When I think back on my first impressions of Malawi, Africa, setting foot in the country as a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer in 2007, I always come back to the bus ride from the airport to our training center; along the side of the road I saw coffin making shop after coffin making shop, with the wooden boxes laid out in all sizes, most notably the child-sized varieties. It was then that I was overcome with the impact AIDS, malnutrition and other diseases were having on this country.

I took in Malawi with my eyes, my nose, my mouth, my hands and my ears:

Stepping foot into the capital of Lilongwe, one is accosted by a variety of smells, burning garbage and body odor being two of the most evident. Not exactly pleasant, but a true sense of the country nonetheless. Without a proper disposal system, if the garbage isn't burned, it's buried; if it's not buried, it's burned. Walking into the local grocery store, it is easy to understand why body odor is always hovering in the air -- deodorant is one of the most expensive items in the store.

When you get down to the village level your senses really erupt. There is the cow, goat and pig dung that is used as fertilizer for kitchen gardens, not to mention the faint aroma of dog urine in the air. But, beyond these stenches there is the smell of culinary staples almost constantly being cooked over fires: nsima, the Malawian delicacy, made from ground maize and water, and stirred until it's a sticky patty; mustard leaf and spinach with salt; goat and chicken meat boiling in a sauce of tomatoes and onions.

Better than smelling the family dinner is tasting and one cannot taste a Malawian meal without feeling it as well. You take a palmful of nsima and you roll it around until it becomes a plump ball in your fist. You then use it to scoop up some of your relish -- the spinach and maybe some beans or meat. The blandness of the nsima is masked by the saltiness of the greens, the mushy texture of the beans and the tenderness of the meat.

The sounds of the village come next. The wails of hungry babies mix with the cackles of small children, wheeling rubber tires with sticks. The goats' bleats, the roosters' mating calls and the cattle lowing cause your ear drums to vibrate. If you are close enough to the waterhole, you can hear the chatter of the amayis (mothers) gossiping while they slap their wet clothing against rocks. Off in the distance by the school-house there is an impromptu choir singing, "Edzi! Edzi!" -- a song teaching the prevention methods against AIDS. And just beyond there, young men yell to one another as a goal is scored in a football match.

Post-training, once I was stationed in a village in the center of the country, I began to learn more about the traditions and cultural staples in Malawi that shocked me beyond anything I had heard of before. For instance, the idea of "wife inheritance" - wherein a widow is inherited by her deceased husband's brother or another male of the family, regardless of whether the man already has a wife. The puberty rites that many children in the village experience sounded like sexual assault to me, an older man or woman deflowering them when they are deemed to have come of age.

While I knew that the term "feminism" did not exist there and the idea of "women's rights" was being played out in a debate of whether female genital mutilation was a cultural need or a human atrocity, I had been unprepared for just how much I would have to bite my tongue when these issues came before me in the field.

My time in Malawi instilled in me so many memories and teachings that I never would have been privy to otherwise. I learned much about myself and aid organizations like the Peace Corps as well, all of which has led me to flesh out my thoughts and put them down on paper in the form of a novel.

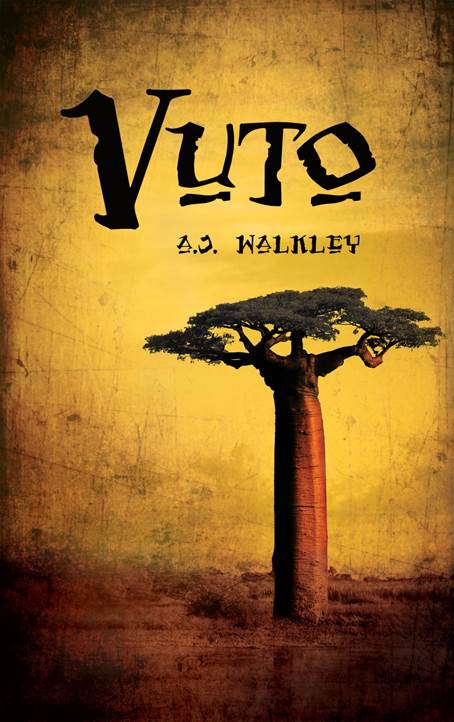

I wrote the book Vuto (which means "trouble" or "problem" in the Malawian language of Chichewa) to not only get across some of the cultural aspects that were so foreign to me as a white United States volunteer with little knowledge of Malawi and Africa, but also to show how unprepared newly graduated volunteers can be going into a Third World country thinking they can make a difference. It is my hope that readers will learn a little more about cultures foreign to their own, as well as the world of volunteers by picking up Vuto.

Vuto will be released on July 22, 2013