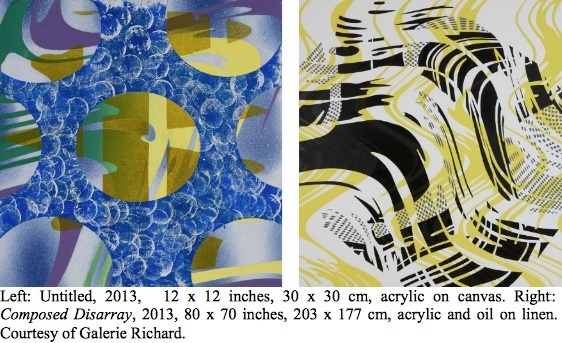

Galerie Richard presents concurrent shows by Shirley Kaneda through May 28, 2014 in New York and Paris. For more information consult the Galerie Richard website.

In Shirley Kaneda's May 2014 show at Galerie Richard, New York, a new context for some well-used formal conventions in painting has been introduced by association with the notion of transparency. Not a literal transparency, as Sigmar Polke made recourse to in the early 1990s by painting on silk. It is more a metaphorical transparency conveyed through the use of high-profile cultural signage, an ingenious mimicry of mechanical reproduction techniques, and a perceptual and conceptual reshuffling of some old formal painterly tropes.

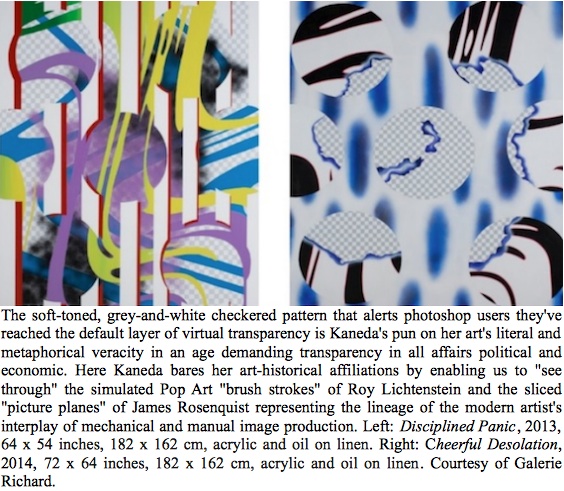

The most salient feature conveying the artists's intention for this body of work is the cultural signage. Photoshop navigators instantly recognize Kaneda's liberal reproduction of the brand's grey-and-white checkered grid, the "default layer" that conveys users have reached a wall of virtual transparency in their project of image making. The software allows images and colors to be posted over the grid in the virtual space, but with the knowledge that any area in which those grey and white squares persist in showing through on the computer screen will in the printing process yield to whatever ground composes the bottom layer, most likely the paper that receives the printed image.

The grand irony at work here is found in a close reading of the work on display, as it becomes obvious that Kaneda is not mechanically producing her art, but manually painting it in the custom of painters for millennia. Her hand painting of the photoshop transparency grid is just one of the ironically-recognizable motifs that function both as a humorous foil for the primacy of paint--that substance which imparts the effect of solidity sufficiently to enable painters to convincingly render physical objects and their reflection of light in the round--and as a metaphor for seeing through the myths, cliches and conventions of modernist painting that have lost their aura over decades of relentless innovation. Transparency, of course, has its own time-honored place in the history of painting. Few inventions in art have been more celebrated than the Renaissance technique of transparent glazing with oils and its sublime expression in sfumato. But as much as Kaneda relishes the history of painterly transparency, she also extends it by finding new uses and meanings for transparency, both as a formal quality in her work, and as a metaphorical reflection on the veracity and knowledge of contemporary civilization.

As for metaphor, Kaneda crafts formal and metaphorical puns that subtly compose multi-layerd labyrinths out of our associative memories, triggering recognitions of media and art history that phase in and out of our viewing experience as our eyes traverse Kaneda's signage of space. The experience in the gallery of seeing the paintings side by side and the full array of Kaneda's lexicon of visualization techniques--each crafted by the artist in mimicry of specific mechanical production techniques--unfolds in a visual process not unlike the shifting view of a kaleidoscope, only laid out schematically and with stability before us. Like a kaleidoscope, the show challenges our memory of the fleeting shapes and illuminations that we've seen before the shapes and illuminations we gaze at in the present--that is, if a present can be truly located, or memorably sustained, among the array of visualizations presented us in the gallery. The exhibition as a whole is a visual barrage that encourages us to selectively see and remember the most familiar motifs and processes--those used by artists of the last century. The photoshop checkered-grid, for example, is signage that even the home-trained artist/designer will immediately recognize as a pun, considering it is unprintable, not truly transparent, and besides, no one really wants to paint that annoyingly ubiquitous default layer signifying something we won't see in the finished photoshop print. But unless we study Kaneda's paintings purposely to survey their formal components and metaphorical signage, we may likely remember seeing more than we do see, so apt is Kaneda's ability to render old techniques in new ways.

