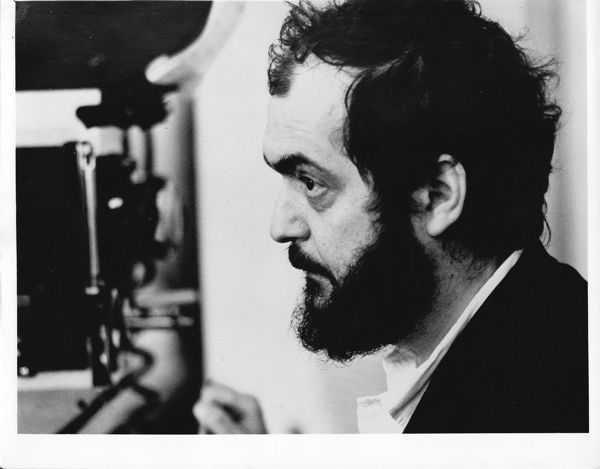

Stanley Kubrick believed that "filmmaking is an exercise in problem solving." He meant that to include the distribution and marketing of his films as well as their production, and he devoted more time and effort to managing the release of his films than any other director. In my view, it's one of the reasons he made only 13 films in 46 years. He relished the problem-solving.

I spent two years overseeing the marketing of Kubrick's 1968 masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey, devising its successful 70-mm. relaunch strategy, before joining him in England to handle the release of A Clockwork Orange. Our collaboration began shortly after Clockwork wrapped and lasted through its December 1971 premiere, its official U.S. release date of February 2, 1972, and throughout its extended rollout. With Stanley's rare combination of meticulousness and creativity, we achieved what we set out to accomplish -- but the most influential result of our collaboration was unexpected.

The distribution of A Clockwork Orange was profoundly influenced by the unique marketing history of its predecessor. 2001 was MGM's most expensive film to date. The fate of the company, which was in the midst of a proxy battle, depended on its success. It was greeted with derisive, negative reviews by the mainstream press and public -- unprepared for its radical, non-linear style -- until alternative audiences embraced it as a cinematic breakthrough.

Three and a half years later, the "X"-rated A Clockwork Orange opened to rave reviews in the United States, in a perfectly choreographed advertising-publicity-exhibition campaign that broke house records in every major city. Unlike the first, misconceived 2001 campaign, nothing was left to chance, including the crucial selection of cinemas, which were usually decided by a studio's sales executives.

2001 was a special roadshow film, meaning it was presented with higher prices, reserved seating, and usually 10 performances a week. Only one to three roadshow cinemas existed per city and were easily identified.

Clockwork would be shown in standard cinemas as a quality platform release, which meant there were many options per city. I knew that Don Rugoff's Cinema 1, the most prestigious cinema in New York, had to be the New York theater, but how to be sure that the film would be booked into the best cinema in Indianapolis or Cleveland or Atlanta? To choose the right theater in each city, we needed to know which cinema sold the most tickets to the most interesting pictures. But while a studio would know what its own films grossed, detailed box-office figures of competitive films were closely held secrets. There was no comparative information, and that is exactly what Stanley wanted.

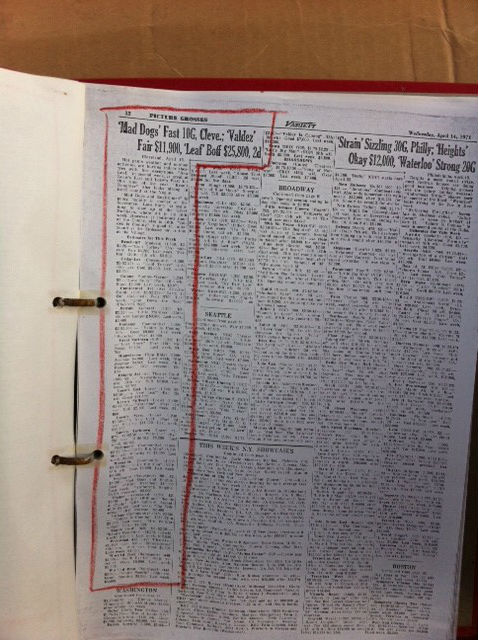

Brainstorming the problem with Stanley at his home office in the countryside town of Borehamwood, England, I pointed out that Variety published a weekly breakdown of cinema grosses for first-run releases in most major markets. These differed from the cumulative box office chart in several important ways: they specified the weekly gross per theatre and previous week's figure from whatever film had played, plus seating capacity and ticket prices. Lightning struck as Stanley examined the trade magazine more closely. We could chart the gross of every cinema in every city over time by building a spread sheet -- if only we could find a substantial number of back issues.

