Broadway saw the birth of a musical legend 50 years ago this week when Lerner and Loewe's Camelot premiered at the Majestic Theatre. But as the overture began on December 3, 1960, the cast and creative team never imagined that Camelot would run 873 performances, closing on January 5, 1963, and achieving mythic status that year as the symbol of John Kennedy's lost presidency. After two discouraging months on the road, the company was grateful to open in New York at all.

The mood that December night was a change from the unalloyed optimism that launched the project in August 1958 when Stone "Bud" Widney put a Times book review on Alan Jay Lerner's desk saying, "Here's your next show!" Lerner, the renowned librettist, quickly ordered a copy of T.H. White's novel, The Once and Future King, because as he wrote in his memoir: "[Bud's] knowledge and experience in the 'steak and potatoes' of putting together a musical is as thorough as anyone I know. But over and above that, he has been invaluable to me when I am writing...He has always understood me well enough to know what I have been searching for."

Flash forward to last week when I call Bud Widney at his home in Spring Valley, New York. He's still active in the theater, and a charming raconteur. When I ask what drew him to T.H. White's quirky retelling of the King Arthur tale, he says, "Instant recognition. I had worked as stage manager for Paint Your Wagon, but my job with Lerner was always to find the next project. Well in '58, My Fair Lady was still on Broadway and he was finishing the movie Gigi, and I was thinking, 'He's written two of the greatest musicals, so where do you go from here?' I felt he needed something that was a 'big idea,' and the hero of the day was Dag Hammarskjöld. When my eyes fell on the review of White's book I thought, 'This is our chance to do a United Nations theme.' What cinched it was the idea that White had taken a witty approach to the Arthurian legend, and I knew Alan would do well with this."

But Widney not only found the novel, he also suggested the show's inspiring finale which later resonated so deeply with JFK. "Alan was in Palm Springs working with Fritz [Frederick Loewe] on the score," Widney says, "and he called me and said, 'This damn show has no ending. It's so tragic, we don't know what to do with it. So can you get out here and remind us of stories in the book that will help us?' I got on a plane and when we met I said, 'There's one story that might have possibilities,' and I mentioned the moment at the end when Arthur meets the little boy, Tom of Warwick, who's supposed to be Thomas Malory. And Alan said, 'Oh my God, that's everything! When we can have the lift of carrying on the meaning of the Round Table, the show will succeed.' He was enormously grateful to me, and I was always proud of that contribution."

When Camelot was announced to the public in March of 1960, its future popularity seemed inevitable. Advance sales grew to $750,000 as three stars were named for leading roles: Richard Burton (King Arthur), Julie Andrews (Guenevere), and Roddy McDowall (Mordred). Two newcomers, Robert Goulet and John Cullum, were hired to make respective debuts as Sir Lancelot and Sir Dinadan, and both would move on to major careers. (Cullum is currently on Broadway in The Scottsboro Boys.)

But despite its glittering cast, Camelot endured many setbacks during its October previews in Toronto. Alan Lerner suffered internal bleeding from a perforated ulcer, and when he left the hospital after a week he learned that Moss Hart, the director and guiding light, had been stricken with a heart attack. Hart's illness was a huge loss since the show was then running four-plus hours instead of the desired two-and-a-half. Lerner needed to cut and refine the book, which some insiders thought was in conflict with itself: the first act was happy, the second act sad. But the librettist also stepped in as director, and as Lerner split his energies, Loewe grew angry and withdrawn. Snarky observers dubbed the show Costalot and "Gotterdammerung without laughs."

In his formal role as assistant to the producers (Lerner, Loewe, and Hart), Widney was concerned about the awful sound at the O'Keefe Centre and Lerner's troubles with the book. But he also felt philosophical. "Every show you do has problems," he says. "That comes with the territory. But you keep working to solve them."

Yet without Hart's guidance, Burton and Goulet grew edgy about their imagined flaws. "Burton was a solid, wonderful actor, but he wasn't a singer," Widney recalls, "so he was a fish out of water. Goulet thought he was inadequate because he was sharing the stage with the greatest actor in the world." He laughs. "The only person who was unperturbed was Julie because she knew who she was and what she was doing and she did it expertly. But they each respected each other for their separate talents."

Alan Lerner could not find a replacement for Hart, so when the show moved to Boston, three pros alternately rehearsed the cast: Lerner, Widney, and Philip Burton, Richard Burton's longtime mentor. "Philip knew nothing about musical theater," Widney remembers, "so if it had to do with the interpretation of a moment for Richard, directing fell to him. If it had to do with staging a musical moment, it fell into my bailiwick. And Alan bridged the gap between the two." While Lerner hacked away at the script, removing scenes and musical numbers, Burton and Andrews buoyed the company's spirits with their charisma and good will. Camelot became sleeker and, by all accounts, more powerful as it finished its Boston run.

