"For the whole air vibrates with a vast purpose and energy which has been and is no more." ~ Katherine Scoresby Routledge, 1919

Two weeks ago members of the Hito family of Easter Island were forcibly removed from the $50 million Hangaroa Eco Village & Spa, which they had seized last August, claiming the land was swindled from their illiterate grandmother and then passed illegally into private hands during Chile's dictatorship. It was just the latest in a long arc of confrontations between the consanguine of the South Pacific mote, and floating weeds that forever wash onto these shores.

Rapa Nui, the island's official name, is among the most solitary inhabited flyspecks in the world. Eight miles wide and fourteen miles long, its rounded, deltoid-shaped surface is about the size of San Francisco. It sits 27 degrees south of the Equator, fretted by incessant winds, ringed by a million square miles of open sea. Motherland Chile lies over 2300 miles to the east. The closest inhabited place, almost 1200 miles to the west, is Pitcairn Island, settled in 1790 by the mutineers from the H.M.S Bounty. To the north, a vast desert of Pacific Ocean; to the south, the Austral Seas as far as the glacial coasts of Antarctica. The nearest solid land the islanders can see is the moon.

Its prehistoric residents called it Te Pito-o-Te Henua, meaning "The Naval of the Earth." The Tahitians, who arrived during the 19th century, called it "Big Paddle (Rapa Nui)" which is what it took to get here. But despite the latest totemic rebranding, it is still most popularly known as Easter Island, from the auspicious Sunday when Dutch explorer Admiral Jakob Roggeveen dropped anchor in 1722. Half a century after the Dutch the Spaniards arrived for a brief stay in 1770 under orders from King Carlos III. They found little of interest on the lonesome, raw-boned isle, but they renamed it San Carlos, and half-heartedly annexed it for the Spanish Crown.

Four years later Captain James Cook sailed in to replenish his stock of food and water. There was little of either. The English were amazed at the giant, flat-headed statues with their inscrutable sphinx-like faces and cylindrical ten-ton topknots of red stone balancing on their brows. "It was incomprehensible to me," Cook wrote, "how such great masses could be formed by a set of people among whom we saw no tools."

In 1888 the Chilean government finally annexed the island, without protest from Spain or any other country. As Captain Cook said, "No nation need contend for the honor of the discovery of this island."

The archeological history of the island is as baffling as its various autographs. Shrouded in etiological puzzles, the place continues to pique the minds of scholars and travel show hosts. With over 600 lava-hewn statues and untold thousands of ruins and artifacts, most dating to pre-13th century, the island is the richest, most bewitching open-air museum in existence.

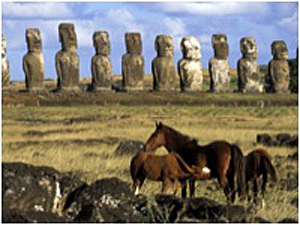

The colossi of rock, Moai, as the islanders call them, are recognized from a dreadful Kevin Costner film to Gary Larson's comic panels to scores of travel features, as the dour, unblinking symbols of the island. In no other place on our planet can such large statues be found in such a small place in such great numbers and created by so few. They stand scattered like pawns in a chess game of the gods, played against the ages, waiting for the next move of a long-hesitant hand.

I arrive from Tahiti, as quondam wayfarers before me. After a breakfast of hard biscuits and Nescafe Instant (the well-appointed hotel insisted no real coffee available--too expensive to import), I shoulder a rucksack with lunch and camera gear and wander outside to something resembling a horse. Some 4000 wild horses roam the island, almost equal to the human population, and the horse is the most common mode of transportation. I am blessed with a relatively tame specimen, and it looks it: haggard, a dull coat, a sagging middle, and tired eyes. But the price is right ($10 a day), so I mount the gunny-sack and sheep-fleece saddle, and with a crude map in hand start loping northwards up the jagged coast.

I first pass through the island's largest settlement, Hanga Roa (with some 3500 inhabitants, it accounts for over 87% of the total population of Easter Island), with its tidy white houses of cinder block or painted wood and tin roofs that serve to collect water. Stopping at the bleached stone library I ask if I can borrow the island's only copy of AKU-AKU, Thor Heyerdahl's account of his 1955 archeological expedition. "Sorry, no lending," the librarian says in Spanish. Just as well, perhaps, as many on the island believe the book is more non-fact than non-fiction. After six expeditions to Easter Island, including one in 1986 during which he uncovered ancient ceremonial constructions, human teeth and bones, soil containing charcoal, and stonework similar to that found in pre-Inca sites, Thor stoutly phonated that the island's first inhabitants arrived from Peru around 800 B.C., traveling in balsa-log rafts, such as the one he sailed from Peru to Polynesia in 1947, the raft he called Kon Tiki.

