Dana Catoe is a Class One Police Officer with the Lexington County Sheriffs Department in Lexington, South Carolina. He rides with the Blue Irons, a policeman's motorcycle group. He frequently lectures around South Carolina about his experiences in Iraq and in the Marines.

By Dana Catoe

The debate about whether the Confederate Flag should be taken down is raging throughout the nation. Pictured in this photo are flags at the Pointe au Chien Indian Tribe Community, Louisiana. Photo courtesy of Richard May. Visit his website.http://www.azoeart.com

I clearly remember how racist terms used to describe Muslims like rag heads and sand scratchers, embedded in me through my South Carolinian upbringing and military training, finally lost their meaning.

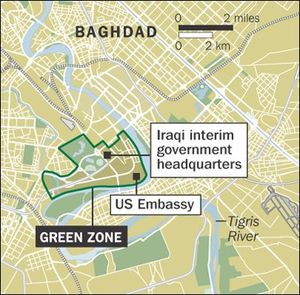

I was 39-years old. I'd retired from the military after two decades and landed a private contract job heading security for the Iraqi Interim Governing Council, Central Headquarters in the Green Zone in Baghdad. It was the first time in my adult life I wasn't insulated from other ethnic groups by fellow Marines or US society.

Returning to my American and Christian roots to comprehend horrific circumstances provided me with compassion for people I'd been taught to detest.

Race-based violence, such as the mass murder committed by Dylann Roof, may be prevented by weeding the roots of our prejudices. First, we must admit they're there. Racism is ever-present when I respond to violent scenes as a South Carolina police officer--whether the perpetrator is white or black. Personally, I've heard (and occasionally echoed) ugly words describing different groups growing up. I transferred these hateful sentiments from my African American neighbors to "the enemy" in multiple countries during my Marine service. I certainly wasn't the only one.

Exposure

Iraq was a good teacher. I arrived in late 2003 as the only American on the compound. I was in charge of securing the safety of an entire government including: Shiites, Sunnis, Kurds, a Turk and a Syrian Christian; 300 Nepalese Gurkha fighters and 2500 weekly visitors.

My experience with strategic defense secured me the position, but I didn't understand Muslims. Serving in Afghanistan taught me to distrust, if not downright hate them. We either ascribed or perceived negative foreign qualities in Muslims. We probably didn't know exactly why.

Courage

One major perspective shift occurred on January 30, 2005 when Iraq held its first free elections in 50 years for a transitional National Assembly. I am a red blooded American. I proudly served in the Marines to defend the freedom of my daughter and neighbors, of Americans and the American flag. I'm privileged to have been born here, and never take that privilege for granted.

I knew the American notion of democracy couldn't be adapted in Iraq overnight---due to thousands of years of culture, history and tradition. However, my Iraqi colleagues were hopeful about securing more autonomy over their government and their lives.

I stood on the compound at 9 a.m., disappointed, because the streets I was looking down upon were desolate. Around 10:30, people started trickling out. By noon, the streets were packed. Iraqi families walked bravely, despite insurgent threats that anyone who voted or had ink on their finger indicating they'd voted would be killed. Many voters had relatives who'd been raped, imprisoned, slaughtered. Still, over 8 million people turned out.

Watching people risking their lives to vote humbled me. I felt proud for the Iraqi people. Admittedly, I was also slightly ashamed for my own country. I thought back to nearly empty voting facilities in South Carolina where we were free. I believed US citizens would stay locked behind doors if there was a chance we'd be killed for voting. I gained an immense respect for Iraqi people that day.

Some things were harder to fathom.

Inshallah

A 2100 pound car bomb exploded at the gate I guarded. The car careened around the corner. Debris was strewn everywhere. People ran in slow motion. On autopilot, I pulled Concertina wire across the road to keep other cars out.

I finally walked towards the stopped car and picked up the distinct, unnatural scent of burned flesh. I stood, and looked through the blown window. A nine year old boy was still strapped in the seat, bleeding from his nose and ears. He wouldn't survive.

I'd seen a lot of violence in the military. I just couldn't wrap my mind around terrible things happening to children. Seeing that boy changed me in a way I'll never be able to put into words.

"Inshallah," my translator Sa'if later said when I told him about the boy. "It is God's will."

I'd heard that phrase often, in Iraq. It seemed to be repeated whenever somebody wanted to excuse terrible things that happened as being predestined, that couldn't have been prevented. I thought about the elections, how people fought for change. Inshallah seemed counter intuitive to everything I believed.

"No. It's not Inshallah. It's not Gods will. That boy didn't have to die" I yelled.

Sa'if looked at me sadly, as if he pitied my status as a naïve American, as if my outburst confirmed his belief his reality was something I'd never be able to truly understand.

Later, I started to understand a bit more.

Faith

When the Green Zone was attacked multiple times over a period of 24 hours, a rocket destroyed my house, so I went to live at the Al Rasheed Hotel. My room was on street level because the floors above were destroyed.

When I'd first arrived in Iraq, the sound of mortars raining down sent waves of fear throughout my body. For months after the attack, I lay on my bed with the window open, falling asleep to the sound of those mortars popping. I'd gotten used to almost everything. Yet, one night, for some reason, I lay there haunted by the memory of the boy from the car bomb. I couldn't shake it.

I didn't think about the boy's destroyed face, but his history. At 9-years-old he'd only known violence. His parents couldn't protect him. They just couldn't. Children shouldn't have to live that way, especially not for the reasons we were claiming the war was important.

I grappled with the memory a long time. Later, I lay there, and an odd warmth flooded my body. It was vaguely reminiscent of the feeling I got as a child praying at the Second Baptist Church in South Carolina.

The sensation was so unexpected, and familiar. Despite everything I had witnessed, or perhaps because of it, I still had faith. This realization brought me an incredible feeling of relief, so poignant I almost broke down. I again trusted there's deeper spiritual meaning to our lives.

Understanding

Laying in the hot hotel room, grappling with what happened to that boy; also filled me with compassion, a kind of human solidarity, with what the Iraqis were going through.

In this context, I thought again about the word Inshallah. I considered whether people who suffered weren't necessarily dismissing the horror their children endured as pre-destiny, but using it as a prayer and a reminder of their own faith. In that way, they were no different than me.

I won't say all my preconceived notions about Iraqi's vanished during the years I was out there. They didn't. Still, I met some good people I respected. I made great friends. I understood more.

There is no magic formula to annihilate racism. Acknowledging we may have regurgitated hateful, flimsy terms that don't necessarily reflect what's in our true hearts is a start. The only real way to really get rid of prejudices is to become more familiar with each other; and to witness, as I did, how through our suffering and vulnerability we're all pretty much the same.