One of Widney's fondest memories is the final run-through when the company returned to New York. The production crew began tussling with the scenery at the Majestic, and just before opening the cast rehearsed in an empty theater with a single stage lamp. "Nobody was invited, but I was there with my wife," he says, "and it was the best performance Richard or any of them had ever given. My wife was transfixed. Later she saw the show on Broadway and she thought it was gorgeous, but she said, 'I didn't hear what they were saying until a third of the way into the first act because I was looking at the scenery and costumes so much.' Well, her comment guided me for every production I directed thereafter. The moral is, don't let the costumes and the scenery upstage the story. You need to see the actors, and in the future I got the clutter out of the way which was terribly important."

Camelot received mixed reviews from the New York critics and limped along for the next two months. Word of mouth was poor, and two-hundred people walked out nightly. Mercifully, Moss Hart rejoined the cast in February, and he convinced everyone to resume rehearsals--a step that is seldom taken after a show opens. Hart made stunning improvements, though few people might have seen them if Ed Sullivan hadn't decided to salute the fifth anniversary of My Fair Lady on his TV show (March 19, 1961). Lerner and Loewe convinced Sullivan to present several numbers from the retooled Camelot, and from then on Lerner called that appearance "the miracle."

The next morning there were lines at the box office, and Camelot began its thrilling next chapter. Burton stayed until that fall when he was replaced by William Squire. Andrews left in April 1962, and was replaced by Patricia Bredin, then Janet Pavek, and finally Kathryn Grayson.

The cast recording broke sales records, bringing Lerner and Loewe's music and lyrics into homes across the nation, including the White House. Yet it came as a surprise when, a week after the death of John Kennedy, his grieving widow gave an interview which appeared in the December 6, 1963, issue of LIFE. Mrs. Kennedy said, "All I keep thinking of is this line from a musical comedy. At night before we'd go to sleep, Jack liked to play some records; and the song he loved most came at the very end of this record: 'Don't let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment that was known as Camelot.' There will be great presidents again -- but there'll never be another Camelot."

Reflecting on this unexpected link to history, Widney believes it has greatly helped the show. "It was so tough to make Camelot a hit," he says, "but the musical became one after Jackie Kennedy spoke of it."

Now at the half-century mark, Camelot is usually playing somewhere. Bud Widney has directed many productions including a 2009 version at MUNY in St. Louis. As a respected director, producer, and librettist--you can see his many credits at www.ibdb.com -- he has written the book for a musical about Lerner and Loewe, Almost Like Being in Love, using songs from their shows to illuminate their relationship. Producer Mike Merrick is trying to arrange a national tour. In the recent past, Widney also penned the book and lyrics for a new musical, Hilltop House, working with composer David Christian Azarow. "When we did our reading in the Village last year, we realized it was too long and too big -- so we're bringing it down to size and making it produceable."

Speaking of "produceable," Widney believes the theater has developed "a larger acceptance of what Lerner's book for Camelot was attempting to do." The presence of a happy first act and a tragic second act no longer unsettles audience members who have moved beyond the conventions of the golden-age musicals. "Ultimately," Widney observes, "Camelot speaks about the aspirations of humanity that echo on a large scale. The show is romantic...and timeless."

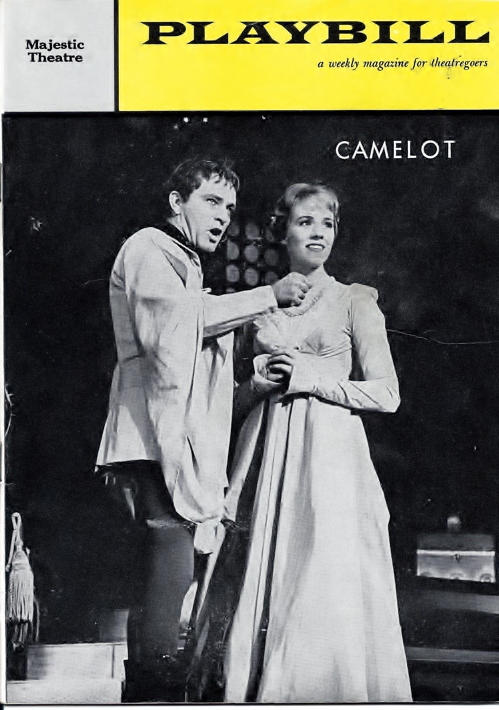

A program from February 20, 1961, featuring Richard Burton and Julie Andrews.

PLAYBILL ® is a registered trademark of Playbill Incorporated, N. Y. C. All rights reserved. Reproduced by permission of the publisher.