Take the most overtly identifiable signage--the motifs familiar from Pop Art. Even among the field of formal cliches at work in the show, Kaneda's Pop Art quotations leap out at us boldly as someone else's invention--though they are just as likely to strike the uninitiated viewer as the most graphically arresting. The more knowing viewers are likely to sound out the names of artists corresponding to their recognitions. What student of twentieth-century art history wouldn't recognize Roy Lichtenstein's bold, melliferous, simulated mock-giant paint strokes? Or James Rosenquist's simulated slices of photographs and billboards levitating at intervals like some gravity-defiant, see-through wall? In fact, in signing Lichtenstein and Rosenquist, Kaneda effects a fourth-generation image (by Kaneda) of a painted simulation (by Lichtenstein or Rosenquist) of oversized brush strokes or a lacerated photograph (found in a book, magazine, or on a billboard overlooking traffic) that has been made by some unknown artist/artisan/photographer to represent a slice of the world.

The double entendre being signed, in its retro-Surrealist-Pop Art-NeoGeo fusion, is just one of the formal and cultural recognitions at work in, and propelling, Kaneda's humorously maze-like process of informing us that perhaps it is time that we, artists and aficionados of art, begin seeing through the tradition of visual-historical quotation that is the art world's version of obsessively-reflexive navel-gazing. After all, painters began manually mimicking mechanical techniques when the French Impressionists and Postimpressionists applied the vivid ocular lessons introduced to them by the Japanese ukiyo-e woodcut artists, and which they translated to the language of oil on canvas. I say perhaps this is Kaneda's message to the viewer because, after all, she is relishing her emersion, first into the archives of mechanical visual production, then into the virtual domain to elaborate cartoons that she then projects, traces and paints by hand onto canvas. And the conversion of literal and metaphorical meanings from one medium don't always translate the same message and relations when converted into a new one. But this too is anticipated by Kaneda, to the extent that it informs her work's elusive raison d'etre.

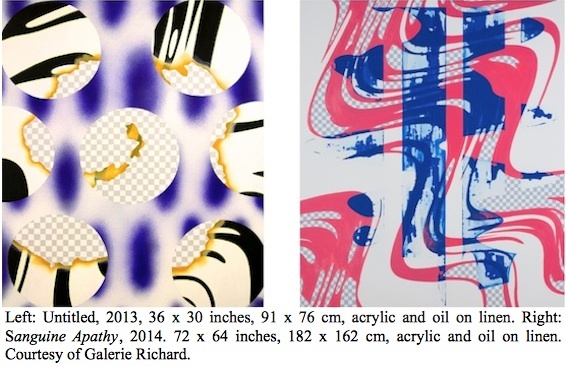

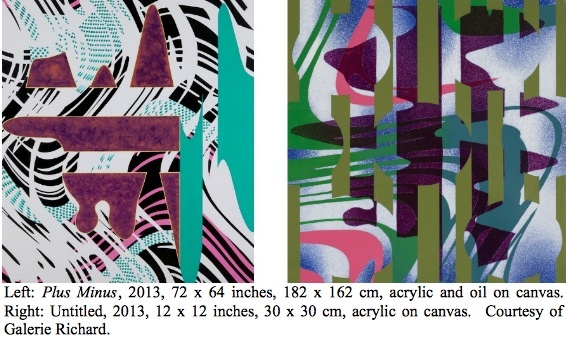

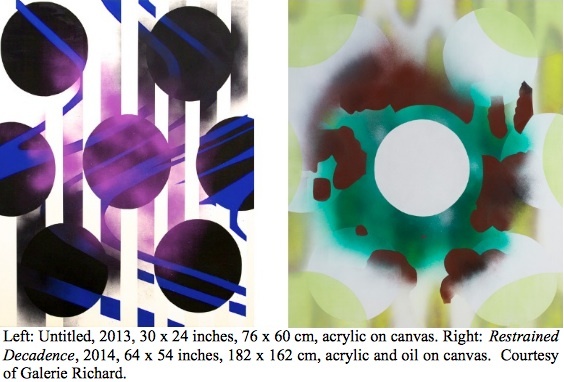

In fact, Kaneda manually simulates the visual effects of an array of 19th- and 20th-century mechanical printing techniques. There are the undeniable hard-edge outlines of stenciling, the ben day dots once so ubiquitously present with letterset and offset printing, the overprinting effect of silkscreening, and the current default grey-and-white transparency grid signifying digital printing. But not really. Kaneda doesn't present us with an image that has actually been produced by a genuine mechanical process. She presents us the deliberate and laborious simulated signage of such processes, the accumulation of which, in effect, becomes a lexicon of the mechanical means by which artists and advertisers in the last century-and-a-half produced imagery for mass consumption. In effect, Kaneda is conducting a dialogue between the mechanical and the manual, the formulaic and the improvisational, the historical and the contemporary.

