Robbie Knievel loves wreaking his own brand of adventurous havoc. He loves whiskey. He loves a good firm drink to compose his nerves before and after a death-flouting feat.

He loves the daily grind of the daredevil and the buzz of stomping in the footsteps of his eminent old man.

But he now values his life and health more than he does booze. Instead of whiskey and soda, he swigs Diet Cokes in the evenings and nips mochas in the morning. The Butte-born risk taker said that he is wholly committed to sobriety following a felony DUI charge April 21, 2015.

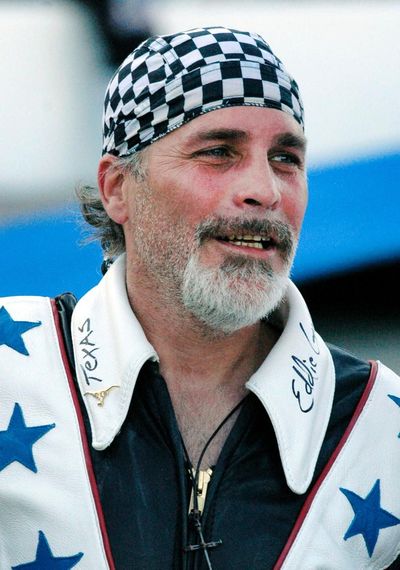

"I am tired of it - the alcohol," said Robbie Knievel, 53. "I have quit. I've learned a lot. And I know there are those who say, 'Well, he'll be back.' Or, 'He's a retread.' But before I was craving a drink and now I'm not. I've been here before, you fight it for 10 days and you get on a roll, but you go back to it. You quit for 30 and get on a roll. But this time, there has not been one single time - not one - since the accident, where I've wanted to go grab a Jack Daniel's bottle. I used to crave it every day. I'm on 90 days of being dead sober on June 22."

Robbie's mind, head and reason must be tightly assembled. He intends to jump over 26 cars -- one more than his 2006 jump in Butte -- on July 25 on East Park Street in Uptown Butte as part of the annual three-day extreme sports festival Evel Knievel Days. In 2011, "Kaptain" Knievel successfully jumped nearly 200 feet, easily clearing 10 passenger vehicles in Palm Springs.

"I haven't jumped this type of distance since Palm Springs," said Robbie. "And I almost broke my back on that jump."

For a man such as Robbie Knievel, if there's not any emotional drive, it's not worth hurling into. Robbie's hook of sobriety is fueling his intense preparation. He has been riding dirt bikes to pump up his forearms, cycling straight up and down, reinforcing his muscles by working the brake with the throttle. He is lifting weights, eating vitamins, and dropping excess weight in his stomach.

"I am trying and practicing harder than I have forever," said Robbie. "This is what I do for a living. So many guys are all balls and no brains. Some guys tried to follow in my dad's footsteps. He was a showman. I'm a showman. I love sparking things up. I'm doing this jump for myself, for Butte, and for my sobriety."

Robbie is using sobriety as motivation, another method of firing up his engine.

"There is a lot of mental stuff to a jump," he said. "The spiritual part I have had for quite a while. But the alcohol, I fought it for years. I quit in the 1990s, 30, 60, 90 days. I did outpatient treatments in the 1990s, and in 1991, I said, I'm an alcoholic. I was sick and my arteries were clogged. I got on these really potent vitamins and my arteries were not clogged anymore. So I started drinking more."

Robbie concedes that, not surprisingly, it was damn difficult being thrust into the silhouette of the world's quintessential daredevil performer and trying to perpetuate his legacy. Evel Knievel's showmanship, flair and disdain for death were so admired that he became a national folk hero. He died in 2007 at age 69. His health had also been undercut by years of heavy drinking; he told reporters that at one point he was consuming a half a fifth of whiskey a day, rinsed down with beer chasers.

Robbie embraced the same traps of that persona.

