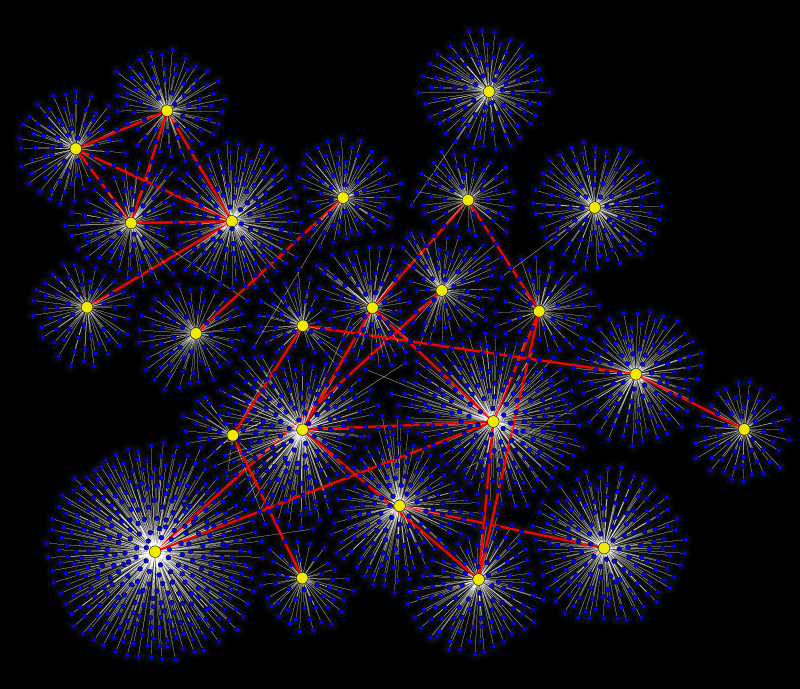

This shows networks created by phone calls (blue) made by participants in the study (yellow) and the bonds of friendship between the participants (red) in the first half of the investigation period. (Image courtesy of Dr. Jari Saramäki of Aalto University)

In recent years new technologies have entered virtually all aspects of our social lives. Mobile devices such as smartphones and a multitude of messenger apps make us reachable and findable no matter where we are. Online social networks, such as Facebook and LinkedIn, provide new ways of keeping track of large numbers of social contacts and their activities, as well as helping us find old friends. The abundance and pervasiveness of new technological platforms and devices that can mediate social interactions would appear to suggest that we are not only finding new channels for communication, but that our social world is being enlarged and transformed. At the very least, shouldn't we expect that these new technological means improve our ability to support an increasing circle of close friends?

Interestingly, the answer appears to be no. The evidence for this claim is provided by the results of a study that I was involved in, carried out by an international collaboration with researchers from Aalto University in Helsinki, the University of Oxford, and the University of Chester, which has just been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. The study tracks 24 high school students over a period of 18 months, as they make the transition from school to university or work. The observation period for the study is particularly interesting, because it represents a time when social relationships are likely to be in flux, with new friendships forming and some existing friendships becoming less important. In our research we relied on the combination of two quite different methods to try to understand what is happening. First, all participants in the study were provided with free cell phones for which we paid the bills during the 18-month period, and in return they gave us their consent to record the phone number, date, time and duration for each call that they placed. This provided a detailed picture of each participant's communication patterns. Second, all participants completed an extensive survey at the beginning, mid-point, and end of the study. This allowed us to capture who was at the other end of the line when they placed a call (e.g., family member, friend, etc.), and also to account for interactions such as face-to-face meetings which would not show up in our records of phone calls. Most importantly, the survey allowed us to divide the overall 18-month period into three consecutive six-month observation windows, and to compare the recorded phone call activity with self-reported scores for the emotional closeness associated with each relationship. As it turns out, the number of calls placed and the self-reported emotional closeness score were strongly correlated, and this justified our using the call patterns to track changes in the strengths of social relationships.

Social Signature

So what did the detailed data that we collected reveal? This question is best answered in terms of a characteristic that we decided to call the 'social signature' of an individual, and in particular by looking at how this 'social signature' changed over time. Imagine one of our participants during the first six-month observation window. She or he will call some people very frequently, and others only occasionally, where the people called are likely to include relatives, close friends, and more distant acquaintances. If we now rank order the people called by our participant, with the person most frequently called in first position, the second-most frequently called person in second position, and so on, then we can build a profile of how the participant allocated calls between all of their different social relationships. This profile is in fact what we call the 'social signature,' and it reflects what fraction of calls a given participant placed to the person they call most, the fraction of calls the participant placed to the person they call second-most, right down to the least frequently called person. So what was the 'social signature' able to tell us?

First, let me describe a general property that applied to the 'social signatures' of all participants. The number of people that participants called frequently, with whom they had a strong relationship, was comparatively small. A larger number of people were called less frequently, where the corresponding relationship was weaker. In short, we may have five close friends and 20 acquaintances, but we are very unlikely to have 20 close friends and five acquaintances. If we look at the 'social signature' in greater detail, we find that there were variations between different participants, so that one individual may have had three close friends and another seven. That is in fact why we chose the term 'signature,' because we discovered that there is heterogeneity between different individuals.

Perhaps most interestingly, if we looked at the 'social signature' of a given participant over the three consecutive six-month observation windows, we found that it remained quite stable. It is worth taking a moment to reflect why this should be surprising rather than self-evident. The social world of our participants was undergoing a significant transition, with changes in both close and less close friendships. By the end of our study, the identity of some of the close friends of the participants had changed, and so these relationships were now with entirely different individuals. Despite this churn in terms of the actual people involved in the relationships, the pattern of the fraction of the calls participants placed to a counterpart of a given rank-order (i.e., the 'social signature') remained largely unchanged.

How can we understand the persistence of an individual's 'social signature'? The key is that the pattern of our social relationships is shaped by a number of critical constraints.

- Time: The first very general and quite inescapable constraint is that we only have a finite amount of time to maintain social relationships.

These three factors (time, emotional capital, cognitive limitations) may explain why an individual's 'social signature' doesn't change over time. Returning to and rephrasing the question that I started with, can the new social technologies that we have access to significantly change the three factors that we believe shape the patterns of our social interactions? Based on the behavior that we observed for our participants, at this point I would tend to answer no.

Felix Reed-Tsochas is the James Martin Lecturer in Complex Systems at the Saïd Business School, University of Oxford.

Related

Sign up for Peacock to stream NBCU shows.

to stream NBCU shows.