But most of the Pascuenses, as the islanders call themselves, cling to the belief that their ancestors came from Polynesia. Many reputable archeologists and other scientists agree, refuting the "daring Viking's" notions as self-serving and romantic. Those who take issue with Heyerdahl believe the evidence is strong that Easter Islanders settled around A.D. 400, arriving from islands within Oceania. Besides similar racial and language characteristics, they cite ancient carved symbols on the island also found on art objects in other parts of the South Seas.

Less than three miles up the coast I canter across a fawn-colored meadow, flushing hawks to flight. Then I crest a ridge and stop in my steed's tracks. There, out of the dusk of centuries, silhouetted against a shimmering expanse of sea, looming above, are the five massive brooding conundrums called Ahu Tahai.

More impressive than Stonehenge or Carnac, these mute monuments have spawned theories of origin from the plausible to the preposterous: architects from the lost city of Atlantis, ancient astronauts from deep space, South Sea spirits that walked onto the beach and froze, the art of Incan sailors, and on. Not one of the Easter Island faces is smiling, so they are not, it must be assumed, from Bhutan.

The statues range from nine to sixty feet in height and from three to one hundred tons in weight, and are scattered around the island pell-mell. There are virtually no trees on the three-million year old volcanic mote, so there is no wood to fashion into wheels or rollers or levers. It seems incomprehensible that a people who had no natural means of leverage or traction could make, lift, and move these creations without supernatural or extraterrestrial assistance.

Where did these people come from, where did they go, and how did they move these hulks of stone?

Thor Heyerdahl posited the carvers from South America. The resemblance to ancient structures in Cuzco is indeed uncanny, and Cuzco in the Incan language means "navel," as in the islander's early name for their home.

But the more accepted ethnographic explanation depicts a migration from the Marquesas Archipelago bringing, in great outrigger canoes, a population of gifted sculptors to the island, perhaps as early as the seventh century. Oral tradition tells that the statues were intended as tributes to ancestors, and that ingenious methods were devised to transport and raise them. Most were made of volcanic rock found in the tuff quarries of Rano Raraku, on the southeastern coast, and were fashioned by stone chisels made of obsidian.

A second migration from Mangareva in the Gambier Islands, 1700 miles to the north, brought a less creative, more agriculturally inclined group, who, it has been guessed, at some point clashed with the Marquesas emigrants and wiped them out.

There is another, more recent, theory as to why people stopped carving these statues, one that upsets some anthropological applecarts. Notwithstanding the romantic notions that primitive peoples lived in perfect harmony with the land, taking only what they needed, and causing no harm, evidence suggests that a number of ancient cultures--such as the Anasazi of the American Southwest--were nearly as adept as modern humanity at ecological destruction. Although impossible to prove direct cause and effect, it seems the collapse of a number of cultures took place just after major human-induced ecological changes.

Unless some mysterious spiritual revelation abruptly stopped the sculpturing, it seems the culture that produced the statues of Easter Island came to an untimely end. Perhaps it was a civil war. Maybe a catastrophic eruption from one of island's volcanoes. But John Flenley and Sarah King of the University of Hull in England have another hypothesis. "What we have done is investigate samples of fossilized pollen from crater swamps on the island," Fenley wrote in the British journal Nature. The pollen record is remarkably complete, documenting the existence of over 40 plant species, including giant palms, and offering a detailed look at how the island's vegetation changed.

The oldest pollen dates back some 30,000 years, long before the first people arrived, indicating the island was then heavily forested. Whenever the island was finally settled, its inhabitants began to clear the land for agriculture and livestock. They also cut trees to build canoes, and eventually logs for transporting and erecting the statues. The land was relatively fertile, the sea teemed with fish, and the people flourished. The population rose to about 15,000, and the culture grew sophisticated enough to carve the giant statues.

Regrettably, the trees didn't grow back. "The pollen record shows the deforestation beautifully," says Flenley. "It began about 1200 years ago, and was almost complete by 800 years ago." The islanders also exploited many of the neighborhood's other resources, such as its abundant bird eggs.

The result was ecological disaster. The Easter Islanders had cleared so much of the forest that they were without trees to build canoes for fishing. They also had probably taken so many eggs of the sooty tern that the bird no longer nested on the island. To make matters worse, deforestation caused irreversible soil erosion, destroyed the topsoil, and severely reduced crop yields. Fewer fish, eggs, and crops led to a shortage of food. Hunger, in turn, brought warfare, even cannibalism, and pushed the whole civilization over the brink of collapse. By the time European explorers arrived the population was down to about 600, and the culture that had produced the statues had disappeared entirely.

For Professor Flenley the moral could not be clearer: "Easter Island is the world in miniature. What happened there is what we are doing now to our rain forests and our other renewable resources."