This article is a part of Faith Shift, a Huffington Post series on how changes in demographics, culture, politics and theology are transforming religion in America.

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. -- On a recent Tuesday night at Rojos, a trendy Mexican restaurant on the south side of the city, a group of women were kicking off an unusual welcome party for someone they'd never met.

Their guest of honor: Lisa Pataky, a 25-year-old student who was new to town, trying out a summer internship and considering moving to Birmingham full-time. Around her were supporters of the Birmingham Jewish Federation, peppering her with reasons to stay: abundant jobs, lack of traffic, low cost-of-living, and -- most important -- a friendly, tight-knit community of 5,200 Jews spread among five congregations.

Caren Seligman, the outreach coordinator for the group, had recently been introduced to Pataky through a mutual friend. And Seligman was the one responsible for inviting these women to the restaurant that evening for their first crack at recruiting Pataky to their city.

"If I can get her to like this place for the next six weeks, maybe I can get her to move back here when she graduates," Seligman, 53, recalls thinking at the time.

Though the population of Jews in the South hovers at 1.1 million overall, Jewish life in less bustling parts of the region has taken a dive. More than half of Southern Jews -- 638,000 -- are in Florida. Another 140,000 are in Texas; 120,000 reside in Atlanta, and 97,000 are in Virginia. But the Jewish communities in cities like Birmingham have suffered.

"There has been a huge influx of Jews from the Northeast down South," says Stuart Rockoff, director of the history department at the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life in Jackson, Miss. "But there's also been a significant migration of Jews from other parts of the South to big Southern cities."

Alabama, once a beacon for Jewish immigrants and American-Jewish migrants seeking prosperity in its booming steel industry, has 8,850 Jews left in a state of 4.8 million people, down from a high of 13,000 in the early 20th century, when the state's population was less than half of what it is now. The decline has become more evident as historic congregations and communities have lately shut their doors and withered.

In the small towns surrounding Birmingham, two synagogues have closed in recent years and two Jewish religious schools have merged. Synagogues in a handful of other Alabama towns -- the state's 16 amount to a third less than what it had at its peak in 1927 -- are in danger of closing. Several don't have rabbis and are led by volunteers. In Greater Birmingham -- home to one million Alabamians and the bulk of the state's Jews -- the Jewish population has plateaued, and by some estimates, declined. Meanwhile, the region's broader population has grown by tens of thousands in a decade, fueled by growth in its medical research industry.

To help combat this trend, Seligman, the outreach coordinator, is looking for a few good Jews to bring to her city.

The stakes are high. Not only could Birmingham's historic synagogues one day disappear, but so could its secular Jewish organizations, including popular schools and social service groups that often cater to non-Jews. For Seligman, who lost her own children to the Jewish metropolises of Houston and Minneapolis but dreams of the day they move back, the job can get personal.

Her task is not easy. She works long hours -- often arriving at her modest office by sunrise -- trying to recruit young Jews, one at time, to a city with a graying Jewish community that's eager for a more balanced population. She tracks down college students who have moved away to entice them to return. She travels to campuses as close as Tuscaloosa, Ala., and as far as Bloomington, Ind., to pitch the city to students who would otherwise end up in Chicago or New York. She fields phone calls from strangers considering jobs in Alabama. When a new Jew arrives, she's ready with a welcome kit of shabbat candles, kosher wine, memberships to the Jewish community center and a pitch to stay.

Once a place where Eastern European Jews flocked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Birmingham was home to powerful, enterprising Jews who ran major merchants and department stores, such as the now-defunct Parisians chain. Poised for much of its history to become the new Southern Jewish metropolis -- the titles instead went to Atlanta and South Florida -- the community is now at a crossroads.

The old are getting older. The young are in short supply and headed to big cities. Neither the smaller towns that once fed into the city's Jewish landscape nor the region's former industrial or retail strength can be counted on to propel the population into the 21st century.

Birmingham isn't the only place recruiting Jews. In Tulsa, Okla., a similar effort is underway, while in Dothan, Ala., and Meridian, Miss., graying small-town synagogues have offered to pay Jewish families as much as $50,000 to relocate. In New Orleans, where Hurricane Katrina wiped out an Orthodox synagogue, the Jewish federation gives small stipends and memberships to a Jewish dating website to encourage newcomers to settle.

Fueled by immigration and transplants from other parts of the country, the religious makeup of the South has diversified, with Islamic, Mormon and Spanish-speaking congregations making headway in places once reliably spiritually homogeneous. Birmingham, too, has become more diverse. But unlike more prosperous Southern cities with large Jewish populations, Birmingham's Jewish community is being confronted with a harsh reality: it needs to grow to survive.

