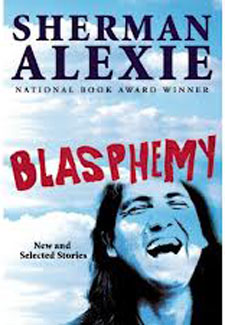

Blasphemy: New and Selected StoriesBy Sherman AlexieGrove Press480 pages

________________________

Don't go calling Sherman Alexie's stories universal. "When people say universal they mean white people get it," he argues. His assessment is even more damning when you consider his subject matter -- modern-day American Indians. If there's any group white people get, this is not it.

But scan through the themes recycled in Alexie's stories (loneliness, grief, depression), and universal would seem an obvious word choice, one selected by approving reviewers with the best intentions. Alexie is partially to blame for the confusion here. Yes, his characters follow such culturally-specific trajectories that their loneliness is probably like no loneliness you've ever known. Where Alexie trips us up is by making such distinct loneliness feel knowable.

Blasphemy, his latest collection of 30-odd short stories, is shot through with an emotional strain that's come to characterize his writing. Equal parts old favorites ("What You Pawn I Will Redeem," "The Toughest Indian in the World, "War Dances") and new additions, it's Alexie's most comprehensive collection to date, and a powerful thwap against mainstream knowledge of American Indians (largely written in cliches from the Dances With Wolves school of learning).

The American Indian PEN/Faulkner winner for 2009's War Dances, Alexie grew up on a Spokane reservation in Washington state, but the stories here concern themselves largely with urban Indians, living with one foot off the reservation, and one foot perpetually in. Alexie tosses them in and around Seattle, with a host of identity issues that come with leaving the reservation, or alternately, never being on it -- rejecting identity, overidentification, guilt at not being Indian enough. ("I suppose if you're indigenous to a place and you're still searching for your identity, that's pretty ironic," Alexie once explained to the Atlantic.) Laying bare the modern Indian psyche, he approaches it by way of his loserish protagonists -- unfaithful wife, accidental murderer, washed-up basketball star who cries too easily, alcoholic father, 7/11 worker -- many of whom represent exaggerated pieces of his own personality. Their stories are all distinct and self-contained, but together they impress a strong sense of mood, a sadness that drifts from one into the next.

Strangely, amid all these downers, Alexie is able to keep your spirits up by toggling between sorrow and humor, and skillfully crisscrossing the two. "Lonely and laughing" is the sort of image evoked often in his characters, who wobble between sanity and madness. The laughter keeps them sane, the loneliness drives them mad, and sometimes, you're not sure which is which.  Grief is a trickier beast to laugh off ("Mr. Grief always wins," we're reminded), and it's what pushes Alexie's characters fully into madness. In "Breakfast," a son cracks an egg and sees his father's "impossibly small corpse" floating in the mixing bowl. In "Salt," a senile widow thinks pouring salt on her husband could return him to her. As crazy as his grief-driven imagery is, it bristles with realism by meeting his characters' pain at eye-level.

Grief is a trickier beast to laugh off ("Mr. Grief always wins," we're reminded), and it's what pushes Alexie's characters fully into madness. In "Breakfast," a son cracks an egg and sees his father's "impossibly small corpse" floating in the mixing bowl. In "Salt," a senile widow thinks pouring salt on her husband could return him to her. As crazy as his grief-driven imagery is, it bristles with realism by meeting his characters' pain at eye-level.

For every grieving widow, you also have a compulsive joker who is full of tumors ("my favorite tumor is just about the size of a baseball"), a cop amazed by a homeless man's good humor ("You Indians. How the hell do you laugh so much?"). Alexie's heroes are losers in the most expansive sense of the word, and by making them laugh, he nods at how his culture has often responded to losing.

Toward the end of this 480-page collection, these heroes begin to wear a little thin. But for the most part, each story is a page turner, the longest hitting 57 pages, and the shortest falling just under one. Long or short, Blasphemy's stories feels like a series of literary sprints, each one quickening your heart rate and leaving you pausing to catch your breath before you're on to the next.

This story originally appeared in Literary Issue of Huffington, in the iTunes App store.