Year One, 2010. Oil on panel, 24 x 30 in.

I first saw Echo Eggebrecht's work at Horton Gallery in Chelsea, in a solo show titled "Spells, Spoils & Lucky Charms". Her lucky charms were in the form of paintings -- seven small paintings that fit perfectly to the cozy space. The work felt so expansive -- with regards to style, influence, narrative, the interiors depicted -- but localized all the same, capturing moments, indefinable but intriguing, solemn but also exuberant. Her painstaking technique and attention to detail, as well as use of color, was surprising coming from a young painter. I'm looking forward to following Eggebrecht as her practice evolves.

Eggebrecht (b. 1977, Bangor, ME) lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. She received a MFA from Hunter College and a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She has had residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, NE. Her work has been included in solo exhibitions at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York and Ter Caemer Meert Contemporary, Kortijk, Belgium.

I conducted this interview with Echo in late September in her studio in Brooklyn. She had just moved back into her studio after a residency at Triangle Arts Association in DUMBO, Brooklyn.

MC: I saw your show at Horton Gallery, and I think your work is beautiful.

EE: Oh thank you.

MC: There's a folksy quality to your paintings--I'm sure you hear that a lot.

EE: Yeah I do hear that a lot, which is weird for me because I've been in art school since I was 15. But I can kind of see it in a way that when I get into the studio, I sort of go into, it's not autopilot, but I'm definitely making work that I'm interested in making...

MC: By 'folksy' I don't mean lack of sophistication or work not informed by art history. In fact, the opposite -- I feel like there's a real sophistication to the work. I even sense a relationship more to early Netherlandish painting than American folk art.

EE: Yeah, I love the Flemish primitives, and that kind of work. The spatial history behind painting is so dense and so specific that once you get interested in something that odd, in terms of a moment in time, when that spatial history is being so defined and so visible it's so iconic. Then I think it definitely comes out. I have more of an interest in that stuff than I actually do in American folk art, which I love, I just don't know as much about it.

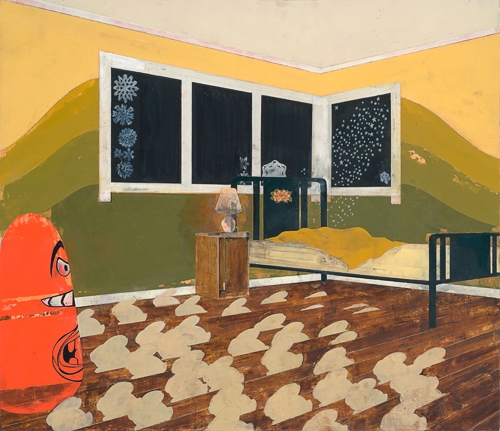

Stopwatch, 2008. Oil on panel, 20 x 24 in.

MC: Can you talk about a little bit about your approach to painting -- when you have the blank canvas in the studio. Where do the images come from? Do you draw from something physical or just from memory?

EE: Um...I do all of it. I find Google images...I mean, I'm sure that this is true for every single painter, but I find it frustrating, and it's something that you want to do because it seems so easy, but at the end of the day it becomes so much more complex than figuring it out in a three dimensional way. So I tend to make models still, and I bring things into the studio and manipulate them and then paint that way. The image becomes clearer if I go into that space where I need to pull from the photograph; I am always making some kind of compromise. There are so few elements to my paintings and the relationship between those elements for me is everything, so to compromise one of those is kind of too big of a deal.

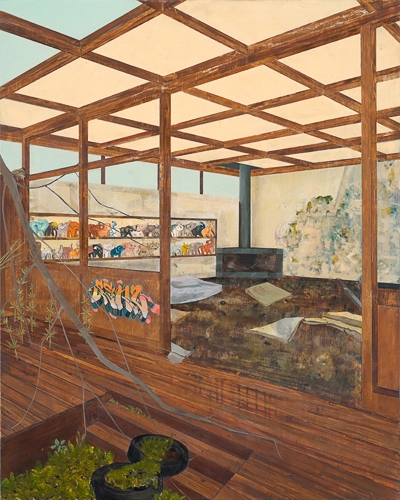

Building A Desert, 2010. Oil on panel, 25 x 29 in.

MC: And can you talk a little bit about color and your approach when creating a palette.

EE: I'm obsessed with color, I think about color all of the time. And I build palettes, and those palettes definitely shift in the making of the painting, but I do like to lay out a couple of like...two or three colors and build a relationship. I mean I'm always looking at colors, especially in film. I'll walk away from a film and try to remember exactly when that scene came up, and look it up later. I definitely make a palette. I'll try to store paint in jars and then go back in. But it always ends up being like combinations of things.