"We're not worried about the Jewish community in the next ten or 20 years," Seligman says. "We're worried about the next 100."

* * * * *

A third-generation Sephardic Jew, Seligman exudes Southern hospitality with a sense of cosmopolitanism that sets Birmingham apart from much of the state. She punctuates conversation with "sweeties" and "honeys" while extending her vowels in a drawl. She has a weakness for iced tea and banana pudding, and can only take the "hustle and bustle" of big cities like Atlanta for a few days at a time.

With seemingly endless energy, she starts her workday by checking emails and text messages from home before arriving to the office hours ahead of her small group of colleagues. A recently certified spin instructor, Seligman leaves mid-morning to teach class, an occasion where small-talk after exercises often leads her to learn about new Jewish arrivals to the city. In her rare moments of relaxation, she enjoys lounging on the white coastal sands of the Florida Panhandle. When she picks up newcomers for tours of the city, she opts to use her top-down convertible over her sedan, where her stereo shuffles between Frankie Valli, Michael Jackson and Maroon 5.

But when she imagines what her Jewish community may look like in a generation, she thinks back to growing up in Montgomery, 90 miles south of her current home.

She remembers the festive songs and celebrations at Congregation Etz Ahayem, the Sephardic synagogue her grandparents' generation helped establish in the early 20th century after immigrating from Rhoades, Greece. The small temple -- its name means "Tree of Life" -- would overflow on Fridays with the close-knit 30 families who had maintained it for decades. Prayers were in a mix of Hebrew, English, and Ladino, a flavorful Judaeo-Spanish tongue.

Like many of those she tries to lure back into the city, Seligman moved away from her birthplace after college in Tuscaloosa to follow her career in advertising and her Birmingham-raised husband. Her son's bar mitzvah and confirmation were at Birmingham's Conservative temple (their original rabbi moved to a new job in Atlanta three years ago) and she became an active volunteer in the community.

But each year for the High Holidays, Seligman would return to Montgomery for services at the temple of her forefathers. Cousins and old neighbors would catch up over fried snapper and potato and cheese-filled pastries, traditional Sephardic foods that transported Seligman back to her childhood.

Etz Ahayem, no longer able to sustain a congregation and long without a full-time rabbi, closed and merged with another synagogue a decade ago. Its Torah scroll was transferred to the new temple along with its sanctuary doors. The building is now a Baptist church, indistinguishable from so many others. Only a memory remains.

Seligman hopes the same won't prove true for Birmingham's Jewish communities.

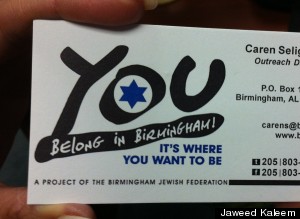

In her purse, she carries black-and-white business cards stamped with large blue Stars of David. She'll slip them into the pocket of any young Jew she comes across. "YOU Belong in Birmingham!" they say in large letters beside her phone number.

Like most of the broader American-Jewish community, most Jews Seligman recruits are secular or from the Reform or Conservative traditions. Her own spiritual observance is varied. She attends synagogue once or twice a month and hosts shabbat dinners on Fridays. She also enjoys the occasional barbecue pork rib.

She's armed with the email addresses of hundreds of young Jews who have left Birmingham -- procured from their parents -- a stack of resumes and an inbox with descriptions of job openings. Her goal: to get one child from every Jewish Birmingham family to settle in the city and to convince those who happen to pass through that it's a worthwhile place to be Jewish.

That can be difficult.

* * * * *

Pataky, the student who arrived in Birmingham in the spring for an internship as a physical therapist, knows the hurdles.

"When I moved here, it was Passover. And when I said to people around town that I was observing Passover, nobody knew what it was," she recalls. "I never had to explain it before."

Jefferson County, where Birmingham is located, is commonly ranked as one of the most Christian places in the nation -- there are 67 churches for every synagogue. But despite the community being overwhelmingly Christian, its people by and large embrace diversity. There are two Hindu temples, two Buddhist temples, a Sikh gurdwara and several mosques. Birmingham is also home to a small community of Russians and popular Greek and Lebanese restaurants.

No matter for Pataky. A self-described "atheist cultural Jew" who observes the occasional Jewish holiday, she has a month to go in the city. It's not a bad place, she insists. She's not accustomed to being around so many evangelical Christians, but everyone has respected her beliefs. She's grown attached to the craft brewery not far from her suburban apartment. She loves the job and has been less bored since making friends through Seligman's introductions over sangria.

