I read a brief article last week that made me so incensed, I had to put myself into a time-out before I could even finish it. In fact, its title alone -- "'Time-Outs' Are Hurting Your Child" -- had me foaming at the mouth. Then I read the bold print:

In a brain scan, relational pain -- that caused by isolation during punishment -- can look the same as physical abuse. Is alone in the corner the best place for your child?

Wait. What?! Is this why no one should put baby in the corner?

I have serious problems with articles such as this that hyperbolically use neuroscience to influence better parenting (or promote parenting books). Evidence suggests that parental anxiety has increased over the last century as children's roles gradually shifted from laborer and family income contributor to being the family's most vulnerable and precious members. Despite their good intentions, such articles only feed that anxiety. They send the message to already anxious parents that children's brains are so fragile one parental mistake can destine their children to a life of emotional turmoil, low self-esteem, tumultuous relationships, and some debilitating addiction that prevents them from ever being able to hold a job. (Apparently, hyperbole not only generates more anxiety but more hyperbole.)

Interestingly, the authors' statement about relational pain and physical abuse doesn't appear in the actual book, No-Drama Discipline, their article promotes. But here's what the book does say:

In fact, brain imaging studies show that the experience of physical pain and the experience of relational pain, like rejection, look very similar in terms of location of brain activity.

Physical pain? What happened to physical abuse?

There is evidence of a "neural alarm system" in which the circuitry for social pain (as the research literature calls it) and physical pain overlap. In the brain, pain is pain. This means that the same part of the brain (the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dACC) lights up when I stub my toe or when I feel someone is evaluating my dress (a form of social pain). So social pain looks the same as physical pain on an fMRI image. So what? What does this mean for parents? The authors seem to imply that putting my child in a time-out is the same as inflicting her with physical abuse. But that's not what their book states. And it's not what I found in the research. Sure, they qualify their claim by stating that "relational pain...can look the same as physical abuse [emphasis added]," meaning that it doesn't always looks the same. But if one is already anxious about parenting their children, how likely is one to note that qualifier? And how likely are parents to check the claim?

Having worked with anxious parents (and being one myself) in different capacities (first as a therapist and then as a head of school), I could almost hear their questions as I read the Time article: If you're telling me that putting my child in a time-out hurts her brain, then what happens when I drop her off at school or daycare and she cries? Am I harming her brain then? Is it being permanently altered because she thinks I'm rejecting her? The article states that the brain is adaptable, yet it sounds like time-outs could permanently alter it if done repeatedly. But what does "repeatedly" mean? Is using time-out once a day the same as several times a day? Is it the same as once a week? What if I choose to use time-outs because staying with my child while she kicks and screams only seems to incite her more than it does if she does it alone in her room? What's happening to her brain then? And what if I've been using time-outs for five years? Have I damaged her brain and scarred her for life?

Sadly, the book doesn't answer these questions. (In all fairness, however, I should note that I like the book. It's informative and reasonable and not hyperbolic, unlike the article used to scare parents into buying it. But it doesn't cite references, which is a wee bit annoying.)

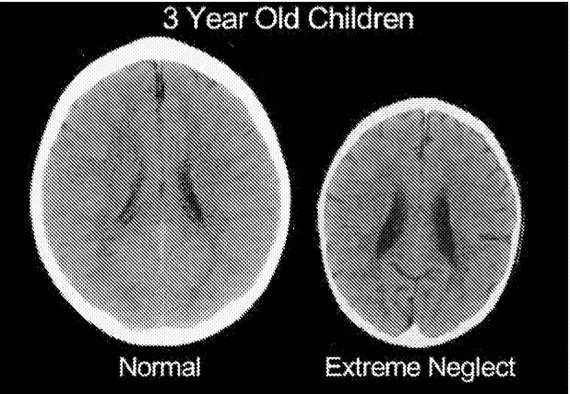

We need to remember that while neuroscience is fascinating, it's still a relatively new field, and it doesn't have all the answers. And those who share its research findings with the rest of the world have a responsibility to do so prudently so as not to misinform or incite unnecessary anxiety -- especially in an already anxious population. I find it irresponsible when, for instance, clinicians use it as Dr. Shelfali Tsabary did in her 2012 TEDx talk. Around minute 5:24 Dr. Tsabary suggests that parents hold "indubitable power" in every seemingly ordinary moment they share with their children. Then she tells us it's not just her opinion but that there is "real science" that demonstrates how our relationships with our children shape their brains. The real science looks like this:

Dr. Tsabary goes on to explain the brain size difference this way:

They differ in the quality of the relationship they shared with their mother. The one on the left [sic] suffered abuse and neglect, and the one on the right [sic] enjoyed a thriving connected relationship. Chances are the one on the left [sic] will grow into an adult at greater risk for drugs, crime, lower IQ, and, most tragically, a diminished capacity for empathy and relatedness.

There is no doubt that extreme neglect will adversely affect brian development, but the key word is "extreme." In the study this image was taken from, we don't know the exact experience of the child on the right, but we do know that some participants "literally were raised in cages in dark rooms for the first years of their lives" (p. 5). Most parents are not raising their children in cages. In fact, my guess is that the people who read parenting books, attend parenting TEDx talks, or even read parenting articles in the Huffington Post are generally NOT the people who are extremely neglectful of their children. But the way Dr. Tsabary has woven this image into her talk, it certainly seems that they might be.

Look, I'm not suggesting that we put baby in the corner, withhold love from our children, or not have awareness around our relationships with them. That would be absurd. What I am suggesting is that scaring parents into being better parents (or buying parenting books) using neuroscience isn't the way to go. In fact, it's likely to generate more anxiety, which can cloud our parenting decisions and keep us from enjoying our children and our parenting experience.

[DISCLOSURE: This author is writing a book for parents about human development so they can be empowered to make informed parenting decisions that are right for their individual families. And she promises not to scare anyone into buying it -- except maybe her own family and friends.]