The sun may no longer be considered an only child.

A University of Texas astronomer has identified a star 110 light-years from Earth as a probable "solar sibling." The star likely originated in the same star cluster as the sun, and that could yield fresh insights not only into how our home star was born about 4.5 billion years ago but also into how life on Earth got started.

"We want to know where we were born," the astronomer, Ivan Ramirez, said in a written statement. "If we can figure out in what part of the galaxy the sun formed, we can constrain conditions on the early solar system. That could help us understand why we are here."

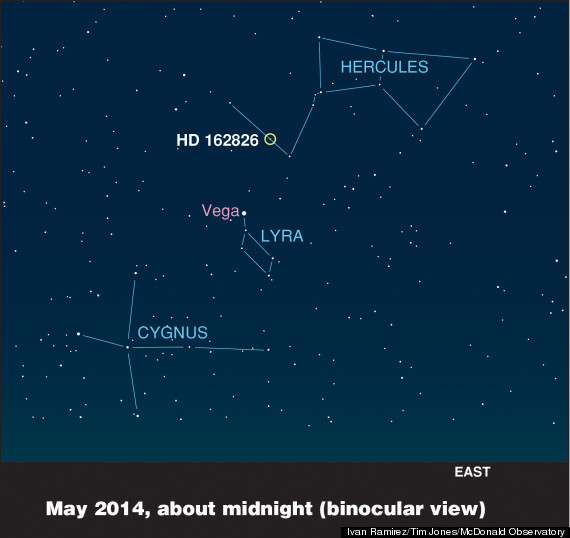

Star HD 162826 is located in the lower leg of the constellation Hercules. Though not visible to the naked eye, the star -- which is 15 percent more massive than the sun -- can be seen with binoculars. Skywatchers can look toward the star Vega to spot the sun's sibling star.

(Story continues below.)

University of Texas at Austin astronomer Ivan Ramirez identified star HD 162826 as a probable "solar sibling." (Ivan Ramirez/Tim Jones/McDonald Observatory)

To find HD 162826, Ramirez and his team studied 30 stars that other astronomers had identified as potential solar siblings. Using the Harlan J. Smith Telescope at the McDonald Observatory in Fort Davis, Texas, and coordinating with researchers at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, Ramirez narrowed the list by analyzing the orbit and chemical makeup of each star. Under the research, HD 162826 was the only star in the group that satisfied the team's "dynamical and chemical criteria for being a true sibling of the Sun."

Evidence suggests sibling stars may host Earth-like exoplanets that might be capable of supporting life -- so by investigating the origins of the sun, researchers may also be advancing the search for extraterrestrial life.

"The idea is if a planet has life, like Earth, and if you hit it with an asteroid, it will create debris, some of which will escape into space," astronomer Mauri Valtonen of the University of Turku in Finland told Space.com in 2012. "And if the debris is big enough, like 1 meter across, it can shield life inside from radiation, and that life can survive inside for millions of years until that debris lands somewhere. If it happens to land on a planet with suitable conditions, life can start there."

Ramirez's findings are slated for publication in the June 1 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.