Born in the Mekong Delta in 1932 to a wealthy land-owning family, Thi Quang Lam spent 25 years in the army and rose to the rank of lieutenant general in the Republic of Vietnam by the time the Vietnam War ended. In Vietnam, he obtained a French baccalaureate in French philosophy and later, in the United States, an MBA. During his military service, he was awarded the Vietnamese National Order, The U.S. Legion of Merit and the Korean Order of Chung Mu. He currently lives in Fremont, Calif. He talked to his son, Andrew Lam, an editor with New America Media.

For Victor Hugo, the famous poet and writer who was a great admirer of Napoleon, the 19th century had only two years. Ce siecle avait deux ans! [This century had only two years.] In those two years, peace was established in Europe and France reigned supreme.

If I could borrow from the great French poet, I would say that for a great number of young men of my generation, the 20th century had only 25 years. Why? From 1950 to 1975, which covered my entire military career, I participated in the birth of the Vietnamese National Army. I grew up and participated with this army that achieved some of the greatest feats in contemporary history, during the Viet Cong Tet offensive in 1968 and during North Vietnam's multi-division Great Offensive in 1972. My career and the careers of my comrades-in-arms abruptly ended in 1975 with the army's tragic demise.

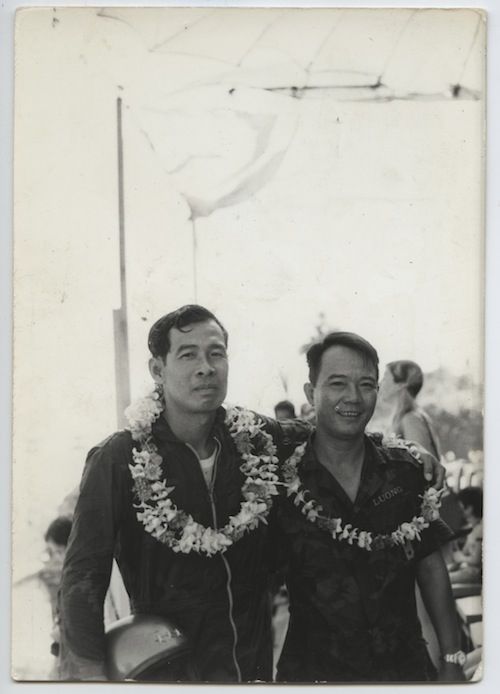

In 1966, when I was 33, I was one of the youngest in the army to become a general. At 39, I became a lieutenant general and was promoted to commander of an Army Corps Task Force along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). I was 43 years old when the war ended.

General Thi (left) in Hue in 1973.

I left Vietnam when Saigon fell in 1975 and joined my family who fled a few days before me in America, got an MBA a few years later, and became a trust officer for Bank of America and raised my family in the suburb north of San Jose. Later on I retired and taught at local high schools in the San Jose area. I taught French, English, Math and PE. I also hold a third-degree black belt in tae kwon do. I still practice at 76, almost everyday, and I go regularly to the gym and play tennis on the weekend and in summer time swim.

After retirement, I was reluctant to write a book about myself. I agree with the French proverb that "le moi est haïssable," [The me is detestable]. But I changed my mind.

The literature in the U.S. regarding the Vietnam War is one-sided. Books written by American soldiers, journalists, historians, and public officials only view the war from the American perspectives while the perspectives the South Vietnamese army, their former ally, was often ignored or worse, portrayed as cowardly and weak, despite the fact that more than a 300,000 South Vietnamese soldiers died during the course of the war as compared to 58,000 American soldiers -- our toll and suffering was far greater than what Americans cared to imagine or know.

Many American journalists were antiwar. The war was presented from the most unfavorable angles with the media sensationalizing the news and distorting the truth if necessary to achieve its antiwar objectives. It is no secret that, for one reason or another, the U.S. media was biased -- if not outright hostile -- to the Vietnam War. They carry that attitude toward looking at the history of the Vietnam War as well.

