This post first appeared on RoadsideScience.com.

Adrian Lenardic, a planetary physicist in Rice University's Department of Earth Sciences, was checking his pocket radar when a 10-year-old skateboarder asked what he was doing.

Lenardic, a skateboarder himself, explained that he was testing how fast he could go. The boy asked what the average speed of skaters was at the park. "I said, 'I have no idea,'" Lenardic recalls. "I told him, 'In principle we can do measurements on the range of skaters who come through.' I said, 'You could figure out where you sit compared to the average skater,' and he was fascinated by that."

Lenardic handed over the radar and told the boy to test his own speed. "The boy was in awe that this science guy said, 'Here, you take the instrument,'" Lenardic says. "That's when I started thinking this could be used for education."

When Lenardic first brought a scientific instrument to the Lee and Joe Jamail Skate Park in Houston, Texas, he wasn't interested in science outreach. He was merely trying to survive the sport. When he went back to skateboarding in his thirties after a 15-year hiatus, he found that the techniques he used as a teenager just weren't cutting it. Skating is hard on joints. While young skaters can power through tricks without worrying about aching knees, older skaters must economize every movement or risk injury.

If Lenardic wanted to keep skating, he needed to become more efficient. Being a physicist, he knew something about studying motion.

"Skateboarders generate speed by pumping," Lenardic explains. "When you're

on a swing set, standing up on the swing, you pump for speed by bending your legs up and down at the right time. You're moving your center of mass up and down relative to where your arch is on the swing," he says. "Much like pumping on a swing in a standing position, skaters move their center of mass by alternating between standing tall and crouching low on their boards when they hit transitions -- the regions in a pool or ramp that connect flat sections to vertical sections."

Lenardic wanted to test whether his pumping led to smooth accelerations, or whether he was tripping up his momentum by standing tall at the wrong times. He rigged an accelerometer up to a vest he purchased at a sporting goods store and headed to the park to collect some data. The accelerometer could track the rate of change in velocity as he skated.

As expected, Lenardic discovered that he wasn't as efficient as he could be. In the years that followed, through many chance interactions with curious skateboarders, he also discovered that running experiments at the skate park is a highly efficient way to get skateboarders excited about science.

What Lenardic never liked about science class as a kid, he says, is that, "When you were doing an experiment, if you actually discovered something, it meant you made a mistake. It wasn't an experiment to discover something. It was an experiment to reproduce something that someone had already told you."

For the past two years, Lenardic has been encouraging skaters who ask what he's doing to test their own questions that no one knows the answers to. At the 10-year-old boy's suggestion, Lenardic got a dozen skateboarders together to measure their average speed.

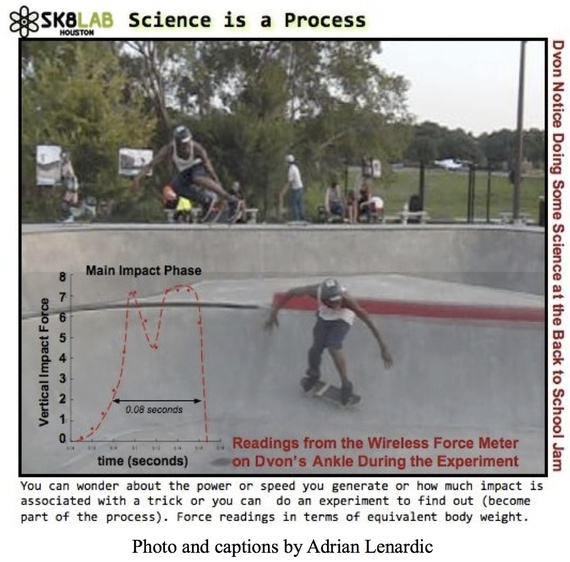

After Dvon Notice, a 24-year-old automotive technician, mentioned to Lenardic that he had always wondered how much impact his legs felt when he landed a trick, Lenardic brought a force meter to the park. Notice attached the meter to his ankle and did a trick where he skated up one ramp, jumped through the air, and then skated down another. He did the trick multiple times and each time his legs touched down, the meter read the g-force. "A force of 2 g is you feeling twice your weight over a short period of time," Lenardic explains.

"I learned that there's a lot more force generated than you may think," Notice says. "I was generating 7.25 g. I put that into Google to see what would pop up and it was close to the g-force a fighter jet pulls. It's kind of crazy that our bodies are feeling that much force when you land."

Lenardic's greatest motivation: "To get people to understand the power of doing experiments." He says he wants skateboarders to recognize that "what they're already doing as they're learning about the world through trial and error is a short jump from doing a scientific experiment."

Lenardic and the other skateboarders have many more experiments planned. They want to know whether the type of shoe they wear affects the force they feel, and how the hardness of the wheels on their boards affects their speed. They want to know which skating parks have the fastest bowls. Notice's last experiment made him want to delve deeper. "I have some more experiments planned to figure out what goes on inside the human body when we skate," he says.

What began as Lenardic's chance encounters with skaters at the park is turning into a full-fledged science outreach program called Sk8 Lab, Houston. There is still no formal way to sign up for Sk8 Lab. Anyone who happens to be at the park when a project is going on is welcome to join in.

But they are becoming a bit more formalized. Last year Sk8 Lab launched its own Facebook page. Sk8 Lab volunteers have started working at large skating events -- once doing live speed readings of skaters in front of a crowd of 300 people. They visit high schools and present at scientific conferences. They have a portable science pack with all of their instruments in it and they hope to develop a system where they have many packs so skateboarders can borrow them to experiment on their own. Lenardic and Notice are even involved in beta testing a new activity monitor from a company called Active Replay that can send acceleration and force data directly to a skater's smartphone. They hope this technology will help them reach even more skateboarders.

Lenardic wants to reach as many people as possible, but he understands that merging science with the skateboarding community takes time. "It took a while for a range of skaters to recognize me at the park, to feel comfortable coming up to me," he says. "Progressively, people have gotten to know me. They start to know what I do and they say, 'Are you that scientist guy?' and I say, 'Yes, I am.' I want to do it organically and let it develop, and if it does, great."

Even as the program continues to grow, at its heart, Sk8 Lab is still about breaking down barriers to science one curious skateboarder at a time.