let people see them, then close the drawer. Keep them in the dark.

Maza: What about autographs? Any color preference?

Gates: Just don't get autographs in blue ink. Blue standard ink fades faster than black ink because it's more susceptible to ultraviolet light coming out of light bulbs and the sun. But we don't collect autographs here. We prefer things come in unsigned. Then we don't have to worry about it.

Maza: Hmm. When you sent me your letter telling me "The Great Greg Maddux" was being interred in the library, you generously sent me a copy of the poem transferred to acid-free paper. But you signed your letter in blue ink. What do you have to say for yourself?

Gates: (Laughs.) Ha! Well, ink on paper is different from ink on leather and often my letters are not something people are saving for posterity.

Maza: Well, I'll save yours, Jim, if only to balance the scales. Who knows? Maybe some future Hall of Fame curator will ask my descendants to donate it back as an example of their esteemed librarian's legacy.

Gates: That's nice. I like to hear that, too. Thank you, Devra.

Maza: Thank you.

Get the poster of "The Great Greg Maddux" by Devra Maza, read the poem online, or hear the recording of HOF Dodger announcer Vin Scully's reading. To read "A Tale of Two Artists," go here. For more on Devra Maza's screenplay The Show, go here. For more classic baseball poetry, visit the Baseball Almanac. To learn more on the HOF library, inducted members, collections and the history of baseball, visit The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Get the poster of "The Great Greg Maddux" by Devra Maza, read the poem online, or hear the recording of HOF Dodger announcer Vin Scully's reading. To read "A Tale of Two Artists," go here. For more on Devra Maza's screenplay The Show, go here. For more classic baseball poetry, visit the Baseball Almanac. To learn more on the HOF library, inducted members, collections and the history of baseball, visit The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

For more on the author, visit devramaza.com

Photo Credits: Jim Gates and Devra Maza with "The Great Greg Maddux" in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum library, courtesy of Jay Greinsky; Maza's articles, "A Tale of Two Artists" courtesy of LA Daily News, "Curtain Calls" courtesy of USA Today; Alibi Ike one-sheet, courtesy of Warner Bros.; HOF facade, courtesy of Devra Maza; Hank Greenberg card, "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" sheet music, "Casey at the Bat" books, "Who's on First?" gold record, Mighty Casey illustration by Willard Mullin, library glove baskets and Maddux HOF plaque, courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

![]() Take Me Out: What's your favorite baseball movie, book, poem or song? Tell us what's in your Hall of Fame in Comments.

Take Me Out: What's your favorite baseball movie, book, poem or song? Tell us what's in your Hall of Fame in Comments.