Even the Vietnamese communists had written quite a few books, which were eagerly translated into English by many American professors, to brag about their military and political achievements after the war. North Vietnam's Gen. Van Tien Dung's "Great Spring Victory," for instance, is widely circulated. Truong Nhu Tang, a former cabinet minister in the Viet Cong provisional revolutionary government wrote "Memoir of a Viet Cong," to tell the story of his life and frustration with the heavy tactics of Hanoi. There's an American fascination with the only enemies who defeated them. Even former defense secretary Robert McNamara went to Vietnam years later to talk and interviewed his counterparts. The South Vietnamese who fought alongside the U.S. army, McNamara never bothered to talk to, and many live near him in the U.S.

Only a handful of books had been written in English by journalists, public officials and soldiers from the former Republic of Vietnam, despite the fact that the largest Vietnamese population outside of Vietnam is here in the U.S.

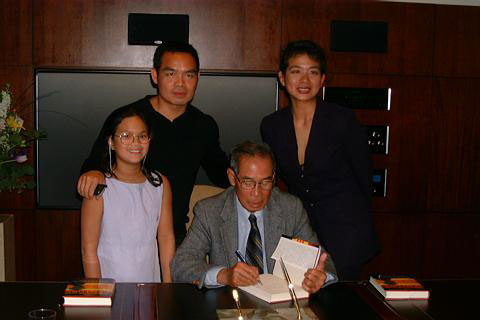

I believe that it was time to set the record straight. That was when I wrote my memoir, "The Twenty-Five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War published in 2000. It was my take on what happened and how Saigon fell.

Two years ago, I'm finished with another. It's called, "Hell in An Loc." It's a less-known battle in 1972 when the communist army attacked from the east, from Cambodia, via the Ho Chi Minh Trail. An Loc, a small town, was defended by 6,900 South Vietnamese soldiers who fought against 30,000 North Vietnamese and 100 tanks. Against heavy odds they withstood 94 days of horror and prevailed at a tremendous cost.

My memoir I dedicated to my grandchildren, Amy, Eric, and Brandon, all born here in the U.S., innocent and with no memories of Vietnam. I wish to leave something lasting and a record of what happened so when they're old enough, I hope they will read and learn something of their heritage.

General Lam signing book with his daughter and son and granddaughter, 2003

The book on An Loc is primarily to tell the South Vietnamese side of what happened and, more importantly, to render justice to their history. These "unsung heroes" have inspired me throughout writing this book and were a source of constant encouragement for me to carry out this at times very difficult undertaking.

I bear the loss of my homeland. So many of my comrades-in-arms died, some committed suicide and many were sent to concentration camps. I feel both anger and sadness. Anger because we were a democracy abandoned by our allies -- the U.S. -- at the darkest hour of our history. But I tell myself that the Indochina and the Vietnam War bought time for the Free World to regroup, marshal its energy and to finally win the Cold War.

If this were not true, then let my work be testimonies to the extent of the devastation and human tragedy caused by unnecessary wars and that my friends and comrades in arms died for nothing.

I get philosophical in old age. I understand that tragedy can strike the best and brightest, and human sufferings have their intrinsic grandeur. I don't expect history to be kind.

I am in exile. America is destination but it'll never be fully home. But I do my best to contribute to the canon of Vietnam War literature, and balance the perspectives of that three-sided war, one in which the South Vietnamese point of view is woefully underrepresented.

Besides I am optimistic. Since the Marxist system is all but collapsed, I still nourish the dream that I will live long enough to have the opportunity to come back to a free and democratic Vietnam.

New America Media editor, Andrew Lam is the author of "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora" (Heyday Books, 2005), which won a Pen American "Beyond the Margins" award and where the above essay is excerpted, and "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres." His latest book, "Birds of Paradise Lost," a collection of short stories about Vietnamese immigrants in the West Coast struggling to remake their lives after a painful exodus from Vietnam, has just been published.

He has lectured and read his work widely at many universities.

Follow Andrew on Tumblr.

For more by Andrew Lam, click here.