In a report released last Friday, Human Rights Watch criticized the Congolese judicial system's continued failure to protect the victims of rape and sexual violence in the country. In a recent trial where 39 soldiers were charged with the mass rape of almost 80 women and girls, just two were convicted.

HRW offers recommendations to address the problem, strengthening DRC's judicial systems to prosecute military perpetrators. Celebrity advocate Angelina Jolie and former British Foreign Secretary William Hague have championed similar policy solutions.

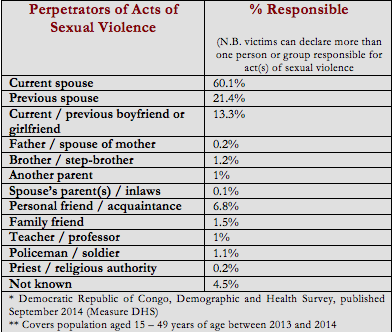

But, this obscures the fact that soldiers are in fact responsible for just 1 percent of reported acts of sexual violence in the DRC.

Congo analyst Jason Stearns backs this up, remarking that "rape by soldiers and combatants is certainly the most brutal and gruesome. But it is not the most prevalent [in Congo], not by a long stretch."

By contrast, DRC's recently published Demographic and Health Survey highlights that more than 80 percent of the victims of sexual violence identified a current or previous partner as the perpetrator.

The survey also highlighted that the least stable regions of Congo were not the worst affected by sexual violence and rape. In North Kivu, the very epicenter of much of the fighting, 27 percent of women were exposed to sexual violence between 2013 and 2014. The comparatively peaceful provinces of Bandundu and Kasaï-Occidental saw even higher prevalence rates of 31 percent and 36 percent respectively.

Even in the minority of cases where soldiers are responsible, experts doubt the effectiveness of prosecution as a preventative strategy in a country where 48 women are raped every hour. As Harvard Professor Dara Kay Cohen has argued, "It is not at all clear that prosecuting perpetrators of wartime rape serves as a deterrent for the future perpetrators of the same crime."

Cohen finds that rape -- and mass rape in particular -- is principally committed not as "weapon of war," but rather as a gruesome means to strengthen the social bond among troops. The immense internal pressure exacted on combatants to participate in this means of socialization vastly outweighs any potential deterrent effect of the fear of prosecution.

While we know that combatants are responsible for just a tiny fraction of acts of rape in DRC, much more can be done to prevent this specific form of violence. Research has highlighted the defining role that senior commanders have played in a number of conflicts in setting and enforcing intra-group norms that strictly forbid rape.

Emmanuel Kabengele, one of Congo's leading authority on security sector reform (SSR), believes that this is also the case in DRC: "This isn't just a technical problem. It's also about leadership and management within the armed forces."

Investments in SSR programming in Congo should target senior commanders and generals in the Congolese armed forces to begin to institutionalize these norms.

But as a first and urgent priority, policy interventions must challenge harmful constructions of masculinity -- what it means to "be a man" in Congo. Researchers at a leading hospital in DRC have documented the rise of "failed, dysfunctional and violent masculinities" linked to men's restricted capacity to provide for their families during economic decline and conflict.

Programs must focus on defining sexual consent within a relationship or marriage in DRC, particularly in rural areas where these cultural norms are most pervasive. Local and national elections scheduled within the next twelve months in DRC provide an opportunity for a national conversation about intimate partner rape.

Finally, the Government of DRC and international donors must make a concerted effort to tackle this problem in the marginalized western and central provinces. The eastern provinces of North and South Kivu continue to receive the vast majority of funding and attention. Rape and sexual violence is a problem faced by communities across the country. The policy response must similarly be nationwide in scope.

Congo has suffered from its singular framing as "the rape capital of the world."The attention devoted to this problem has inadvertently led to the neglect of other opportunities and challenges in DRC. It has also led to a fundamental misunderstanding of the causes, consequences and solutions to sexual violence. Armed with reliable data on who is responsible for rape, why it happens and where it happens, we must develop better preventative measures.