Sunday Oct. 25, 2009 will mark the sixth anniversary of the arrest at gunpoint of the Russian political prisoner Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Over these long years in which he has been illegitimately, unlawfully, and brutally held in a Siberian gulag between two show trials, I've seen both my client and his country undergo important changes.

It sometime seems like a distant memory, but back in 2003 it was still possible to speak optimistically about the future of Russian democracy and civil society. For example, a few weeks before Khodorkovsky's arrest, Steven Lee Myers of The New York Times interviewed one source who, like many, saw Russia standing at a crossroads: "there were in fact two Putins: a security agent and a democrat, struggling for equipoise."

Nowadays most observers would agree that the scale tipped a long time ago, with all public institutions coming under the control of business-owning former security officers. Even Mikhail Gorbachev himself has described the latest irregular elections as "a mockery of democracy."

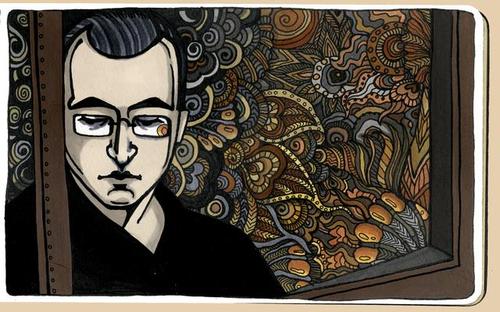

Artwork is copyright of artist Katya Beliavskaya, credit to "Drawing the Court"

Artwork is copyright of artist Katya Beliavskaya, credit to "Drawing the Court"

The hammer of authoritarianism has come down hardest on journalists, oppositionists, NGOs, and human rights activists in the years since Khodorkovsky's imprisonment. One of the philanthropic projects he supported, the Open Russia Foundation (a George Soros-like pro-transparency organization), was raided by the police continuously after his arrest before a forced closure in 2006. The journalist Anna Politkovskaya and the lawyer Stanislav Markelov have both been victims of Russia's system of impunity. Other NGOs, such as Memorial, have had to severely constrain their operations in recent years to pressure from the Kremlin. Following the horrifying murder of activist Natalya Estemirova this past July, Memorial was recently the Sakharov Prize by the EU parliament - though this honorable recognition has done little to get the Kremlin to remove the boot from the organization's neck.

Khodorkovsky himself has undergone both a physical and symbolic transformation. These years spent in harsh prison conditions, where he has been punished repeatedly for invented offenses like possessing lemons or drinking tea in the wrong area, have been physically difficult. When art students came to attend the current second trial of Khodorkovsky as part of an independently organized contest, the prisoner himself jokingly referred to the ghostly pallor captured in one portrait.

But it is clear to those of us who have watched and listened to Khodorkovsky over these years that his beliefs, spirit and convictions have only deepened. When he first became a political prisoner, he was recognized as a symbol of Russia being on the wrong track: the disappearance of rule of law, corporate raiding and state theft, authoritarian drift, and the Kremlin's first taste of using stolen assets as an energy weapon. Today, after six long years of injustice, he is emerging as an important political voice and a sign of Russian moral conscience.

These statements have been building over past months, most recently highlighted by an article he penned in Vedomosti, challenging President Dmitry Medvedev's proclamations of reform and liberalism made some weeks earlier. Within the Putin-Medvedev tandemocracy, Khodorkovsky writes that the president is merely "playing the classic role of the 'good cop' in a theatrical performance;" and that when the president speaks about the need for a genuine civil society and a citizen-driven reform process without a rejection of the current authoritarian system, it is only a rhetorical exercise.

A true modernization process in Russia cannot be another top down directive from the inefficient vertical of power, Khodorkovsky writes, but rather a movement pushed by the voices of millions. As Medvedev had pledged to incorporate responses of citizens to his article in his state of the union speech, he told the media recently that he had read Khodorkovsky's article.

Though his views are political, his ambitions are moral, not personal. In a Q&A published on Gazeta.ru, Khodorkovsky writes that he "hopes against hope" that he will soon be released and reunited with his family, to spend time with his children before they have already grown into young adults. He writes that he is "far from being a hero....Today, I am just a prisoner. Nothing more, nothing less." However he entertains no illusions about the political nature of the process being carried out against him: "If it's done according to the law, it should be soon. But it will be when they stop being afraid, that is, never. (...) Russia will always exist and a change of power is inevitable."

In the meantime, the theater of the absurd continues on a daily basis at the Khamovnichesky District Court in Moscow, where Khodorkovsky is undergoing a second show trial in which he is accused of somehow having been able to embezzle the entire oil production of Yukos company - charges that are not only implausible and groundless, but also contradictory of the charges of the first trial. This theatrical performance may as well carry the title "Waiting for Putin," as the desultory prosecutors waste away the days, as the judge awaits the telephone-ordered verdict from above.

As the days slip away into the maw of this judicial travesty, we'll continue counting the missed birthdays, fatherless holidays, school graduations, anniversary dinners, weekends at home, and severed friendships. These deprivations are investing Khodorkovsky's words and perspectives with more and more meaning, and the people of Russia are waking up to it. Isn't it time that the international community begin to do the same?

Robert Amsterdam is a member of the Mikhail Khodorkovsky international defense team.