And what is this lexicon of visual and procedural signage conveying to us? For one thing, it is indicting all the usual suspects of formalist painting and printmaking in one open space, which by itself is a formidable undertaking. My personal survey began with a recognition of the elements of composition: interval, balance or imbalance, figure and ground. There is, of course, color, or its breakdown into hues, tones, gradations. There is determinacy and indeterminacy. There is the illusion of non-perspectival depth provided by the interplay of negative and positive spaces and intuitive positionings. There is the illusion of varying amperages and apparent sources of light: backlighting, underlighting, overlighting. There are painting techniques: sprays, mellifluous flatness, taping, imprints, sponging, gesturing. There is line: undulation, borders, repetition, interval. There is geometry, as often left incomplete and irregular as wholly formed.

But in their suggestion of infinite variation, Kaneda doesn't make such formal variants the determining logic of her work. In opposition to the Modernist painters she by all appearances descends from, Kaneda subjects her formal exercises to the degradations of indeterminacy. Her vivid quotations of Lichtenstein and Rosenquist, for example, neither stand alone nor iconically dominate the compositions when we consider the representation of flux that they are pictorially immersed in. As our esteem of the art historical contributions of the Pop artists erodes with time to make room for current inventions, Kaneda subjects the programmed, impersonal, and isolated signage and techniques of art historical reproduction to the frictions of an idiosyncratic mode of painting utilizing an array of both new and old methods, and if Kaneda feels so inclined, to be combined in some unanticipated, if overly-idealistic, totality.

With the dissolution of art historical paternalism being one of her targeted erosions, Kaneda is to be distinguished from the formalist artists of the past, however much she cites their historical innovations. In no uncertain terms, Kaneda depicts an entirely subjective, imaginary space. It just so happens to be a subjective cultural space that occasions the fond memory of its iconic precedents. This contrasts radically with the formalists who sought to break down the distinction between art and life, sought to overturn the status of an artwork as an illusory subject, by making art a fact consisting of physical realities. But though Kaneda's 2014 New York show conducts our entrance to an imaginary space, it is not an illusory place that we visit, but a perceptual experience we assume to share. Kaneda's painted spaces may derive from the imagination, but their subject is the physical laws of perception to which they must conform and by which they can be shared. It is a subtle difference, one that we articulate into a new phenomenal seeing in the wake of virtual reality. We've come to distinguish the virtual experience as perceptually, phenomenologically, even physically real in the neurological sense, and hence requiring that we name it "virtual" in acknowledgement of the nuanaced experience we today recognize as in between such insufficient designations for art as the "real" and the "illusory".

We may even look back from our age of virtuality at the so-called illusory painting that is said to have been experienced as a window looking out onto the world and question whether art-historically there was ever really such a thing as an illusory painting, a view out onto the world. What sane individual looked at a picture depicting a life-like scene and experienced an illusion of life? (To look like a thing is not to effect an illusion of that thing, but to manifest its sign.) Kaneda, like the virtual artist (remember that she renders every pre-painted composition in photoshop), destabilizes the boundaries between the real and the unreal by restraining her depiction to the formal qualities common and essential to both the experience of reality and the vivid illusion. Like the cgi artist's election of the term "virtual" to mediate the old opposition between the real and the imaginary, Kaneda brings this mediation into the vocabulary of painting and printing, where we can judge for ourselves what of reality and what of imagination survives its replication in a picture, and whether it is salvaged or replicated by the artist, the viewer, or the two together bound by the structure of human cognition.

If this sounds like an exceedingly circular enterprise of the mind, it is because Kaneda willfully defers commitment to any certain topological, ideological, epistemological or ontological underpinning to her art of indeterminate meanings. We can say without reservation that her paintings are empirical, but we must also admit that they are also fantastical. They are meaningful, but with meanings that are elusive. They are rational but unpredictable in their spontaneous improvisations. They are visually articulate but topically mute, which makes them truly paintings to be seen and not heard. No doubt Kaneda feels that quoting histories too explicitly renders us prone to oversimplification. It would also interfere with and over-mediate our reception to her work, which she prefers to be as much a direct and immediate experience to the perceptual encounter as a recognition of her work's cultural citation.

There was a time when such indeterminacy and uncertainty was alluded to as seeing through a glass darkly. But that was a time when even the coinage of metaphors deferred to steeply-buttressed authorities engaged in a tyranny of thought requiring that determinacy and certainty be metaphysically secured to dominate and hold sway over the collective mind. Today, with such devices as heat sensors, ultra-wideband radio frequencies, and x-rays enabling us to visualize interiors physically closed off to us, Kaneda's exemplary imaginative vision of painterly transparency, unleashed in our digital age, can be said to embody an augmented view of the world that facilitates even seeing through solid surfaces brightly.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.