"I guess alcohol goes with the job (of being a daredevil)," said Robbie. "I was the excuse for the party. Just being a celebrity and a people person and all. But when you can't even hold on to a cup and you are primed for a seizure and a heart attack, it's scary. There are people who have known me since I was young, and they tell, "Hey, Robbie, you look 10 years younger now.' I was tired of hanging around at 53 at the bars. I was tired of the guys who were hanging on my coattails, who also hung around on my dad's coattails."

All Robbie ever really wanted to do was soar the through the air. He learned early that his dad was a daredevil, a performer, a marketing genius. He knew his old man loved the thrill, the money, the whole macho mania. All those things made him one hell of a brand.

"I remember when I was 8 years-old and I was doing a show in Madison Square Garden," said Robbie. "I was on a bike that was way bigger than me and I rode around. Think about it: My dad's jump was the number one rated show in Wide World of Sports history. It doesn't matter if you are Joe Frazier's kids, Elvis' daughter, Muhammad Ali's daughter, whoever, you cannot fill those shoes. Butte was a town of 55,000, and it had a lot of bars. I grew up drinking and with a few bar fights. In Butte, your dad wanted to take you to the bars. I quit high school. I knew what I wanted to do for a living."

Dad wasn't perfect. Evel liked to brag about his early callings as a safe cracker, bank robber, swindler and pickpocket. In 1977, he roughed up his former promoter Shelly Saltman with an aluminum baseball bat after Saltman wrote a negative book, claiming Knievel abused his wife and children, and was a heavy drug user. Knievel was jailed for six months. Regardless of his foibles, Evel was groundbreaking, meaningful, and, at times, enthrallingly eye-opening.

"I remember watching my dad's flapjack race and seeing him at the Moses Lake speedway," said Robbie. "My homework would pile up. We went from a trailer to all these acres and horses and a Ferrari at age 12. I don't think I realized how famous he was until the Snake River Canyon jump. He was a self-promoter. After his toys came out, he outsold GI Joe one year. We would fly to Florida and I would be sanding his yachts at 15. I'd hang out on the speedboat and yachts, and I moved out at 16 - like an idiot."

Before he was ten, Robbie was charging tourists 50 cents to watch him hurdle 10 10-speeds on his mini-bike. Robbie embarked on his own course of rousing performances. He is an old-school jumper. He doesn't practice with a foam pit or a safety net in the backyard. He learned through the onerous debt of birthright, of being ballsy, and just going for it. He uses lower ramps and hits them with the highest of speeds. He once mistimed and landed the middle of the bike so hard that it bounced him over the handlebars. He badly sprained his back. But he did the very same jump the next night - a successful, certifiable no-hander.

He has faced more pressure, tension and stress in the unwinding seconds of the final commercial before a live television jump than most people experience in a lifetime. He has overtaken barreling steam locomotives and sailed over the buildings.

"I've done about 7 or 8 live shows," said Robbie. "That's pressure. Timing and pressure. If you land short you get killed. You could shift wrong one time or miss that gear going to ramp with so much momentum. You can't hesitate. You've got to have the guts to pull the trigger. I have never chickened out. Where would I be? Who wants to be bounced off the pavement at 80, 90 miles an hour? When you clear it nice and clean, it feels good. But if the bike cuts out or seizes before you leave, you are screwed, and you are dead. On this coming jump - any jump - if I hit the front of that ramp wrong I'm done."

True to daredevil form, he has made the element of facing down danger look effortless. In 1989, at age 26, Robbie successfully executed the motorcycle stunt that nearly killed his father 22 years earlier. Robbie cleared the towering water fountain in the parking lot outside Caesars Palace. Robbie roared his 500 Honda up a ramp, soared 150 feet across the fountain, landed on another ramp, and growled safely into an underground garage.

