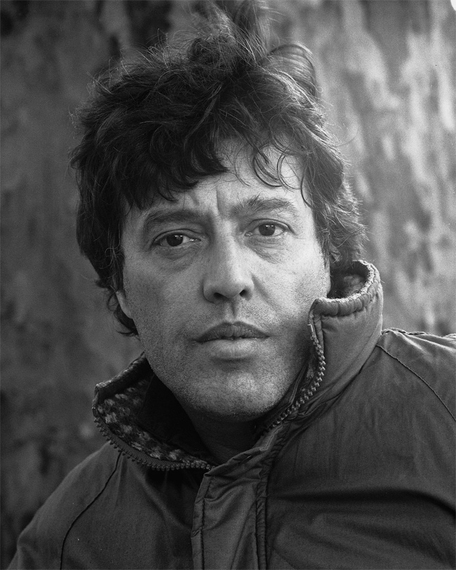

Tom Stoppard. Photograph courtesy of and © Dmitri Kasterine

Stunning literary news came recently of the rediscovery of two lost poems by the Greek poet Sappho. Only shards of details are known about Sappho's life, lived over five centuries B.C.E. on the island of Lesbos in wealth and privilege -- and, consequently, with the leisure time to write poetry. Very little of her verse survives, and what does is personal and passionate, witty and wry, full of intense images and emotion. It's also fragmentary; of some poems, we have only a few broken lines.

Dirk Obbink, on the Classics Faculty at Oxford University, Christ Church College, identified the poems on a papyrus owned by a private collector. They were published in English translations in England and in America immediately after Obbink's discovery was made public. Debate over them, and excitement about them, is great.

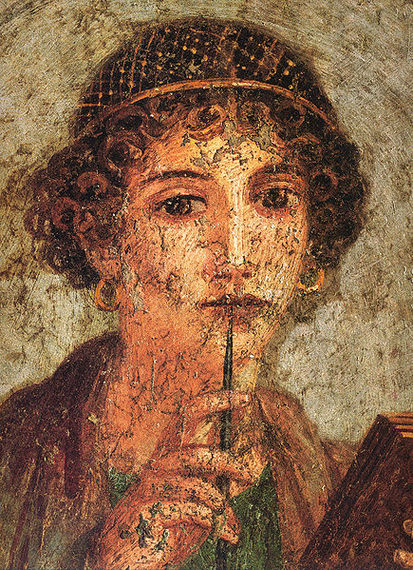

Sappho, in a wall painting at Pompeii

I studied Sappho in college and in graduate school, and have since reread and taught her poems, but their relevance took on new shades to me after I saw Tom Stoppard's play Rock'n'Roll (2006). Stoppard is a writer's playwright; his dramas from the first, though intensely original, have been occupied by and with other people's words. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966) exposes and expands two minor characters from Shakespeare's Hamlet. Travesties (1974) stars James Joyce as a leading actor, and focuses on a production of, while metatheatrically also containing, Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest. Stoppard used Wilde again in The Invention of Love (1997), though the central literary figure appearing there is A.E. Housman. My favorite use Stoppard makes of a writer is Lord Byron, the absent presence of what is to my mind Stoppard's best play, so far: Arcadia (1993). Sappho is the writer who -- in the rather unlikely but very felicitous company of Vaclav Havel, Bob Dylan, the Plastic People of the Universe, The Beach Boys, The Rolling Stones, and, principally, Syd Barrett -- recurs and stirs and furthers the intricate thirty-plus-year story of Rock'n'Roll.

Eleanor, the Cambridge classicist dying of cancer when we meet her in Rock'n'Roll, specializes in Sappho's poetry. In the very funny scene of her first tutorial with an earnest graduate student, sometime in late 1968, the two discuss Fragment 130, as Eleanor calls it "Eros the knee-trembler." What engages Eleanor about Eros is that he "is amachanon, he's spirit as opposed to machinery...He's not naughty, he's -- what? Uncontrollable. Uncageable." The lacuna, where part of the text is missing on the original papyrus, matters less to her than this powerful invention of love.

The second tutorial, with another student and closer to Eleanor's death, is not funny at all. We see her fear, and her putting on her wig before the meeting. Lenka, the student, is less interested in the poetry than in Max, Eleanor's "bruiser" of an intellectual husband. The poem they discuss is one of the most complete, He seems to me equal to the gods. Lenka's breathless close-reading of the poem billows with life, and politics. Sappho felt love as a symptom, says Lenka: "There are some among us who think knowledge is advanced when we give something a new name. Goodbye, Eros; hello, libido. Goodbye, Muses; hello, inspiration." Eleanor tries to posit Eros and Aphrodite as a metaphor, but Lenka won't have it: "Sappho didn't know why things fell to the floor. So what? They fell anyway. She looks down the table and she is in love separate from her body. (She plays her trump.) If it's an illusion, who's having it?" The intellectual postures of the tutorial give way to physical fact and emotion in the end, as Eleanor "pleasantly" tells Lenka, when they are alone, not to "try to shag my husband till I'm dead." Lenka won't be teaching Sappho, in this play: as it concludes, she teaches her own student the historian, Plutarch, and the lines from his Moralia (The Obsolescence of Oracles) about the death of the great god Pan -- the rustic god of nature, music, and sex, among other things.

Yet the great god Pan is not dead. Poetry prevails over politics and intellect and academia and national borders in the end. The music of the banned, persecuted Czech band the Plastic People plays in Prague cafes by 1990, and the Rolling Stones stage a concert there for over 100,000 people -- including Stoppard's dimly autobiographical hero, Jan (whose name was Tomas in the play's first draft) and the still-radiant flower child Esme, the two together at last, and perhaps always having been in love.

As I read the two new Sappho poems for the first time, I thought of Stoppard constantly. It seemed as if he'd somehow conjured them into re-existing, to me at least, by the graceful, gracious way he treated Sappho in his most recent stage play. What would it be like for him to read the poems, I wondered. Without Rock'n'Roll, I would not have gasped to see the new-broken news of Sappho. Stoppard's own ability and agility in making the past present is what also makes him my favorite playwright in English since Shakespeare, whose fluid unfixable time in plays like Hamlet and Twelfth Night is one of their most magical features. What most matters, though, in Hamlet's phrase, are words, words, words. Writers who love words, and use them with passion and purpose and poetry, have kinships that trump time.

© Anne Margaret Daniel 2014