The central exploration of our three-hour PBS documentary "Superheroes: A Never-Ending Battle" (and its copious companion volume, published by Crown) is how did costumed comic book adventurers smash through the walls of American culture and come to our rescue. But, perhaps, an equally intriguing exploit would be to examine how American history made its way into superhero comic books.

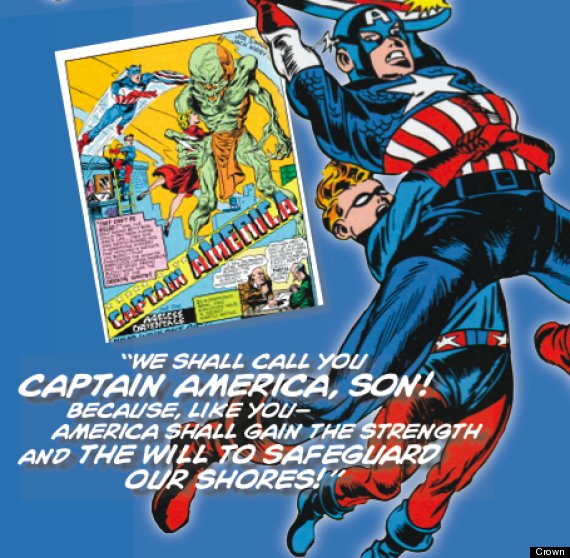

From the very beginning--which is to say, "Action Comics #1," Superman's debut issue in the spring of 1938--an early, scrappy version of Superman wrangles a confession out of a crooked D.C. lobbyist by dangling him over the dome of the Capitol building. (Whether or not such a method might make Ted Cruz behave is anyone's guess.) As America began its ambivalent march to war in 1940, a star-spangled hero burst forth to defend his country: the Shield, who works for the FBI and whose secret identity was known only to J. Edgar Hoover (whether or not Hoover secretly pined to try on the Shield's costume is also anyone's guess). Several months later, the more celebrated Captain America emerged to sock Hitler on the jaw on the cover of his debut title; inside, a discreetly-rendered President Franklin D. Roosevelt approves of the Super-Soldier experiment that created Cap--the first appearance of a president in comic books.

With the United States' entrance into global conflict on December 8, 1941, the red, blue, yellow, and green gloves were off. Superheroes and superheroines of all stripes (and stars) exploded to fight the Axis powers and hardly a month went by without Hitler, Tojo, Mussolini, or some real-life senior brass from the U.S. Army appearing in the 64-page color comic books. When the war came to an end, however, superheroes almost entirely vanished from the comic book universe (save such heavy-hitters as Superman and Batman). As author Michael Chabon put it in our series: "A lot of GIs who came back from the war weren't so willing to keep reading comic books about guys wearing tights and driving Batmobiles. For someone who's fought in a war, that it doesn't coincide quite with the reality of fighting evil." During the Truman and Eisenhower administrations, real-life political figures barely figured in comic books; they were too busy persecuting comic book publishers for perceived threats to American youth. (In 1954, a Senate subcommittee looked into comics as the roots of juvenile delinquency.)

By the time John F. Kennedy was elected, however, a new generation of superheroes had emerged and Kennedy seemed like the sort of fellow who might be welcoming to a jaunty costumed adventurer. Superman's editor, Mort Weisinger adored Kennedy and who worked out a cross-promotion with the White House in which Superman would endorse physical fitness for kids on behalf of the Kennedy Administration. (At one point, Superman even confessed his secret identity to J.F.K., saying, "If you can't trust the President of the United States, who can you trust?") Perhaps it was mere coincidence, but in the months following Kennedy's assassination, Marvel Comics resurrected its wartime champion, Captain America--passing the torch, indeed.

Lyndon Johnson didn't get much serious play in comic books (although in the 1966 Batman movie, he is heard on a phone call--voiced by Green Hornet actor Van Williams, a fellow Texan); there was a one-shot 1967 parody called The Great Society Comic Book, where "SuperLBJ" got enmeshed with costumed versions of the Kennedy brothers--"Bobman and Teddy." By the early 1970s, few of the young scribes writing comic books would have considered Richard Nixon a president they could trust. In fact, Nixon appeared as a villainous foil in two seminal comic books: the first was a 1974 storyline in Captain America and the Falcon where Cap learns that the fiendish mastermind behind the anarchic Secret Empire is actually the President (subtly, but obviously, revealed to be Nixon, who shoots himself rather than be exposed to scandal and Cap is so disillusioned that he gives up his public identity and becomes Nomad, a hero without a country); the second was Nixon's ongoing role in Alan Moore's 1986 Watchmen, as an aging and eternal president. The provocative comic book writer Steve Gerber nominated his creation Howard the Duck to run against Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford in 1976; ten years later, Frank Miller presented Ronald Reagan as a mummified cowboy in "The Dark Night Returns."

A more respectful approach to the nation's highest leader returned in "Superman: The Man of Steel #20" when Bill Clinton (and Hillary) stepped forward to eulogize Superman after his temporary but well-publicized demise in 1991. The 9/11 tragedy resulted in a sea-change among superheroes--the "grim-and-gritty" vigilantes of the 1990s receded somewhat, in favor of more optimistic heroes, without the pathological underpinnings. And, in keeping with this more tempered approach to heroes and patriotism in the post 9/11 environment, George W. Bush was portrayed as a thoughtful leader in Marvel's 2006 Civil War saga, which, in the shadow of the Patriot Act, questioned whether superheroes should be entitled to greater civil liberties than the average citizen.

Whether or not comic book creators were particular fans of any one President, there had never been a President who was an outspoken fan of comic books until candidate Barack Obama stepped forward in an Entertainment Weekly interview in 2008. When asked about comic books (apparently, he was a collector as a kid), Obama opined: "I was always into the Spider-Man/Batman model... they have some inner turmoil. They get knocked around a little bit." Comic book fans around the country went berserk with the happiness of conferred recognition. Marvel Comics, seizing an opportunity, elbowed DC Comics out the receiving line with "The Amazing Spider-Man #583," which featured a short introductory story that had Peter Parker covering the Inauguration of Obama in Washington. Versions of that issue sold more than 350,000 copies--roughly five times what a typical Spider-Man comic sold at the time.

Americans of all ages have enjoyed superheroes since the Great Depression and marveled at their superpowers: the ability to leap tall buildings, burst into flame, wield razor-sharp claws, toss mythical hammers, and so on. Yet, so far, there has been no superhero with the ability to break Congressional gridlock; that, clearly, is a power far beyond even immortal men (and women).