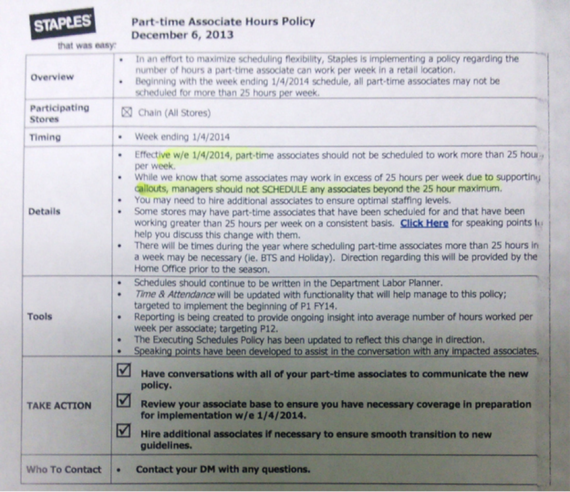

On February 9, Buzzfeed reported that Staples, the large office supply chain, had stepped up its enforcement of a cap on hours worked for part-time employees. Despite the company's unconvincing claim* that the policy is longstanding, it appears that Staples implemented the 25-hour-per-week cap in January of 2014 "to skirt impending rules requiring companies to provide health insurance" to employees who work at least 30 hours a week.

Staples' decision will undoubtedly renew arguments that the Affordable Care Act's (ACA's) employer mandate -- the provision that requires companies with more than 50 full-time workers to insure employees who work at least 30 hours each week -- has led to harmful effects on work. These arguments, like parallel narratives about minimum wage laws and paid sick leave ordinances, are largely inaccurate, and advocates of evidence-based, power-balancing policy are absolutely right to debunk them.

However, we cede too much when, as is often the case, we default to a defensive stance. "Yes, the negative incentive is there, but the data show such effects to be small or non-existent" should not be the full scope of our response.

Instead, it's imperative that we change the nature of these conversations. As Thomas Pynchon astutely observed: "If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don't have to worry about answers."

Opponents of an employer mandate, minimum wage, and paid sick leave want people to focus on what employers will do in response to each policy's enactment. The more relevant question, however, is about what employers can do.

First, it's important to remember that businesses can deduct employer-provided benefits from their tax bills, and that the employer contribution to health benefits is widely viewed as coming out of worker salaries. Providing employees with health coverage, decent wages, and paid sick leave costs less money than a lot of people think, though it's certainly more expensive than offering meager wages and no benefits.

More importantly, providing such benefits is the right thing to do. And it is undeniable that a typical business, when confronted with the prospect of labor cost increases, has numerous options. The business can explore ways to improve its productivity. It can raise its prices. It can reduce the salaries of affluent executives, or maybe make a little bit less in profits.**

In the most recent quarter for which financial information is available, August through October of 2014, Staples made $216 million in after-tax profits. Their CEO, Ronald Sargeant, made over $10 million in total compensation in 2013, while other top executives raked in well over $2 million apiece. Barack Obama didn't have those numbers when he was asked about Staples' policy a few days ago, but his suspicion "that [Staples] could well afford to treat their workers favorably and give them some basic financial security" was clearly right on the money. The ACA didn't make Staples cut its employees' part-time hours; instead, Staples management consciously chose to prioritize a fifth car or third house for a few wealthy individuals over its part-time workers' ability to put food on the table. Other large companies, from Starbucks to McDonald's to Walmart, make similar callous choices on a range of issues all the time.

There are two ways to address this problem. The main mechanism currently at our disposal is to loudly call such decision-making what it is -- greedy and unethical -- and vote with our dollars for companies that treat their workers fairly. Opponents of labor standards focus on what businesses will do rather than what they can do in part because we let them avoid moral reckoning. We won't win everyone over, but we must not underestimate the power that moral authority has to shape behavior.

The second mechanism is policy that addresses firms' decision-making. Some recent legislative proposals, in fact, like Congressman Chris Van Hollen's CEO-Employee Fairness Act, have the potential to begin to wade into these sorts of waters. If we're worried that companies will choose to lay people off in response to a minimum wage increase, for example, we could raise taxes on the executives of companies that make this choice.

No matter the policy outcomes, it's critical that we ask the right questions in these debates. It's worthwhile and important to document the evidence that policies like the employer mandate, minimum wage, and paid sick leave have minimal consequences on work. But it's also essential to point out that any consequences these policies do have aren't inevitable.

*As Buzzfeed's original coverage explained, Staples claims that their part-time hours policy has been in effect for over 10 years, and that the memo Buzzfeed obtained only "reiterated the policy." Yet the memo contained phrases like, "Beginning with the week ending 1/4/2014," and "Staples is implementing a policy." A Staples spokesperson did not respond to follow-up questions about the memo's language.

**It's possible, though I've never seen a study to prove it, that some businesses actually can't afford to adequately compensate their workers, that they're barely squeaking by as is with low executive salaries, non-existent profits, and the highest level of productivity they can possibly attain. To the extent these businesses exist -- and I'm skeptical that many of them do -- it's worth asking whether a business's right to keep its doors open should trump its workers' right to make enough to provide for their families. I don't believe it should.

Note: A version of this post first appeared on 34justice.