MC: In the series I saw in the "Spells" show, there were a lot of muted colors and earth tones.

EE: Those paintings definitely have a very strong color relationship, and I definitely did that intentionally. I built all seven paintings at one time instead of going painting by painting, which is more typical for me. I've learned so much in that process, having all that intensity or that relationship broken up seven ways instead of finishing something and moving on. I wanted to do that in a way to see if I could create something in seven parts and think of it as one total installation instead of thinking of it in terms of each painting. I see it as kind of a room of paintings.

MC: Yes, the paintings speak to each other even though there's no apparent running narrative. That's how I felt when I was in the room. And it seemed like the perfect size room.

EE: Oh I know I love that space for the work. I was in a bigger gallery before and I blew the paintings up to fit the size of the room and it ended up killing my relationship to the work in a lot of different ways... so yeah, the space is great. It was a really intense show for me in a way that I did learn a lot from doing it, but I was also constantly moving [studios] with the paintings. I would pack them up, ship them, reopen them, look at them. Usually I'm just working in this space, so the way that I saw that it changed when I was in all of these different rooms with all these different areas was just kind of weird.

Eggebrecht's studio

MC: How would you define your practice at this point in your career?

EE: Okay. Well I think my practice is in a real state of flux at the moment. I'm going back to making a lot more drawings, which I never did before. I've always tried to draw because I love drawing so much, and in my opinion the most beautiful art form. I'll always gravitate towards drawing shows... just how fresh it is, and you know, how it's its own thing. But, I've always had a hard time thinking with that kind of vocabulary because my paintings are so labor intensive and I need to sit with them for so long. And the idea of doing something for like an hour or two didn't make much sense. So I'm going back and starting to draw more, and I'm working with different materials. I'm just sketching that out in acrylic, and I'm thinking of it as a drawing as well before I go in and start painting with it. So, I feel like the surface of the paintings will change a lot, which I'm excited about. I'm excited about pushing myself to try and make them as fresh as possible, and decide to work things at different scales, essentially, in terms of detail.

MC: And what is your everyday? Do you have a routine or do you go day to day?

EE: I'm incredibly structured. And that happened actually through the [Horton] show. That was one of the most difficult things for me to figure out. I think that working for yourself especially, and any kind of artist I feel like when do you stop? It's so difficult to figure that out. So if I wasn't working, I would feel guilty, and then I would try to avoid working because I felt like I needed a break, but then I'd be sitting there trying to do something else, but I'd be unable to. Being a writer is exactly the same I'm sure. So I would wake up at 7 am and then I drew for three hours, I worked on one painting for five hours, and then I worked on another painting for five hours, and that was it. And it really changed the way I painted, it changed the way I thought about the paintings.

MC: That's a pretty long day!

EE: It was a pretty long day, but it was also a shorter day, because I would wake up and I would typically work on like one painting that day. If you're sleeping for 7 hours, you know, you have that entire time left. So, for me, it was like, if you work in these five hour increments I was having to make decisions, instead of doing something that was sort of...you know?

MC: It sets up a structure. You give yourself goals to reach in each increment.

EE: I would literally set a timer and then it rang and then I'd have to finish.

MC: So, now, after the show have you continued with this schedule?

EE: Yeah. I'm also working on this small painting and a big painting. Even having those scale shifts in size has made a huge difference for me because this will be finished much faster than that. So that can rotate. So, there's like an influx of new work that comes in while I'm working on a larger piece, but it's still in those parameters of me getting that done.

MC: Is there some sort of running narrative, or a narrative in each of the works, or through the series of works?

I'm definitely an avid reader, and I think the paintings are textual--I think that they come from a relationship between, or they're built from buildings of moving from one text to another text. There is almost a formula to my own behavior where I'll start working on a show and it's very research based. I always start a show when the last show I did is up, so there is no pressure to be making something. So I spend a lot of time reading, and then it starts to piggyback, and you can sort of follow it as a train of thought.

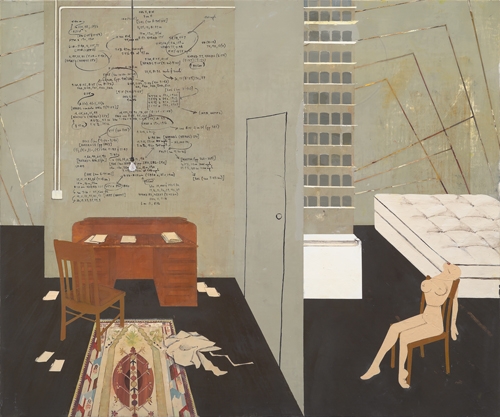

Painting For Don Delillo, 2008. Oil on panel, 20 x 24 in.

MC: Are you reading The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay [referring to the book by Michael Chabon sitting on the artist's table]?

