Stonemasonry is a craft nearly as old as civilization itself. (More on this here [pdf], here [pdf] and here [pdf].) But is it art?

The craft-versus-art debate is one that has echoed over time. All art certainly requires craftsmanship. But when is craft art? You can find a wide range of opinions on the subject -- for example from here to here, here and here.

And there are those who argue that the distinction is artificial, a product of a cultural bias -- as Margo Jefferson writes in the New York Times, "art for art's sake seems pretty passé."

Stonemasonry is an interesting case in point. There is a lot of craft involved: "quarrying, sawing, shaping, sculpting and fixing natural stone in order to build long-lasting buildings and monuments." But think of all those stones, big and small, stacked together to make a coherent whole -- isn't that art?

Yes, say Hellen Diaz and Mike de Palma (both of New Castle Stoneworks, which sells stone products) in their article "Preserving the declining art of stonemasonry":

“Stonemasonry is one of the earliest crafts in civilization's history. ... Stone installation is an intricate art; the mental aptitude it requires to endure a project for two or three years and turn simple stone into a beautiful and truly unique piece of art is enormous.”

And so did Helen Keller, whose tactile experience of a stone wall led to another kind of art -- a poem titled "The Song of a Stone Wall":

And the days are long. I come and listen;

My hand is upon the stones, and the tale I fain would hear

Is of the men who built the walls,

The Evocation of Geologic Time

Unschooled as I am in the arts, I would go so far as to say that what stonemasons create not only has an artistic sensibility but more specifically an environmental sensibility. Even something as mundane as a stone wall strikes a deep chord in me much as a work of art does. And there's little doubt that some creations from stones are truly awe-inspiring -- and make you wonder if “a spell” is used for balancing.

Consider: each piece of a stone wall comes from the Earth -- each stone's content and shape created by dynamic forces acting over hundreds of millions of years. But not just any stone will do. A human hand must carefully select and place stones to build a structure that can withstand the insults of wind and weather for centuries or more. A work of human imagination that reaches back millions of years and reaches forward a thousand years into the future -- that's pretty remarkable.

I also find that a stonemason's work provides a bittersweet metaphor for life's struggle, a struggle that can take us to great heights but is ultimately doomed to end in death. Just as an organism struggles in vain to survive, to hold fast, cell by cell, in a world being inexorably pulled apart by cosmic, entropic forces, the stonemason seeks to create order and structure using little, random bits of detritus thrown off of the Earth's grandest cyclic process -- the rock cycle.

Each rock is seemingly random in shape and size but is actually hand-picked to connect to its neighbors and hand-placed with the knowledge of friction and gravity to make something that can withstand the test of time. In some cases the works of the stonemason can last centuries (see also here and here) or even millennia [vid] (see also here and here), but ultimately, as the "traveller from an antique land" discovers in "Ozymandias," must give way to the elements.

Thea Alvin: Stone Mason Extraordinaire

Though it is believed to be a dying art, there are any number of wonderful stonemasons who have done or are doing amazing things that speak to us about the environment -- here are a few links to check out and I apologize this is not a comprehensive list: Frederick Law Olmsted (of Central Park fame), Norman Haddow, John Hibbetts, Chris Chiasson. I've recently had the opportunity to meet and speak with one -- Thea Alvin. Indeed it was my meeting and getting to know her that inspired this post.

This extraordinary woman uses her bare hands and a whole lot of muscle and creative energy to build amazing rock structures that curl and twist, undulate in ways that delight and amaze and challenge. Despite having been featured in the New York Times and in Oprah's "O" magazine and having been commissioned around the globe, Alvin lives a rather Spartan life in Vermont with her husband and dog.

I first came across her on a Google search. The Nicholas School was about to embark on constructing a new building and I was hunting for an artist who worked in stone to do a piece for the front landscape. I wanted a stone sculpture because the building's exterior is glass and quite modern looking; I thought that a stone work, something constructed using the stonemason's ancient techniques and composed of the stuff from which glass is derived, would provide an interesting counterpoint and statement about the circularity of life and the cycles that sustain it and the connectedness of all things earthly.

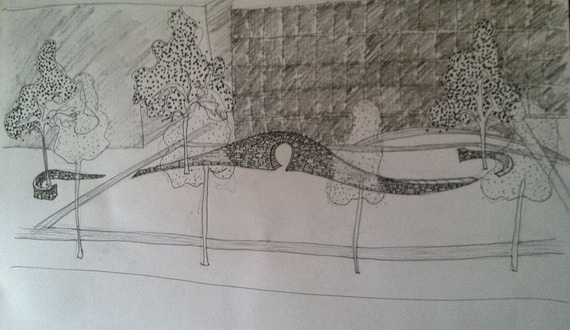

As soon as I found her website and saw her work, I knew she was the one for our project. I contacted her and things fell into place. As I write this, she is working in front of the new Duke Environment Hall constructing "In Good Time." Thea describes her concept for the work as

“a design inherently my own and equally a spokesman for harnessing sustainability through its welcoming flow. This undulating wall will rise and fall as it dances up and down and underground as it wraps trees and dives under sidewalks.”

Playing ‘With the Nature of Physics'*

In describing her creativity, Thea says: "The work I do happens with me, through me and not so much because of me."

Her thoughts on the art-versus-craft debate? She has an interesting take. She sees both craft and art as being essential elements of her work; neither has precedence; they both are critical. And she takes pride in being a craftsman and an artist.

For Thea the craft part is deeply rooted in the age-old techniques of the stonemasons of the 19th century and before, a craft she learned apprenticing for her father in her teens. She uses her muscle and physics rather than machines to move her rocks, and exploits an understanding of the "math of how stones push and pull" rather than employing mortar to place her rocks just so, so they will stay put.

Building stone arches and circles and such requires knowledge of geometrical rules that date back to Roman times. Making sure her stone works can weather the elements requires accounting for the "three rules of water, temperature, and gravity": the rocks selected must be impervious to water or they will burst when temperatures fall below freezing, and gravity can be a stonemason's ally if the rocks are properly placed.

But to Alvin, respecting the craft alone "does not make art." To make art as a stonemason, she says, you must "speak to the stone ... see the beauty in the stone." She clearly sees it as a mystical experience to create a structure that is "perfect in its expression of imperfection."

That's a pretty wonderful metaphor as well -- a metaphor for our world and its inhabitants -- no one single creature is perfect but we're all working together to create a wonderful curling, circling, undulating seemingly perfect thing that we can only hope will survive for many, many millennia.

___________________

End Note

* This and the other quotations are from a seminar Thea gave at the Nicholas School entitled “The Art of Stone.”

Keep up with TheGreenGrok | Find us on Facebook