La Jolla, Ca.

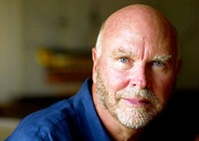

Darwin the poodle bursts into Craig Venter's capacious office on Torrey Pines Road just as he is explaining the meaning of life.

It's digital, life. We are information systems. The chemical elements of our DNA "software" can be broken down into the four nucleotides that make up DNA, "the A's, C's, G's and T's of the biological world," and converted into the 1s and 0s of the computer world, says Venter, 69.

"Once it's in the computer," Venter says, "it can be sent as, uh, email."

Life at the speed of light -- the title, in fact, of his science best-seller.

At the other end of the computer, those 1s and 0s -- digitized life -- can, with the right chemicals, be re-created as real life, a concept that has always had some fuzzy edges, from Leibniz to Schrödinger to "Blade Runner" (original title: "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?")

But it's a concept of great -- if not revolutionary -- commercial potential.

"How we understand our own selves, and how we work with our DNA software has implications that will affect everything from vaccine development, to new approaches to antibiotics, new sources of food, new sources of chemicals, even potentially new sources of energy," he says. "Food will be manufactured -- it won't be grown in fields -- in 50 years."

Already, Synthetic Genomics and the nonprofit J. Craig Venter Institute -- occupied by Venter and his team, which includes the Nobel laureate Hamilton Smith and Clyde Hutchison -- have helped to digitize, send and re-create the newest flu virus, a program in partnership with Novartis.

They are designing and scaling up new protein foods with cells that produce large amounts of heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids. They are working on a new type of antimicrobial agent to combat hospital infections, new ways to purify water and ways to replace plastic -- drinking cups for instance -- with biodegradable sugar molecules.

An algae facility in Calipatria produces the natural food coloring astazanthin used to pink-up farm-raised salmon and shrimp, and the company's deal with Exxon to increase the efficiency of algal cells to make fuel, once valued at $600 million, is ongoing.

But most recently dear to Venter's heart, perhaps, is what he calls the biological transporter, a sort of black box that will be used to decode, well, anything, but right now microbes on Mars.

Though nobody knows for sure, Venter believes a sea runs kilometers below the surface of the red planet and that microbes may exist there that can be digitized on-site, the code sent back to earth and safely reassembled. Call it simply "sample-return," but it has become a big deal to NASA, whose engineers spent days in the Mojave with Venter, who showed up for meetings with his team and a pickup truck packed with beer and Scotch, towing dirt bikes.

Venter -- a motorcycle-racing, world-sailing adrenaline-junkie -- started his scientific career, in fact, by synthesizing the adrenaline molecule from chicken and turkey cells.

"I've always been fascinated with adrenaline; it's saved my life more than once, and it's caused me to need it to save my life more than once," he laughs, adding "one of the most fascinating responses in human evolution, adrenaline sharpens your brain, it sharpens your responses."

He went on to sequence the human genome (taking home the 2008 United States National Medal of Science), and he has now, in his view, created the world's first synthetic life form, defined as a cell "completely controlled only by a synthetic DNA chromosome," which specifies every one of the cell's functions.

He writes, "The science of the coming century will be defined by our ability to create synthetic cells and to manipulate life."

How does he do it?

"I think I have relatively unusual abilities to assimilate complex information that somehow gets assembled in an intuitive fashion. A friend who was also highly intuitive said it was like having a supercomputer running all the time in the background, but you don't know it's there until you see the output of it.

"I also had phenomenal training when I was across the street at UCSD. Nate Kaplan was my mentor, and he had trained with Fritz Lipmann, who got the Nobel Prize for discovering the high-energy phosphate bond, and he wrote a book, 'The Wanderings of a Biochemist,' that I read when I was a student. It talks about how there is anything but a linear route to success in science.

"It may seem a long way to go from the adrenaline receptor, to the human genome, to the first synthetic cell, but they were pretty obvious steps at the time because one led to another, but it's not a straight line.

"I somewhat joke that I know an awful lot because I learn from my mistakes. I just make a lot of mistakes. It's OK to fail in science just as long as you have the successes to go with the failures.

"But I get ideas best from getting away from things and doing another activity. Doing things that require adrenaline requires your full attention. No cellphone use at 130 mph. I used to like that intensity about sailing, too. Sailing requires the full concentration of all your senses, navigating, knowing where you are, dealing with the physical environment. Doing those kinds of intense things frees your brain of the daily garbage and gives you a chance for new insights."

It seems like Venter has more fun than most scientists.

"Science should be the most fun job on the planet," he says. "You get to ask questions about the world around you and go out and seek the answers. Not to have fun doing that is crazy. And I think working hard and playing hard are good approaches. Most people don't work hard enough and therefore don't deserve to play hard enough. Our success -- despite how many good ideas you have -- comes from hard work, and 18-hour days are not atypical for people who work on our teams. Playing hard to blow off the steam from working that hard is not only creative but rejuvenates what you can do. If you don't work so hard, maybe you don't need to play so hard."

Darwin jumps into the lap of Heather Kowalski, director of communications and Venter's wife, and barks that it may be time to go home.

"One last question," I say, "if you looked out 20 or 50 years, what do you think the U.S., the Earth, will be like? Simple question."

"Very simple question!" laughs Venter. "Well, I'm hoping I'm here to help answer that question. The press used to ask me, 'Do you think having the human genome will allow us to live 300 years?' 'It's something that I hope to be able to answer one day, I'd reply.'

"On a more serious note, I've argued that science is no longer something that you do as a hobby or a luxury. For society, it's an absolute necessity.

"If the U.S. is going to be an equally great country in 50 years, it has to pay a whole lot more attention to science and to science education, or 50 years from now we could be second rate. Countries, entire civilizations, are lost in a single generation. We don't pass on our knowledge through our genetic code. We do it through learning and teaching, right? And if you stopped that learning and teaching, the U.S. could go away as a major power in a generation. ...

"If we don't do the experiments, if we don't try and use this new knowledge to solve some of the problems of poverty, of hunger, of disease, it's going to be a pretty nasty world in 50 years, with 4 billion people--more--three times more than when I was born. But I'm an optimist. I think we have at hand tools that humanity has never had before, the tools to truly have control over nature, and if we use those wisely -- and we use them -- the future could be pretty bright."

Darwin barks.