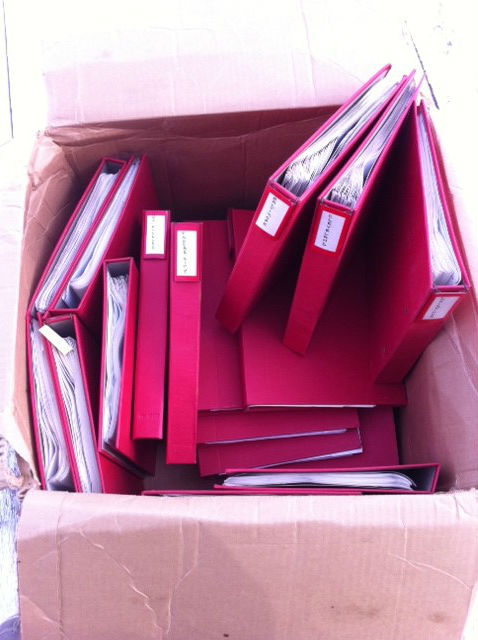

Variety's London headquarters held copies for 18 months, which were soon in my office, in the guest house of The Chantry, the estate next to Abbott's Mead, where Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton reportedly stayed while making The V.I.Ps at MGM Elstree down the road.

And so, for the next six weeks, Maureen, a sweet lady from St. Albans, entered the figures from The Music Box in Chicago and The Orson Welles in Boston and the Bijou in St. Louis and a thousand additional American cinemas onto individual pages of accounting paper, which were then compiled into looseleaf notebooks, alphabetically listed by city and subdivided by cinema. This hand-crafted data base would be our bible, guiding our directives to Warner Bros. concerning which cinemas should show A Clockwork Orange.

Leo Greenfield was Warners' vice-president of distribution, with a Borscht Belt delivery reminiscent of Henny Youngman. When he called to discuss the theater selection, we'd have the notebooks at our fingertips. As Leo would go through his choices, I'd be next to Stanley, pointing out a better alternative if necessary.

"Well, what about The Ritz in Philadelphia, Leo?" Stanley would say. "Midnight Cowboy ran for six months and ended its run at $10,000 in its last week? Nothing looks better than that."

"And in Columbus, The Wild Bunch had a great engagement at The Paramount, which is perfect for our audience."

The calls would go on for nearly an hour as Stanley, knowing Leo was dumbfounded at the other end of the speakerphone, moved around the office with a wry smile on his face, hitching up his pants and winking at me as Leo, already in awe of Stanley's reputation for thoroughness, promised to get back quickly after he checked out the preferred cinemas and their availability. It was classic Kubrick, winning the chess match through perseverance and ingenuity.

Word quickly spread that Stanley had a computerized system to track theaters and grosses based on technical information he had acquired while developing HAL 9000, the all-knowing computer in 2001. For months these stories persisted in the trades as the roster of Clockwork cinemas was refined. They were neither confirmed nor denied.

In March 1972, after the first 25 Clockwork engagements had established new house records, I was in my Burbank office at Warner Bros. when Stanley called, sounding serious.

"Mike, I just got a call from Abel Green."

Abel Green was the legendary editor of Variety and the most respected and important figure in the trade press.

"What did he want?," I asked, nervously.

"He asked about the computer system because he wants to adapt it for Variety." Trade stories of Stanley hoodwinking the studio raced through my mind.

"What did you say?," I replied, already planning damage control.

His tone changed; there was a twinkle in his voice. "I told him how we had done it, how necessary the information was for the business and what computers could do the job. He was very appreciative."

Stanley was in top form.

Over the years, Variety instituted various changes in the configuration of its weekly box office list. The listing of roadshow screens was eliminated as the industry discovered via Jaws, the fiscal advantage of wide release booking with saturation TV buys. Subsequently, both weekend and full week totals were shown, along with the important weekly percentage change, which we had originally charted in our hand-crafted theater by theater data base.

As these general statistics became easy to digest and the release patterns generated higher dollars, the consumer press began citing box office winners as part of their general reporting. Today, the business of the movie business is common knowledge with weekend

openings given like Dow Jones numbers.

I trace it back to Stanley's need to know and think of sweet Maureen, sitting at that long table in my office, carefully going through Variety, transcribing those grosses into ledgers, and wonder if she ever realized what her efforts -- at $65 a week -- have wrought.

This post has been modified from its original publication.

An earlier version of this post contained three inaccuracies: 2001 was released in 1968, not 1969, and the all-knowing computer was named HAL 9000, not HAL 2000.