"Sometimes I get butterflies," he said. "Sometimes I get cockroaches in the stomach. You are either churning really badly or you are not. I've had some tight landings. The dues I've paid to hit head on with those jumps - they don't get it. You have to make it look easy. Last jump, I hesitated like crazy. A lot of guys do practice jumps to get the feel of the jump. Practice? It takes away from the real thing. My lower back hurts when I get out of bed every day. Legs, back, shoulders, they are sore. Everything I've injured, it still hits me know. It all started hitting me 3, 4 years ago. Knee surgery. Ankle injuries, torn ligaments in the knee. There are times when you try to get up the next day to go to the bathroom and you have to have someone help you."

It's understandable how alcohol became a close confidante in such a psychologically dramatic lifestyle.

"I've done ton of jumps sober," said Robbie. "I did like to take a shot to calm the nerves. One shot was not going to make me drunk. Your adrenaline is high. After a jump, you and your friends pile into a bus or a motor home and have a few strong Jack and Cokes. Hey, you just risked your life. There is a huge adrenaline on both ends. It takes a couple of days to settle down. The drinking went with it, just like any entertainer. But you don't just go out there and sing. There is no backing out. I risk my neck. I could back out. I don't see it happening anytime soon."

Hopefully, the tipping point of Robbie's redemption narrative happened last April in Butte. He rear-ended another vehicle, busting his lip in the crash. He fled the scene and was subsequently apprehended on foot. He refused to take a Breathalyzer and was charged with felony DUI and three misdemeanors. He has prior DUI convictions.

"My friend let me use their car and I was drunk and tired," he explained. "I remember the last stoplight and I woke up in the back of the police car. My mouth must have bounced off the steering wheel. The transmission to the car was drained. I was thinking, 'What am I doing?' The car ran out of transmission fluid. Cops were there. I got out and I said, I'm guilty." Nobody got hurt. But it sure woke me up."

Robbie 's next step is anybody's guess, including his own. He returned to Butte in 1990s after the successful Caesar's Palace jump and worked hauling logs at a sawmill. Six months later, he was gone. He recently lived in Las Vegas. In the week leading to Evel Knievel Days, he felt confident enough in his sobriety to sit in the bars of his youth and drink Diet Cokes. He stayed 10 or 15 minutes in one bar, swapped a few stories and greetings, and then he moved on to another.

"I like to hide out these days and I skip the parties," said Robbie. "I've got my whole life in front of me. I feel like I'm just getting started. I feel like Keith Richards or something, smoking and jumping motorcycles."

Tempered by years of hard experience, Robbie would like to go back on the road. He still plans to transcend stunt jumping, transcend sport, and transcend the parameters of civilization, of life and death. Provided that paramedics and surgeons will not have to splice him back together this weekend, he will jump elsewhere. He may live in his tour bus, making the rounds signing autographs.

"I am still going to be jumping," said Robbie. "I've had major knee surgery, lower back issues, lumber issues, concussions, I don't know how many of them. I've had 24, 25 broken bones. But I never broke as many bones as my dad did (purportedly 433, according to his obituary). I like to say that I am the son of the greatest daredevil in the world."

Perhaps Robbie should reject the notion that he has to gain in magnitude until he appears larger than life. He is a top-notch showman. He is his own legend, the accomplished heir who dignifiedly buffed the crown of a daredevil dynasty. But he belongs to legacy, to adventure, to the sentiments of his old man, who once commented that, "Sure, I was scared. But I beat the hell out of death."

"I'm happy," said Robbie. "I believe it may take one full year to get back into the limelight. But I am going to keep the name going as long as I can. It's the most famous name on two wheels."

Brian D'Ambrosio's latest book, "Life in the Trenches," earned an independent book award for non-fiction. It offers 37 narratives and stories of modern day trench warriors - including Stephen King's favorite folksinger (James McMurtry); a Greco-Roman wrestler and MMA forefather from the Midwest (Dan "The Beast" Severn); entertainment wrestlers so convincing as villains that they repeatedly put their own lives in danger (Ivan Koloff, "Rowdy" Roddy Piper).