But when her internship is done, she hopes to move to New York, Boston, Atlanta or Washington, D.C. All have sizeable Jewish populations. She doesn't want to join a synagogue, but she does want to be around people who understand her.

"There are some natural cultural differences between Jewish people and others. It's nice to have a certain baseline with people you meet," Pataky says. "If I move to New York, I'd probably never even have to think of being Jewish." She feels the same about Atlanta.

While she isn't looking for a religious community, Pataky's social needs echo a refrain that Seligman often hears. Young people want to be around people like them. They want variety and a big singles scene. They want a city with a major sports team. They want to be by the buzz. Birmingham, which is revitalizing its downtown with lofts, art galleries and a burgeoning restaurant scene, still pales in comparison to bigger cities.

"All these kids go to Atlanta thinking this is going to be the place. This is where I'm going to meet that person or land this perfect job, you know, because it's Atlanta," Seligman says. "I tell people when they call me and say they are thinking of moving to the South, 'We are no Atlanta and we don't want to be.'"

Birminghamians are proud of their city, which is situated in a valley surrounded by lush, parallel mountain ranges and majestic hillside homes. Blacks and Jews here played a pivotal role in the civil rights movement. While the city of Birmingham has one of the highest crime rates in the nation, the metropolitan area has one of the lowest. Anti-Semitism is rare, though there have been isolated incidents.

About 80 percent of Birmingham Jews are members of a synagogue or otherwise involved in Jewish organizations, according to the Birmingham Jewish Federation, making for a close community of familiar faces. Nationally, the Jewish affiliation rate is 51 percent.

Despite its selling points, there's a certain unease among some Birminghamians about their city. Though its neighbor two-and-a-half hours east was also founded as a railroad town in the mid-19th century, the growth spurt that hit Atlanta never transferred to Birmingham. Many Birminghamians will lament the conservative Christian culture that pervades everyday life outside the area's urban core, where more than a third of Alabama's counties ban alcohol sales. They'll half-jokingly call the city, where a 24-hour restaurant is rare, "Boringham."

* * * * *

"Our growth really depends on the fortunes of the city of Birmingham," says Rabbi Jonathan Miller, a Reform rabbi who has led the city's largest and oldest Jewish congregation, Temple Emanu-El, for 21 years.

He points to the University of Alabama at Birmingham, home to one of the best medical research programs in country, which has attracted an increasing number of the region's new Jews and temple members.

He mentions the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa -- about an hour from Birmingham and a feeder to the city -- where a vigorous campaign to recruit Jewish students recently resulted in a 50 percent increase in Jewish enrollment over just a few years. Similar to Seligman's program, the university's efforts included visits from admissions officials to far-flung Jewish communities in Maryland, Texas and Georgia. A new Hillel building opened in 2010 that serves 675 students, and the Jewish fraternity and sorority have grown.

The Birmingham Jewish Federation's recruiting, which began six years ago, has so far netted a few dozen new or returning young Jews to the city, and Miller has gleefully offered a spiritual home to many of them.

His congregation, which dates to 1882, has about 690 members, according to Miller. About a quarter of them attend services in its airy, 62,000-square foot temple that includes a sanctuary with colorful stained glass windows, small chapel, religious school and banquet hall. While Miller boasts that membership has barely budged during his time, he admits it’s graying.

Last year, Miller hired a 27-year-old rabbi to increase young adult involvement in the temple. Rabbi Laila Haas, who was raised in Miami Beach and studied in Cincinnati, has started discussion groups at members' homes on religious and cultural topics, including lessons, she says, "on how to express myself Jewishly in a non-Jewish place." While synagogue memberships can typically cost thousands of dollars, Haas says she encourages young people to join by asking them to both pay and get involved "at their comfort level."

For the more traditionally religious Jews, Birmingham has been a harder sell, but improvements to religious life have been made in recent years. The region's first kosher restaurant opened a year ago, and the Modern Orthodox synagogue has hired an energetic 30-year-old rabbi to reinvigorate its small congregation.

Still, a mohel, a rabbi trained in performing ritual circumcisions on newborns -- a segment of the population the city needs if it is to grow -- is harder to find.

Some Birminghamians have a physician do the medical procedure while a local rabbi says prayers. But for the group of mostly young couples and less traditionally religious Jews that regularly seeks a mohel's services, the most popular choice is farther away.

He's in Atlanta.