EE: A lot of that is just coming out of the last show, when I read a lot about magic. And so that book I had bought during that period, and I just always wanted to read it. It got pushed to the side because I was having a hard time getting into it because I was reading mostly non-fiction. This time I picked it up and I can't put it down. It's just one of those books.

MC: It's interesting that you say books and film inform your work because I feel as if there's sense some sort of underlying narrative or running story in your work as a whole or your practice. But your work also exists outside of any narrative. You leave it open for the viewer to create his or her our own narrative or not. But I found myself looking at your work and asking myself Where is this room? or developing stories around particular references you've included, or sometimes just admiring elements of pattern or colors.

EE: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense to me, in a way that I kind of do the same thing. And that's where they get from one point to another point. There are definitely moments of narrative within the paintings, I guess is a better way of saying it, and those moments are not linear, and they are definitely moments instead of being... I definitely think that there are these things that have made an impression on you, and they work themselves back to you in these different ways, and sort of re-contextualize themselves.

Milk, 2008. Oil on panel, 20 x 24 in.

MC: But there are aspects of your work that are more abstract than representational as well--certain shapes and patterns, but not necessarily context, that also weaves into the work.

EE: It's weird, I definitely love paint, and I love working with it as a material, the materiality of it, but what's strange about the kind of painting I like--I definitely love a lot of really old art, like Botticelli and Breugel and those kind of guys. But the paintings that I look at now when I walk around Chelsea, the stuff that I gravitate towards is abstract painting. And most of my best female friends make these beautiful abstract paintings. I don't know what it is, if it's a break from that puzzle, and it's just a formal examination of something for me, or if it's like a visceral thing.

MC: There's just something indescribable about it. It affects you in a different way. It is that sort of visceral attraction. And it could take place in a more concrete narrative work, or even figurative, but there are always these elements. When you see these abstract elements combined with representational forms, it offers some sort of accessibility to the work. Because I think abstract work can really turn some viewers away because they're afraid that they're supposed to understand something, but it's not about that.

EE: Well for me I think that my studio practice, and my brain, is always a 24/7 thing. There are not a lot of lines between...even though I did find the structure, it is still a way for me to find out what it all means and how I'm going to get inside of this thing and put it back together. It is a puzzle for me. I think that's why I like abstract painting so much because there is a negation of that kind of self-consciousness, or that cognitive overdrive, whatever you want to call it.

MC: I think that's the power of art, really. You just can tap into in on so many levels, and there's always that kind of puzzle. That's how I see it--you just want to start to unravel it, and you never can fully. If you talk to the artist you have a deeper understanding perhaps, but still, the work will exist outside of the artist once it's completed. And there's something beautiful about the process too, of course. There are works that are definitely more process-based, but painting must be so difficult. There is so much historical weight to painting, it's got such a rich history, and you're trying to make things fresh, and it's hard but you make it fresh in your own way.

EE: I think, too, if you make paintings, you have a tendency to really love painting. So it's kind of a weight. But it's also kind of like porn, I mean it's everywhere. You can just start new paintings all the time.

MC: I've been seeing a lot of painting shows this year, which has been wonderful. A few months ago, I saw the Alice Neel show in London and, well, just thinking of her work as well -- there is very much a figurative and narrative element to the work, but there is also an element of abstraction in the composition, the shapes and patterns.

EE: Yeah, definitely in the compositions.

MC: ...the entire composition, how it all works together--the figures, shapes, patterns, and marrying those and making them work. I guess I shouldn't say this being a writer and all, but there is something indescribable about particular works.

EE: I love that, though. I saw David Foster Wallace at the New Yorker festival about ten years ago -- and I love books, I would definitely say it's my first love. He was saying that he writes and he looks to authors... what he's looking to find in any novel is this moment when someone explains something that he had felt but never been able to self-articulate. For him it's a moment of growing self-awareness and self-connectedness. I feel like that with art, but for me, it's more powerful somehow, because it's being visually articulated, so it doesn't have a language, which is weird.

MC: Again, it's like that moment when something unlocks, and it's like [sigh]

EE: Definitely. It feel likes you've been punched in the stomach.

MC: Yes.

EE: It's almost like you can't look at it. I don't know, I mean I get shy around it or something.

MC: Marina Abramovic said, 'A good work of art is when you can feel it when your back is turned to it'. You just feel it there. And I agree, you just sense it.

EE: Yeah definitely. Kubrick is my favorite directors, and Jump Cut from 2001 had such a lasting power for me that I'll be experiencing something totally different and totally unrelated to that in every way, and it just connects to that feeling, and brings that back. That's kind of another version of having your back to something. When those moments happen it's like... I don't know... you're really living with this thing.