Not long after I lost my brother, a friend passed along an article called "When a Brother Dies," by Judith Newton. As I read, one line popped out like it was scrawled with neon tubing:

Even siblings we don't see, who live differently from us, who move in their own world, may be shoring up our lives, our sense of family, our feeling of being at home in the world without our knowing it.

I could not get this line out of my mind.

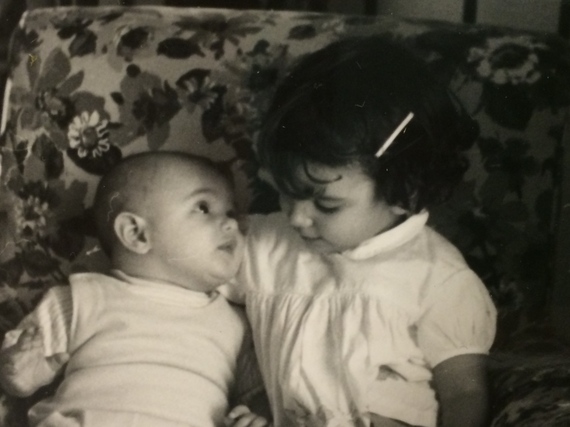

When Frank was born, he completed our family of four. I had just turned two and have no memory of the time before he arrived. As I grew and began to form a picture of what it meant to exist, my brother and parents came into focus first. The rest of the picture gradually built up around and among them. On top of sixteen years growing up together, we lived in close proximity as adults -- we shared an apartment in New York for a while, and later after we married and had children, we spent five years living in neighboring towns, seeing one another whenever we could.

Although we had a strong connection, we did indeed "live differently," traveling in unique orbits with our own colleagues, friends, and communities. Then a few years ago, a job change led him and his family to a new home nearly 2000 miles away. Over the time he lived at a distance, with the demands on both families of work and parenting and life, we generally did not see each other more than once or twice a year.

As a matter of fact, when he died, I had not seen in him in eleven months. Although we were going to get together at my parents over the December holidays, a combination of illness and weather scuttled our plans. We thought we might travel to Frank's for Easter that following spring but he and his wife were going to be away the whole holiday weekend for a wedding, so we figured it wouldn't make sense to come all that way and then not see them.

We were speaking and e-mailing frequently about my parents' upcoming anniversary party, their move to an apartment, work stuff, kid news, and so on, and for that I am grateful.

Then in a blink of an eye he was gone, killed by a drunk driver.

The first few months were a blur of unimaginable tasks, which I performed while feeling numb with shock, as though I were encased from head to toe in a suit made of foot-thick rubber.

"When I began to have a little time to think, I realized that I felt his absence constantly, in every location, at every event, at every moment."

Why? I couldn't figure it out. The pain made sense on holidays and special family days, or at events and places we have shared over the years. But why did I miss Frank at places where I never saw him? Why did I feel his loss at events we never shared together? He wasn't at my house more than three or four days a year since he moved - why did every room seem so empty?

Then I remembered Judith Newton's words and how her brother gave her a "feeling of being at home in the world" in a way she had not realized was happening. Suddenly I knew why I felt the sinkhole of his absence everywhere and all the time, even though he was not physically here everywhere and all the time: The sinkhole is in me. The sinkhole is everywhere I am and everywhere I go, because my home in the world had my brother in it, and now it doesn't.

Photo by Frank T. Lyman Jr.

I see now that this can be a particular burden of someone who loses a sibling, especially a sibling close in age as we were, and especially when the loss comes in adulthood. Something that has been there since the beginning of your consciousness, that you expected to remain throughout your life, is suddenly pulled away. You are left trying not to fall into the sinkhole that is inside your own self, trying to find a way to trust anything anymore. It makes sense to me now, the fact that I took my brother for granted as I do trees, or the sun rising in the morning, or the changing of the seasons. His existence was a daily fact of my life in the exact same way.

"I never conceived of a world without my brother in it. As a matter of fact, to me it makes as much sense for him to be gone as it would for the sun to stop coming up."

I am working now on surrendering to this new world, attempting to understand it, one moment at a time. If you know one of my tribe -- people who have lost siblings -- be kind when we seem confused and unsure of ourselves. Understand that our loss, whether we have been close to our siblings or not, may have made us feel like our home in the world has been firebombed. Support us without judging our loss as less significant than other losses. Maybe help us pick up the pieces of our connections and experiences and form them into a new home. It won't be what it was, but if we take time to create it with love and care, we might find that we can shore up new lives within it.

A previous version of this post entitled After losing a sibling, searching for the sinkhole was originally published on Life Without Judgment by Sarah Lyman Kravits at www.lifewithoutjudgment.com.

This post is part of Common Grief, a Healthy Living editorial initiative. Grief is an inevitable part of life, but that doesn't make navigating it any easier. The deep sorrow that accompanies the death of a loved one, the end of a marriage or even moving far away from home, is real. But while grief is universal, we all grieve differently. So we started Common Grief to help learn from each other. Let's talk about living with loss. If you have a story you'd like to share, email us at strongertogether@huffingtonpost.com.