Over the years I've developed a catchphrase for when I'm watching a movie and some poor heroic soul opens the door only to be met by a mob of shouting reporters and flashing cameras: "press as pack of jackals." So imagine my relief upon seeing journalists fully realized as true servants of the public and history in the film Selma, their role in the civil-rights movement honored and celebrated.

There are only a handful of modern films out there that show what being a news reporter is really like -- All the President's Men, Absence of Malice, The Mean Season -- and about a zillion others that perpetuate the image of journalists as heartless predators who harass and misrepresent. Another reason to thank God for Selma.

The part played by the national press, especially broadcast reporters, in bringing to light the realities of racism and the routine brutality of local police and government in the South of the 1960s is well known by historians and journalists, but not necessarily by moviegoers today, so this film is a very welcome primer.

I recently interviewed Richard Valeriani, a former NBC News correspondent and friend who both covered Selma and watched Selma. He himself suffered a head injury just weeks before the March 7 "Bloody Sunday" march across Edmund Pettus Bridge. Here is what he had to say about the film; in true form, he had some criticisms as well as some kudos.

Nancy Doyle Palmer: You were part of the national press that covered the Selma march. Does this film accurately reflect the role of journalists in bringing Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil-rights movement to national attention?

Richard Valeriani: While this excellent film pretty accurately depicts the events in Selma, it does not accurately reflect the role of journalists. And although it does a great job presenting the role of Roy Reed of The New York Times, who did indeed bring the voting-rights issue to national attention, it way underplays the role of television. The film does show the impact of the TV airing of "Bloody Sunday," which was the key factor that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But it neglects the role of TV in general in bringing the events in Selma to the American people nightly. The TV coverage was much more important than the New York Times coverage. In fact, when I called Roy Reed about the film, he was astonished that he had been portrayed so prominently instead of the TV coverage.

N.D.P.: Was it challenging to maintain a professional distance from this story?

R.V.: Not really. Both sides complained repeatedly that I wasn't "helping" them. I constantly explained that I was not there to write editorials but to report the story. I see that as part of journalists' professionalism to remain emotionally detached from the story. I never lost sight of my role as a reporter, not as an activist or an editorial writer. And I think that perspective was not lost on the participants. John Lewis and Andy Young have remained friends for life. The villain in Selma was Sheriff Jim Clark, who was as responsible as anyone for making the campaign successful. The only reporter he would talk to afterward was me. Should I be proud of that? I think yes.

N.D.P.: Did television have a different role and impact than print in the civil-rights movement?

R.V.: There was no way print could capture the drama and the vicious attack on the demonstrators on "Bloody Sunday" the way TV did. I put it on the air with hardly any narrative. I simply said something like, "Civil rights activists demonstrating for voting rights tried to march from Selma to Montgomery today but were stopped by Alabama state troopers. Here's what happened." Then one minute of film, then, "The demonstrators say they'll try again tomorrow." Another thing national TV coverage did was to force local newsmen to be much more honest and accurate in their reporting. The joke at the time was that when there was a demonstration in a small town or remote area broken up by the cops, a reporter would call up the local sheriff to get the story, and he would be told something like, "They kept throwing their heads against our billy clubs." But when TV was there, they couldn't do that anymore, so it forced them to cover more stories in person or go to the scene of the action to get an accurate account. I think this was a very important ancillary contribution of the TV coverage.

N.D.P.: Talk about your relationship with Dr. King and the other leaders at that time and their feelings about reporters.

R.V.: I did not have much of a relationship with Dr. King. He was the face and eloquent voice of the movement. But I had a good relationship with most of his aides, who did the real work: the organizing and recruiting. I learned while I was in the Army that the company clerk knows more about what's going on in the company than the company commander. King and all the others knew the importance of the media in communicating their cause, and they saw reporters as their allies. In The Race Beat, an excellent book about media coverage of civil rights, there's an anecdote about Flip Schulke, a photographer who helped a demonstrator who was being beaten. Afterward King reprimanded him, telling him he was much more valuable as a photographer than a participant.

N.D.P.: You were injured in Selma. Talk about how that affected you as a journalist.

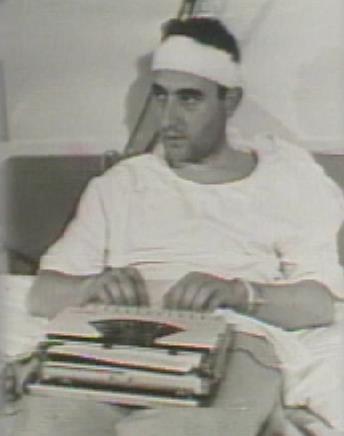

Richard Valeriani filing from his Selma hospital bed on Feb. 19, 1965 (photo courtesy NBC News)

R.V.: As a young journalist I felt like the village idiot. I felt like I could walk into any situation and no harm would befall me. That changed when I started covering civil-rights demonstrations. I used to argue they were more dangerous than covering Vietnam, because the danger in war is random, while it was specific in civil rights. You, as a reporter, were targeted individually, and TV reporters more so, since we were identifiable. On Feb. 18, 1965, I covered a nighttime protest march in Marion, Alabama, not far from Selma, with my NBC colleague Chuck Quinn. We knew nighttime demonstrations were especially dangerous, because TV needed lights, and people knew who we were. When I got there with my camera crew, I knew we were in trouble. Locals sprayed our camera lenses with black paint, and the Alabama state troopers assigned to provide security did nothing to prevent them. Demonstrators emerged from the United Zionist Methodist Church to march to the Perry County jail, where a young civil-rights worker named James Orange was being held. The demonstrators planned to sing hymns and return to the church, but the demonstration was interrupted by Marion police, sheriff's deputies and state troopers, who stopped the marchers and then began to beat them. I was watching this and making notes when somebody came up behind me and hit me with an ax handle. I staggered, but before I could fall, my cameraman held me up. I remember a state trooper saying to the assailant, "You've done enough damage with this tonight," but he did not arrest him. A white man came up to me and asked if I needed a doctor. I put my hand to the back of my head and looked at it; it was bloody. "Yeah," I said, "I think so." The man thrust his face up to mine and said, "We don't have doctors for people like you." I don't remember anything after that, but I was told an ambulance came and took me to the local hospital in Selma. Quinn came the next morning and interviewed me, bedside, for The Huntley-Brinkley Report. The beating got widespread coverage. I got a telegram from Vice President Hubert Humphrey, and telegrams and phone calls from civil-rights leaders and others all over the country. The most shocking aspect of this incident for me came a couple of weeks later. After a few days of recuperation, I had returned to Selma to cover the demonstrations there. Two days after "Bloody Sunday" a lynch mob attacked a [Unitarian Universalist] minister named James Reeb, who subsequently died of his injuries. It had a really serious impact on me. The guy who hit me swung roundhouse, so that he hit me in the thickest part of my head. (Lots of jokes about that ensued for quite a while.) The guys who hit Reeb swung overhead, fracturing his skull. If I had been hit the same way, I would not be writing this today.

N.D.P.: Do you have anything to share about what it was like to watch Selma?

R.V.: Watching Selma was enjoyable for me, since it brought back memories of a significant period in my life. The killing of Rev. Reeb made me think again that I was lucky to be alive. The journalist in me was on the lookout for the flaws (all minor). Essentially, they got it right.

Valeriani and NBC's Ron Nessen at the steps of the state capitol in Montgomery at the conclusion of the march