The profession and image of architecture both are used against women.

Ghost in the Machine. Elenberg Fraser, Premier Tower, Melbourne, Australia. Beyoncé, Ghost music video.

Sexism takes many forms in architecture.

Possibly the most common is the profession's discrimination against women. While nearly half of architecture school students are women, their numbers quickly drop off after graduation. Among practicing architects, men still outnumber women four to one, and they receive nearly 28 percent higher pay, according to reports. A 2014 survey showed that over 60 percent of women feel the building industry doesn't accept their authority, and two thirds have experienced some form of sexism in their careers, often on a regular basis.

Women also rarely reap the rewards of the profession. In the century since the American Institute of Architects began awarding its highest honor, the Gold Medal, no living woman has won. The only female recipient, Julia Morgan, who got it just last year, died in 1957, six decades before being recognized. In the previous 20 years, only two other posthumous awards had been given to male architects who each had died only a few years earlier. Among the 40 winners of the Pritzker Prize, architecture's Nobel, only two -- Zaha Hadid and Kazuyo Sejima -- have been women and Sejima shared the prize with her male partner. Notoriously, Denise Scott Brown was snubbed when her partner, Robert Venturi, won in 1991.

These statistics reveal a tragic missed opportunity, since, as Kira Gould and I show in Women in Green: Voices of Sustainable Design (2007), the industry can significantly benefit from women's leadership.

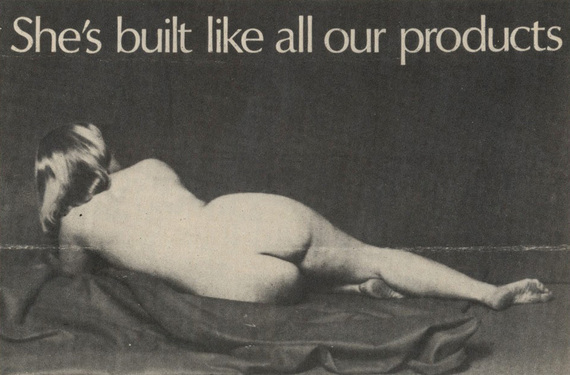

While the profession of architecture discriminates against women, the rest of society objectifies women through the image of architecture. "She's built" is a common expression, and in a 1957 interview journalist Mike Wallace asked Frank Lloyd Wright, "What do you think of [Marilyn] Monroe as architecture?" Replied the architect, "Extremely good."

Vintage ad from Construction News.

Feminist theory identifies two forms of "reduction": reduction to body (the treatment of a person as identified with her body, or body parts) and reduction to appearance (the treatment of a person primarily in terms of how she looks, or how she appears to the senses). Comparing women's bodies to buildings is a double reduction, and the reverse -- comparing buildings to women -- has always been common among architects.

In the oldest known book on architecture, the ancient Roman Vitruvius described Caryatids -- the famous female-figure columns at the Erechtheion, on the Acropolis in Athens -- as prototypical images of servitude, the architecture of bondage. Vitruvius, of course, was the source of Leonardo's famous drawing of the "ideal" (male) body as a model for perfection in design -- and everything else.

Flash forward two millennia. In the 1970s and 80s, Japanese architect Arata Isozaki routinely employed a special curve -- in chair backs, floor plans and other building forms -- that he traced from the contours of Marilyn Monroe's 1953 Playboy centerfold, which he called "the most perfect curves" and "a symbol of American beauty." Some of his most celebrated work, including the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, simulates pornography.

Wright and Isozaki aren't the only architects infatuated with Marilyn Monroe. In 2012, when the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat gave an award to the Absolute World Towers in Mississauga, Ontario, as the "Best Tall Building in the Americas" that year, the jury observed, "It is perhaps not surprising that the buildings have picked up the local nickname, Marilyn Monroe, with the curvaceous, sexy form an obvious association." The judges all were men.

"The Marilyn Ruler." Silhouette of Marilyn Monroe Playboy centerfold (1953), with Arata Isozaki, "Marilyn" Chair (1973); plan detail of Kamioka Town Hall, Gifu, Japan (1976-78); aerial of Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1981-86).

Now some Australian architects have proposed a new tower for Melbourne that is inspired by the body of recording artist Beyoncé Knowles. According to reports, the "curvaceous" form of Elenberg Fraser's 68-story Premier Tower emulates Beyoncé's form in her recent video Ghost, in which she is seen gyrating under wind-blown veils and writhing inside a clingy bodysock.

Beyoncé's own presentation of her body has been controversial, to say the least, with serious debates about whether she is "a feminist or a sex object." Is she empowering herself by taking control of how her body is displayed, or is she merely propping up existing male power structures? Feminist critic bell hooks complains that Beyoncé and others "can exercise control and make lots of money, but that doesn't equate with liberation." Videos such as Ghost, says hooks, signal "a crisis in feminist thinking" because they falsely claim freedom while serving up the female body for public consumption: "Who possesses and who has rights in the female body?"

Just as the question of how women, particularly celebrities, choose to present themselves remains complicated, so does the architectural cooptation of those images. Is the transformation of Marilyn's or Beyoncé's body into a chair, a city hall, a museum, or a skyscraper merely artistic inspiration, or does it signify something more sinister, the literal objectification of women?

The lyrics of Ghost explore the boundaries of the personal and the public, the intimate and the institutional. The singer equates sex with display: "The bedroom's my runway." Ironically, the song complains about commercialization and being used by (presumably male) music industry executives, so Beyoncé appears to attack exactly the kind of misappropriation of her image represented by Premier Tower.

The video samples any number of "high" and "low" sexual references, from Madonna's Erotica (1992) to the Biblical veil dance to body bag fetishes and other bondage practices. Transformed into an architectural effigy, Beyoncé becomes a modern-day Caryatid, a shrouded slave girl. Weirdly, while the building references a woman's body, any tall building also is an obvious phallic symbol. "Sometimes a cigar may be just a cigar," writes Will Self in the Guardian, "but a skyscraper is always a big swaying dick" -- an aggressive image of power that "reduces the human individual to the status and the proportions of a submissive worker ant." What does it mean to translate the image of a woman into a "big swaying dick"?

Portraying the female body as a phallus is an ancient practice, but it was particularly popular among early 20th-Century Surrealist artists, including Man Ray, Brassaï, Magritte, and Hans Bellmer. Art critic Hal Foster writes that the "woman-as-phallus" image "allows a misrecognition of feminine beauty as phallic plenitude," and French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, an associate of the Surrealists in 1930s Paris, later wrote, "Such is the woman behind her veil; it is the absence of the penis that makes her the phallus, object of desire." Feminist critiques of Lacan expose the misogyny of this image: "For a woman to 'be' the Phallus," explains Judith Butler, "means to reflect the power of the Phallus, to signify that power, to 'embody' the Phallus, to supply the site to which it penetrates...." The phallic woman is the ultimate symbol of submission, and Elenberg Fraser has plucked it out of art galleries, porn sites, and sexual fantasies and inserted in the skyline of Melbourne.

"Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and ultimately, deserves," wrote architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable. Do we deserve skylines populated with fetishistic phallic symbols? Emulating women's bodies in architecture objectifies women, but it also objectifies architecture, reducing buildings to mere totems, ciphers reminding us who is in power. Using the human body as a model for architecture is as old as architecture itself, but maybe it's time for architects to rethink where they get inspiration.

Architect Lance Hosey's latest book, The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design (2012), has been Amazon's #1 bestseller for sustainable design. Follow him on Twitter: @lancehosey